In this post, I set out and explain some of my criticisms of Ha-Joon Chang’s book, Economics: The User’s Guide.

First off, a caveat: I am not an economist. Although I’ve done a couple of undergraduate economics courses and have a strong interest in the subject, I don’t have an economics degree. That said, I still feel qualified to criticise this book as Chang himself says that economics should not be the exclusive domain of professionals, and encourages non-economists to engage with the subject. Furthermore, the book is aimed at novices and Chang’s points are generally simple ones, so you don’t need to be an expert to push back on many of them.

My main, high-level criticism of the book is that it has a strong bias. One way that bias manifests is in the way Chang frequently misrepresented his opponents’ arguments. There are also a couple of areas where Chang’s arguments are rather weak, because he’s overlooked an important fact or jumped to conclusions too hastily. I give examples of these below.

The examples I list here are those that I found dubious based on my existing knowledge. There may be other inaccuracies I have overlooked — if you’ve read the book and found some, please share in the comments below.

General bias

Everyone has their own biases; we’re all human. I don’t begrudge Chang for having his own views, and holding them strongly. Actually, I found it refreshing to hear many of his heterodox views on economics. Too often, those who criticise economists don’t really understand the economic theory themselves and struggle to explain why an economic theory is wrong.

However, Chang’s bias pervades the book and leads him to make some of the mistakes I discuss below. And while a couple of Chang’s critiques of conventional economics might be valid, most of his criticisms are well-trodden (even back in 2014) and there are counterarguments to them. Unfortunately, when Chang states his views, he usually fails to explain why mainstream economists may disagree with him, leaving you with the (false) impression that mainstream economists have simply never considered his arguments.

If this book had been called something similar to “23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism” (Chang’s earlier book), I may not have minded the general slant of the book. But if you’re going to call yourself “the user’s guide”, I’m going to hold you to a higher standard of objectivity.

Misrepresenting opponents’ positions

Chang frequently misrepresented or “straw-manned” his opponents’ positions, making them look weaker than they actually are. While oversimplification is somewhat inevitable in a book that tries to summarise the field of economics in roughly 400 pages, Chang’s propensity to oversimplify seemed stronger when he described positions he disagreed with.

Some examples involve:

- the logic of supply-side economics;

- Chang’s portrayal of the Austrian and Neoclassical schools; and

- the Efficient Markets Hypothesis and rationality.

The logic of supply-side economics is not contradictory (though it may still be wrong)

In discussing the Reagan tax and welfare cuts in the 1980s and the so-called “trickle-down theory”, Chang writes:

The Reagan government aggressively cut the higher income tax rates, explaining that these cuts would give the rich greater incentives to invest and create wealth, as they could keep more of the fruits of their investments. Once they created more wealth, it was argued, the rich would spend more, creating more jobs and incomes for everyone else; this is known as the trickle-down theory. At the same time, subsidies to the poor (especially in housing) were cut and the minimum wage frozen so that they had a greater incentive to work harder.

When you think about it, this was a curious logic — why do we need to make the rich richer to make them work harder but make the poor poorer for the same purpose? Curious or not, this logic, known as supply-side economics, became the foundational belief of economic policy for the next three decades in the US — and beyond.

This comparison between income tax cuts and welfare cuts is not fair. Income taxes create different incentives from welfare benefits, so cutting income tax rates will have different incentive effects than cutting benefits. Taxes on (labour) income are based on work — the more you work, the more tax you pay. In contrast, benefits are inversely based on income/work — the more you earn/work, the lower your benefits. So it’s easy to see why cutting taxes and cutting benefits might both incentivise work.

Now, exactly how strong these incentive effects are is very much debatable. Incomes are only partially responsive to changes in tax rates and the level of responsiveness depends on many factors (e.g. type of income and what the actual tax rates are). There’s certainly evidence to show that supply-side proponents’ claims that cutting taxes will always (or most of the time) increase tax revenues are wildly over-optimistic. I’m not trying to argue in favour of supply-side economics here — in fact, I think the arguments are usually wrong. But, contrary to Chang’s suggestion, there’s no contradiction in the underlying logic.

Unfair portrayal of Austrian and Neoclassical schools

Chang evidently supports a high degree of government intervention in the economy. He appears to dislike the Austrian and Neoclassical schools, which are both sceptical of government intervention. Unfortunately, his dislike for those schools comes through in his descriptions of them.

Austrian school

Chang characterises the Austrian school as believing that:

… any government intervention other than the provision of law and order, especially protection of private property, will launch the society on to a slippery slope down to socialism — a view most explicitly advanced in Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom. (Emphasis added.)

I haven’t read The Road to Serfdom, but the above quote sounded so extreme that I had to look it up. From the condensed Reader’s Digest version, I found that Hayek recognised a far broader role for government than merely providing law and order (at page 46):

The successful use of competition does not preclude some types of government interference. For instance, to limit working hours, to require certain sanitary arrangements, to provide an extensive system of social services is fully compatible with the preservation of competition. There are, too, certain fields where the system of competition is impracticable. For example, the harmful effects of deforestation or of the smoke of factories cannot be confined to the owner of the property in question. …

To create conditions in which competition will be as effective as possible, to prevent fraud and deception, to break up monopolies – these tasks provide a wide and unquestioned field for state activity.

Hayek even accepted the government should provide a minimum safety net (at pages 66-67):

There is no reason why, in a society which has reached the general level of wealth ours has, the first kind of security [the certainty of a minimum sustenance for all] should not be guaranteed to all without endangering general freedom; that is: some minimum of food, shelter and clothing, sufficient to preserve health. Nor is there any reason why the state should not help to organize a comprehensive system of social insurance in providing for those common hazards of life against which few can make adequate provision.

So it’s wrong to say that the Austrian school — and The Road to Serfdom in particular — did not support any government intervention beyond law and order.

Neoclassical school

I also found Chang’s characterisation of the Neoclassical school to be inaccurate, though that school seems harder to pin down and therefore harder to characterise fairly. Chang leaves you with the general impression that the Neoclassical economists naively believes that everyone is perfectly rational and that individual utility-maximisation always ends up being better for everyone. But Neoclassicals — and even Classical economists, dating all the way back to Adam Smith — have long understood that market failures exist and are cases where governments should intervene.

The Efficient Markets Hypothesis does not assume rationality and did not cause the GFC

Chang writes:

The individualist economic model assumes the kind of rationality that no one possesses … The standard defence is that it does not matter whether a theory’s underlying assumptions are realistic or not, so long as the model predicts events accurately. This kind of defence rings hollow these days, when an economic theory assuming hyper-rationality, known as the Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH), played a key role in the making of the 2008 global financial crisis by making policy-makers believe that financial markets needed no regulation.

Okay, I do have a finance degree so feel a wee bit more qualified to comment on this — so bear with me as I pick this one apart.

There are three claims here that I think are wrong or at least highly dubious:

- First, that individualist economic models claim to predict events accurately.

- Second, that the EMH assumes hyper-rationality.

- Last, that the EMH was a key cause of the GFC.

Individualist economic models do not claim to predict events accurately

Apart from the EMH, I don’t really know which “individualist economic models” Chang might be referring to. But I’ve never heard any economist claim that their model predicts events accurately.

Economists are almost lawyer-like in the number of caveats they include alongside any model. When giving a prediction, they’ll say it’s what the model predicts and explain how the model works and what they’ve tried to control for. Any decent economist will set out the data limitations they had, uncertainty, etc.

Sure, the media may then report the predictions without including the caveats and readers may skim past them even if they do — but you can hardly blame the model (or the economist) for that.

The EMH does not assume hyper-rationality

The EMH does not claim everyone is hyper-rational. In fact, it doesn’t require market participants to be rational at all.

Let’s look at what Eugene Fama, often considered the father of the EMH, actually wrote in his seminal 1970 paper, “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work”:

A market in which prices always ‘fully reflect’ available information is called ‘efficient’.

Fama then goes on to define mathematically what he means by ‘fully reflect’. He is well aware that, in practice, the prices in a market will never ‘fully reflect’ all available information:

First, however, we should note that what we have called the efficient markets model … is the hypothesis that security prices at any point in time ‘fully reflect’ all available information. Though we shall argue that the model stands up rather well to the data, it is obviously an extreme null hypothesis. And, like any other extreme null hypothesis, we do not expect it to be literally true. [Emphasis added.]

So no one, including the father of the EMH, actually thinks any market is perfectly efficient. In fact, it’s precisely by traders exploiting inefficiencies (e.g. through arbitrage) that a market can become efficient.

Fama also gives an example of a hypothetical, “ideal” market that would be considered efficient:

For example, consider a market in which (i) there are no transaction costs in trading securities, (ii) all available information is costlessly available to all market participants, and (iii) all agree on the implications of current information for the current price and distributions of future prices of each security. In such a market, the current price of a security obviously ‘fully reflects’ all available information.

None of those criterion for a perfectly efficient market requires rationality. The third one comes closest, but even that only requires that participants agree on the implications on current information, which may not be the correct interpretation of the information. So the EMH is entirely consistent with things like bubbles and irrational exuberance.

What is critical in Fama’s concept of efficiency is that all available information is integrated into asset prices, not necessarily that the information is interpreted or used ‘rationally’ by market participants.

The EMH was not a key cause of the GFC

Causation is tricky, especially for macroeconomic events. But of all things to blame for the GFC, the EMH should be very, very far down the list, if on the list at all. (At the top of my list are the ratings agencies and the government’s failure to regulate them.)

Simply put, the EMH does not imply any policy prescriptions. It is mostly relevant for investors and speculators, not regulators. Contrary to what Chang suggests, the EMH does not tell regulators to leave markets alone. Fama merely finds that publicly available information (and especially price history) is already largely incorporated into stock prices, making it is extremely difficult to beat the market unless you have private information. It’s a descriptive theory about how markets incorporate information into prices, rather than a normative theory about how to regulate markets.

It’s possible that some people misunderstood the EMH, and such misunderstandings contributed to the lack of regulation preceding the GFC. But I don’t think it’s fair to call the EMH a “key cause” in this case.

Weak arguments

Several times in the book, I found Chang’s reasoning lacking. His ultimate conclusion may or may not be correct, but I came away feeling sceptical of how he got there. Even if space constraints prevented Chang from fully fleshing out his arguments, he should have still flagged when there was more to the story (that’s what footnotes are for!).

Specific claims I found unpersuasive included:

- China’s inability to set its own tariff policy after the Opium Wars was a key cause of its economic decline;

- Neoclassicals are wrong to draw a link between economic and political freedom; and

- raising productivity in manufacturing is easier than doing so in services or agriculture.

Many factors likely contributed to China’s decline after the Opium Wars

The first unconvincing argument was in the economic history section, where Chang discusses the Nanking Treaty. Chang argues the fact that the Treaty prevented China from using tariffs to protect its infant industries was a “huge contributing factor” to its economic decline during this period:

The most infamous unequal treaty is the Nanking Treaty, which China was forced to sign in 1842, following its defeat in the Opium War. But the unequal treaties had started with the Latin American countries, upon their independence in the 1810s and the 1820s.

… The inability to protect and promote their infant industries, whether due to direct colonial rule or to unequal treaties, was a huge contributing factor to the economic retrogression in Asia and Latin America during this period, when they saw negative per capita income growths (at the rates of -0.1 and -0.04 per cent per year, respectively).

(Chang also mentions Latin America, but I know nothing about their history, whereas I know a little about China’s.) Chang’s claim that China’s inability to protect its infant industries was a “huge contributing factor” to its decline seems overblown.

The Opium Wars occurred towards the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), which was not a great time for China. I mean, the country had just lost two pretty big wars. In addition, domestic rebellions and uprisings were common and opium addiction was rife. I couldn’t find China’s growth rates for this period, but it’s likely China’s economy was already very weak before the Treaty. It’s also worth noting that the Treaty was unequal in multiple ways. Not only did China give up tariff control, it also had to pay Britain a large indemnity in silver and cede Hong Kong.

Chang may ultimately be correct that the inability to set their own tariffs contributed the most to China’s decline. However, omitting these key facts paints an unbalanced and oversimplified causation story.

Economic freedom and political freedom do seem to be linked

Chang criticises the Neoclassical school’s focus on individual freedom, arguing that economic freedom and political freedom are different things. For example, the Scandinavian countries have low economic freedom thanks to high taxes and regulations but plenty of political freedom.

It’s undoubtedly true that economic freedom does not inevitably lead to political freedom. However:

- economic freedom in Scandinavia is not actually low; and

- economic freedom and political freedom do appear to be correlated.

While the Scandinavian countries do have high taxes, that’s only on personal income like salaries and wages. They employ a dual income tax, with high taxes on personal income but relatively low taxes on corporate and investment income.

Moreover, according to the Heritage Economic Freedom Index, the Scandinavian countries all rank well on economic freedom — consistently above average. Similarly, the World Population Review establishes indices for both Personal Freedom (freedom of speech, press, religion, etc) and Economic Freedom (taxes, costs of starting a business, international trade, etc) and the Scandinavians rank well on both of those, too.

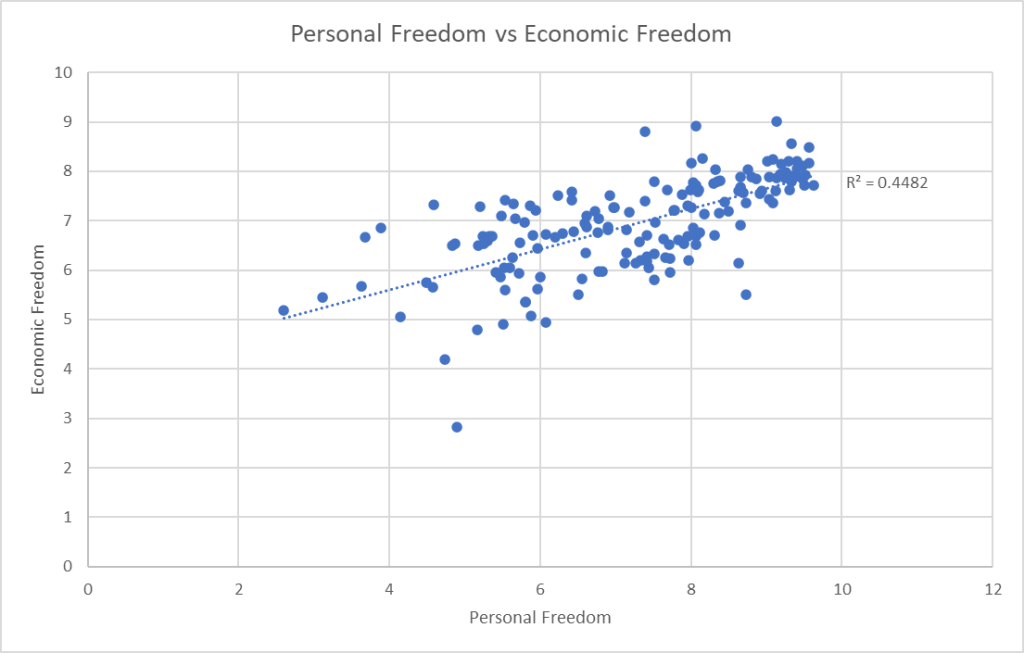

In fact, when I downloaded the World Population Review data and created a quick scatter plot of each country’s Personal Freedom and Economic Freedom. A correlation does seem to exist. Not a perfect correlation by any means, but a correlation nonetheless.

Raising productivity in manufacturing is easier than in services

An idea that Chang repeatedly promotes is the importance of a strong manufacturing sector to a country’s economic development. Chang claims that “[r]aising productivity is much easier in manufacturing than in other economic activities, such as agriculture and services”.

With agriculture, Chang explains that raising productivity is difficult because it’s very dependent on the physical environment and time-bound. It’s probably true that raising productivity in agriculture today is difficult, but agricultural productivity did increase drastically over the last century. Let’s charitably assume that Chang is saying it’s hard for a country to pull ahead by raising productivity in agriculture any further and turn to his claim about services.

Chang believes that raising productivity for services is difficult because many service activities are “inherently impervious to increases in productivity”. As such, productivity increases come at the expense of lower quality.

He uses the following examples to support his point:

- A string quartet cannot triple its productivity by playing music three times faster. (This is the classic example used to explain Baumol’s cost disease.) The phenomenon certainly exists, but not all services are like string quartets and some are highly scalable. For example, technology lets a singer make her music available to much larger audiences than in the past.

- Increases in retail service productivity come at the cost of lower service quality. Chang cites as examples fewer shop assistants, longer drives to the supermarket, and lengthier waits for deliveries. I have doubts that retail service quality has decreased (Amazon Prime’s one-day deliveries are incredibly impressive). But even when service quality declines, its accompanying cost reductions will often more-than-offset that decline. For instance, Duolingo’s nowhere as good as a private language tutor, but is vastly cheaper. Moreover, the argument that increases in productivity come at the cost of quality applies equally to the manufacturing sector. Many mass-produced goods cannot compare in quality to their artisanal, hand-crafted equivalents.

- The 2008 GFC showed that much of the recent productivity growth in finance came at the cost of inferior (overly complex and riskier) products. Chang might have half a point here but it’s an odd example as there were multiple causes of the GFC. And the GFC doesn’t show that productivity growth in finance necessarily comes with increased complexity and risk. The invention of index funds and robo-advisors seem to be possible counterexamples.

Overall, I think Chang’s claim that it’s inherently easier to raise productivity in manufacturing is poorly reasoned and possibly wrong.

Conclusion

Some of my criticisms may seem nitpicky. You could certainly argue that a handful of dubious examples in such a wide-ranging book is not too bad an error rate. But such inaccuracies undermine an author’s general credibility. If I, a non-expert, can find multiple inaccuracies so easily, it makes me wonder how many more are lurking elsewhere.

In the book’s epilogue, Chang says:

My aim in this book has been to show the reader how to think, not what to think, about the economy.

That is what I would expect from a book called Economics: The User’s Guide. Unfortunately, he didn’t really live up to that, and I wouldn’t recommend it as an introduction to economics.

That said, overall I appreciated the book. It was an ambitious undertaking, and I can imagine how hard it was to summarise so many topics in such a short space. Chang has also succeeded in making me rethink some of my beliefs. I don’t trust him enough to change my mind on any of it yet — and it may have been impossible to do so given the “introductory” nature of the book — but I’m open to hearing his arguments developed further elsewhere.

Despite my criticisms above, I still think Economics: The User’s Guide is worth a read. If you want to get it, you can do so at: Amazon | Kobo <– These are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you buy through these links. I’d be grateful if you considered supporting the site in this way! 🙂

Were there other inaccuracies or weak arguments you spotted in Chang’s book? Or do you think I’m being too harsh on him? As always, share your thoughts in the comments below!

Click here for my summary of Economics: The User’s Guide.

5 thoughts on “Criticisms of Ha-Joon Chang’s “Economics: The User’s Guide””

I think the efficient market hypothesis criticism is particularly weak and I’ve seen him make that argument several times which has put me off.

I think after the GFC, criticising the EMH became very fashionable. But sadly that’s probably down to a misunderstanding: people hear the words “efficient market hypothesis” and assume it is an assertion about markets being better operated without interference from the government (“the market is efficient”). But as you say, it’s about asset prices and why you shouldn’t just buy stocks that you hear good news about…

Chan must know that people are making that mistake but I suspect he has found it easier to lean into it rather than correct the misconception.

Yeah, I can sort of understand laypeople making that mistake but Chang should know better. It does align with his general idea that Neoclassicals believe everyone is always rational, which I guess is why he repeats it

I am really inspired together with your writing abilities as smartly as with the layout in your blog.

Is this a paid theme or did you customize it

yourself? Anyway keep up the nice quality writing, it

is rare to see a great blog like this one nowadays..

Thank you!

I use a free theme called “Sydney” by athemes, with some minor customisations 🙂

It’s the fact that Chang tells outright historical lies, such as that Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek outright supported Pinochet in his “Edible Economics” book, that really gets to me. The best thing that can be said about him is he is the not the most ideological economist I have seen. That would be Michael Hudson.