This summary of Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most by Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton and Sheila Heen explains how to better navigate difficult conversations.

Buy Difficult Conversations at: Amazon | Kobo (affiliate links)

Key Takeaways from Difficult Conversations

- Difficult conversations arise in all areas of our lives: with family, friends, and colleagues. Though the context may vary, difficult conversations tend to follow common patterns and people tend to make the same mistakes.

- There are three types of conversations that may be happening within each difficult conversation:

- the ‘What Happened’ Conversation;

- the Feelings Conversation; and

- our own Identity Conversation.

- Common mistakes include:

- Assuming you have all the facts or know the other party’s story.

- Mixing up impact and intentions.

- Focusing on who is right and who is to blame, which makes people defensive (and is usually irrelevant anyway, as being right doesn’t solve the problem).

- Going in with the purpose of changing the other person or their behaviour, since these things are not within your control.

- Ignoring feelings.

- Adopting an all-or-nothing identity.

- Doing a “hit-and-run” — i.e. raising a difficult issue in the moment when it upsets you, but there’s not enough for a proper conversation.

- What to do instead:

- Shift to a learning stance. Try to understand the other person’s story in order to develop a third story that embraces both sides’ stories.

- Disentangle impact from intentions, and reflect on your own intentions.

- Look at joint contribution instead of blame. (Blame carries judgment and implies wrongdoing, whereas contribution looks at causation without any judgment.)

- Your purpose should be to learn the other person’s story and to express your own feelings and views. Once you’ve done that, you can work together to solve the gap between your two stories.

- Share and acknowledge each other’s feelings.

- Complexify your identity so that you can better withstand any identity issues that may arise.

- Schedule a difficult conversation for when you’ll have enough time to talk properly.

- This book will not solve all your relationship problems and difficult conversations will always be challenging. However, with practice you can get better at handling difficult conversations.

- You don’t have to do anything. The book is intended to give you tools to helps navigate difficult conversations, but you don’t have to keep beating your head against the wall and you’re allowed to give up.

Detailed Summary of Difficult Conversations

Difficult conversations arise in all areas of our lives

A difficult conversation is anything you find hard to talk about. Difficult conversations are ubiquitous. In the course of the authors’ work on the Harvard Negotiation Project with thousands of people on their difficult conversations, they found that the same errors in thinking and acting in difficult conversations occur across different contexts — and even across the world.

This book is not a magic bullet. Difficult conversations will always be challenging. But you can get better at difficult conversations, and doing so will make your conversations more productive and your relationships stronger.

The Three Conversations

No matter the subject, difficult conversations fall into the same 3 types of conversations:

- the “What Happened?” Conversation;

- the Feelings Conversation; and

- the Identity Conversation.

The ‘What Happened?’ Conversation

Difficult conversations usually involve disagreement over what has happened or what should happen. The “What Happened?” conversation usually involves working out: the truth; each other’s intentions; and who’s to blame.

The Feelings Conversation

Most of us hesitate to bring up feelings because it can be uncomfortable. At work, it may also seem inappropriate. We therefore frame the problem as a substantive disagreement and try to “solve the problem”. But most difficult conversations are about feelings at their core. So unless you address them, you can’t solve the real problem.

The Identity Conversation

A conversation may feel difficult because of something beyond the apparent substance of the conversation that is at stake for you — your identity. We may not be aware of this at all because the connection is not obvious. Yet the threats to our identity can be profoundly disturbing and knock us off balance. Conversations with someone abusive will often involve identity issues as they undermine your sense of competence, confidence and self-worth.

Common mistakes and what to do instead

DON’T: Assume you have all the facts

Each of us has a different story about the world and we have different “implicit rules”

Each of us has a different story about the world because we all have different information and we interpret information differently. Neither story is necessarily wrong, they’re just different. Disagreements arise when our stories conflict

For example, the big 3 blind spots when communicating tend to be: tone of voice, facial expression, and body language. The listener is very aware of these but the talker is not. You may not be aware of how you’re coming off, and the same is true for other people.

Our views are influenced by our past experiences, and we each develop different ‘implicit rules’ based on those experiences. Often these rules take the form of what people “should” or “shouldn’t” do. For example, one person’s “It is unprofessional to be late” may conflict with another person’s “It is unprofessional to obsess about small things like being 10 minutes late”.

Trading conclusions does not promote learning

If you start a conversation assuming you’re right, you’ll spend your time delivering messages and working out how to prove you’re right, while the other person will focus on defending themselves. Neither of you will focus on listening.

Moreover, you’ll argue by trading the conclusions you’ve both reached, rather than explaining how you’ve reached those conclusions. Yet one person’s conclusion will rarely make sense in the other person’s story, so trading conclusions means we never learn how we see the world differently.

DO: Shift to a learning stance

Disagreement is not necessarily bad nor does it have to lead to a difficult conversation, if we shift to a learning stance and focus on understanding both side’s stories. This involves sharing information and asking question, instead of delivering messages:

Changing our stance means inviting the other person into the conversation with us, to help us figure things out.

Note that understanding the other side’s story doesn’t mean you have to agree with it.

Understand your own story

Make sure you understand your own story. We construct our stories so quickly and automatically that we aren’t even aware of the implicit rules we apply or everything that influences our views. While implicit rules may feel like objective truths, they are not.

When you explain how you reach your conclusions (instead of merely the conclusion itself), it’s less likely to trigger defensiveness and makes it easier for the other person to understand your perspective.

Learn the other person’s story

As the other person will have important information you don’t, especially about their intentions and implicit rules, you need to ask questions and listen to better understand their story.

Listening also helps the other person understand you. Often the reason someone doesn’t listen to you is because they don’t feel heard. They think you’re being stubborn, so they repeat themselves, talk louder, etc. You in turn do the same, because you’re not feeling heard, which leads to an unproductive cycle. By asking questions, you can direct the conversation into a more productive direction.

Tips on listening and learning the other person’s story

- Be authentic. You have to genuinely be curious and care about the other person’s story. Don’t pretend to listen if you can’t do so authentically. If you feel so overwhelmed by emotions that you can’t listen authentically, be honest and ask to defer the conversation until you can.

- Ask open-ended questions. Open-ended questions don’t bias the answer and give the other person space to respond with what’s important to them.

- Make your questions invitations, not demands. This means the other person can choose not to answer, which makes them feel safer and they’ll be more likely to respond honestly.

- Paraphrase. Putting your understanding of what someone is saying into your own words lets you check if your understanding is correct. Paraphrasing also shows the other person they are being heard. If someone keeps repeating themselves, take it as a sign to paraphrase more.

- Share what will persuade each of you. If you’re struggling to understand each other’s stories, tell each other what would persuade you of the other side’s story. Even if the person says nothing will persuade them, you’ve still learnt something — you’ve learnt that further attempts to persuade them will be wasted.

Find the third story that embraces both stories

Understanding doesn’t always solve the problem. The gap between your two stories will move closer together as you share information, but the stories may not fully converge. You’ll then have to find “the third story”, which embraces both people’s stories by adopting the “And Stance”.

Both people’s stories can make sense, and accepting the other person’s doesn’t mean giving up your own.

The And Stance is based on the assumption that the world is complex, that you can feel hurt, angry, and wronged, and they can feel just as hurt, angry, and wronged. They can be doing their best, and you can think that’s not good enough. ….

The And Stance gives you a place from which to assert the full strength of your views and feelings without having to diminish the views and feelings of someone else.

The third story doesn’t frame the problem as being one person’s fault, but as the difference or gap between the two sides’ stories. It’s the story that a neutral mediator might tell.

Start off with the third story, even if you don’t know what it is

The beginning of a difficult conversation is often the most stressful part. But it can also be the most important, as it sets the direction for the entire conversation.

Starting off a conversation from a more neutral third story is likely to be much more constructive. You can frame the problem as being the difference between your two stories, rather than being the other person’s character or behaviour.

Even if you don’t know what the other person’s story is, you can start from the third story by acknowledging you have incomplete information and inviting them to explain their side. For example:

- “My sense is that we are seeing this situation differently. I’d like to share how I’m seeing it and learn more about how you’re seeing it.”

- “The story in my head is that you are being inconsiderate. At some level I know that’s unfair to you, and I need to to help me understand where you are coming from.”

DON’T: Mix up impact and intentions

We tend to mix up impact and intentions in two ways:

- when others hurt us, we tend to assume bad intentions; and

- when our acts hurt others, we think clarifying our own good intentions means the other person should stop feeling upset.

We therefore tend to assume the worst of others based on how their actions impact us, but we treat ourselves more charitably.

When others hurt us

Intentions strongly influence our judgments of others. A double-parked ambulance blocks our way on a narrow street just as much as a double-parked BMW, yet we’ll react very differently.

Intentions are much more complex than we think, so our assumptions about others’ intentions tend to be incomplete or wrong. Intentions are rarely just “good” or “bad”. While bad intentions do exist, they’re rarer than we think.

If you accuse someone of bad intentions, even indirectly, they’ll react defensively. For example, “why did you ignore me?” to you may seem like a neutral question but the other person will likely find it accusatory. And if your assumption is wrong, they’ll feel falsely accused. This begins a cycle where both people feel like they are the victims in the conversation, and both react defensively.

When we hurt others

We often try to clarify our good intentions at the start of a difficult conversation as an act of defence. (The other person may contribute to this by accusing you of bad intentions.) We feel that once we’ve clarified our good intentions, the other party should stop feeling upset.

But starting a conversation with “I had good intentions” puts up a barrier to learning. While clarifying your intentions is helpful, make sure you understand the other person’s concerns first. If the other person’s real, possibly unexpressed, concern is that your actions hurt them, clarifying your intentions may not address the problem.

It’s also worth reflecting on your own intentions. As noted above, intentions are complex so you may not even be fully aware of what is motivating you. Even if you don’t “intend” to hurt someone, if you know that someone will be hurt by your actions and do it anyway, your intentions were not wholly good. [This is like the difference between intent and wilful blindness or recklessness in law.]

DO: Disentangle impact from intention

When another person has hurt you, explain the impact of their action on you. You should also explain your assumption about their intentions, but take care to label it as a hypothesis/guess that you are checking, rather than asserting to be true. (Don’t pretend you don’t have a hypothesis — that wouldn’t be authentic. )

Some defensiveness on the other person’s part will be inevitable, but the more you can mitigate this, the easier it will be for them to participate in a learning conversation. For example, saying “I was surprised you said this, because it was uncharacteristic for you” (assuming this is true) will make it easier for them to explain their actions and motivations.

DON’T: Focus on who is right and who is to blame

Usually both parties contributed to the situation in some way, but we tend to try and put all the blame on the other party.

You may be missing the point

Even if you are right, you may be missing the point of the conversation. A dispute is rarely about the facts but about how to interpret those facts and what they mean. These are issues involving judgment, not a black-or-white answer.

For example, in a disagreement about your daughter’s smoking, you are certainly right that smoking is bad for her health. But the conversation is not about that. It’s about what your daughter should do about it, what role you have to play, and a whole host of other complex issues and feelings.

Being right doesn’t solve the problem

And, on a pragmatic level, being right doesn’t solve the problem. Being right that your daughter should stop smoking won’t actually stop her from smoking. Being right doesn’t mean a problem will magically disappear. Even when others should do as you say, if they don’t, there’s probably a reason for it and continuing to insist that you’re right is unlikely to change anything.

It’s like a car that doesn’t go when you press the gas pedal. The car doesn’t care what your rules are about what cars should do. The car doesn’t care if you need to get somewhere. The car doesn’t care if you’re angry. The one thing we know that doesn’t help is simply continuing to press the gas pedal.

Blame provokes defensiveness

Blame provokes defensiveness and inhibits learning. No one likes to be blamed (especially unfairly), so focusing on blame makes people defensive, and not much learning follows. Even when we do need to assign blame (e.g. in court, to let people know what is expected of them), the threat of punishment makes it harder to learn the truth. So focusing on blame is unproductive.

DO: Look at joint contribution

Look at how each party has contributed to bringing about the current situation.

The difference between blame and contribution

The distinction between blame and contribution is not always easy to grasp. The key difference is that blame is about judging whereas contribution is about understanding.

Blame not only implies that you caused this, but also that you did something wrong and should be punished. In contrast, contribution is neutral. You can look at both parties’ contributions without assigning blame to either, so it’s a more constructive way of approaching the situation.

Most things do have multiple causes

Contribution better accords with reality, though it may not feel that way in the moment. Causation is complex and most things have multiple causes, though contributions may not be equal. Even an affair, which appears one-sided, often involves contributions from both partners.

Sometimes one party’s contribution may simply be avoiding a problem or appearing unapproachable, such that the other person didn’t think they could raise things with them. Other times, there may be third party contributors to the system. Unless all relevant contributions are identified, the underlying problems and patterns in the relationship may persist.

Acknowledge your own contribution

Acknowledging your own contribution early in the conversation can be helpful to signal that you’re not seeking to assign blame and may make the other person less defensive. It can also prevent that person using your contribution as a shield to avoid confronting their own contribution. That said, you shouldn’t focus solely on your contribution throughout the conversation.

Focusing on contribution does not mean blaming the victim

Focusing on contribution does not mean blaming the victim. Contribution doesn’t involve blame or fault at all; it just focuses on causes in a neutral way:

By identifying what you are doing to perpetuate a situation, you learn where you have leverage to affect the system.

[I really liked this quote. Rather than blaming the victim, it shows how focusing on joint contribution can actually be empowering.]

Work together to change the contribution system

Once you’ve identified the different elements of the contribution system, look at how to change it. Make the other person your partner in the conversation, rather than your adversary, and brainstorm options that might satisfy both parties’ needs. The task is to find a practical way forward — it’s not asking, “Who’s right?” but “given this difference in the two stories, what’s a good way to manage the problem?”

Explain to the other person what you would have them do differently in the future, and how this would help you react differently, too. Framing your request in terms of how the other person can help you change your contribution can be a powerful way to help them understand their own contribution.

Using objective standards or principles can also help resolve a matter without either side having to back down or lose face. [In the workplace, I’ve found an easy way to resolve disagreement is to try and agree instead on the process for resolution, which usually involves getting an independent person to arbitrate. It’s not quite as easy to do this in personal relationships (I don’t think many third parties want to be dragged into your relationship issues), but you may find other processes that work.]

DON’T: Go in with the purpose of changing the other person or their behaviour

If your purpose is to change the other person’s behaviour or to tell them off, the conversation is not likely to go well. You might hope for change, but ultimately you can’t control other people’s behaviour. People rarely change in response to facts and persuasive arguments but, paradoxically, when you’re not actively trying to change someone, the chance of change increases. [See also David McRaney on How Minds Change.]

[I]f you define success by what you can get others to do, you cede to them control of the outcome.

You may not want to hurt someone, or you may want them to keep liking you. But that should not be the purpose of your conversation because you cannot control their reaction, and trying to smooth things over or stifle their reaction often makes things worse. For example, even if you honestly believe that things will get better and you want to share that with them, you should still allow space for them to have their own thoughts and feelings about the situation.

DO: Have a good purpose for the conversation

Purposes that are likely to be more productive (and achievable) are:

- Learning the other person’s story.

- Expressing your own views and feelings.

- Problem-solving together.

You might hope the other person will understand and perhaps be moved by your views, but you can’t count on it.

DON’T: Ignore feelings

If you try to bottle up your feelings, they’ll end up escaping somehow. Studies show that, although most people suck at detecting factual lies, they can tell if someone is withholding an emotion. Unexpressed feelings can colour a conversation, affecting your tone, body language and facial expression. You may pause for longer than usual or come off as detached or disengaged. Feelings can also burst into a conversation. You may get angry, cry or explode despite your best efforts to control yourself.

Have your feelings or they will have you

Unexpressed feelings also make it hard to listen to another person. It’s hard to hear someone else when we feel unheard, even if the reason we feel unheard is because we chose not to share our feelings.

One way unexpressed feelings may manifest is by triggering our impulse to blame. We focus on blame as a proxy for our feelings — what you really want isn’t an admission that the other person is wrong, but an understanding and acknowledgement that they hurt you. Speaking more directly about your feelings actually reduces the impulse to blame. So when you feel the urge to blame someone, stop and consider what feelings might be hiding underneath.

DO: Share and acknowledge feelings

Before you identify your feelings, you have to identify and negotiate them.

Identify your feelings

We often don’t know how we feel because feelings are complex and nuanced. We also tend to unconsciously disguise our feelings.

Tips for identifying feelings

- Find your hard-to-express feelings. Hidden feelings may block other emotions. Which feelings were easy to discuss when you were growing up and which ones your family pretended didn’t exist? It’s not just “negative” feelings that are hard to express — affection, pride or gratitude can also be difficult for some people. And the feelings we find easy to express in some relationships (e.g. with your best friend) may be difficult in others (e.g. with your boss).

- Disentangle your feelings. There may be a bundle of feelings behind a single, strong feeling that masks the others. Behind your anger at someone, you may also be feeling a whole host of other feelings such as hopeless, confused, shame, love and caring.

- Accept your feelings. Feelings just are. Good people can have bad feelings and you won’t always like what you feel. Your feelings may not always make sense or be fair. But they are still there.

- Recognise your feelings are as important as anyone else’s. Some of us have been taught to prioritise other people’s feelings and happiness, which makes it hard to recognise our own feelings. But when we ignore our own feelings, we teach others to ignore our feelings, too. So even when you don’t raise an issue to avoid jeopardising the relationship, failing to raise it may make your resentment grow, slowly eroding the relationship anyway.

Negotiate your feelings

We can negotiate with our feelings because our feelings are based on our perceptions. Once you’ve learned more about the other person’s intent and found “the third story”, your feelings may shift. Even if your anger or hurt doesn’t disappear, they may become more manageable.

Negotiate your feelings before sharing them.

Share your feelings (not your attributions or judgments)

Don’t confuse “being emotional” with “expressing emotions clearly”. You can express emotions well without being emotional, and you can be emotional without expressing much at all.

Attributions, judgments and accusations are not feelings and are likely to trigger defensiveness. Sometimes we think we are sharing feelings when we are actually expressing a judgment that is motivated by feelings — e.g. “I feel you can be self-absorbed and thoughtless” is motivated by anger, frustration or hurt. In particular, be careful with words that carry judgments, such as “bad”, “inappropriate”, “should”, or “professional”.

Tips for sharing feelings and views

- Share even if you think your feelings are illogical. If needed, you can say you’re uncomfortable with the feeling or that you’re not sure that it’s fair. Remember that the goal is to gain a deeper understanding of each other. Prematurely evaluating whether a feeling is legitimate will undermine that.

- Express the full spectrum of feelings. When we oversimplify, we don’t express ourselves fully. A single strong feeling may mask a bundle of other thoughts and feelings. Expressing the broader spectrum adds depth to the discussion and gives the other person more to reflect on.

- Don’t be indirect. For example, tell your husband you want to spend more time together instead of telling him he plays too much golf. We often try to get our message across indirectly, through jokes, questions and body language (e.g. “Do you really need to play so much golf?” or “How do you think you’ve done?” in a performance review). But this usually backfires and increases everyone’s anxiety. Raising issues indirectly ends up triggering all the negative consequences of raising something without the benefits of clearly expressing ourselves and being understood.

- Don’t use “always” or “never”. These words are rarely accurate and will just invite a debate over frequency. They can also make it harder for someone to change their behaviour, by suggesting change may be impossible.

- Don’t ask if the other person “agrees” with your story or if it “makes sense”. This makes them reluctant to share any doubts. Instead, ask them to paraphrase your concerns back to you. If they remain confused or unpersuaded by your story, ask how they see it differently.

Expressing your views and feelings can be difficult

Some people believe that their views and feelings don’t deserve to be heard and end up unconsciously sabotaging themselves. If that’s you, remember that your views and feelings are as legitimate and important as anyone else’s. You may also benefit from an internal Identity Conversation to work out why you don’t feel entitled. Whose voice from your past do you hear telling you you’re not entitled?

That said, being entitled to express yourself doesn’t mean you’re obligated to, so don’t beat yourself up if you’re having trouble doing so. Expressing yourself authentically can be extremely difficult, and finding the courage to do so may be a lifelong process.

Listen to the other side’s feelings

Both sides can have strong feelings at the same time. Don’t monopolise the feelings conversation and make sure both parties share their feelings.

You may also need to look past what is said to what is not said — a large part of what makes difficult conversations difficult is the fact that people usually have thoughts and feelings they don’t voice.

Acknowledge each other’s feelings and views

Acknowledging doesn’t mean agreeing. It means letting the other person know that what they’ve said has made an impression on you, that their feelings matter to you, and that you’re trying to understand them. It goes both ways — make sure the other person also appreciates how important this topic is to you and that they truly understand your feelings.

Acknowledging feelings can be particularly important in “intractable” conflicts. Sometimes a person doesn’t actually want any change or may understand that change is impossible, but just want to be heard.

Don’t jump to fixing the problem

Acknowledge each other’s feelings and views before fixing the problem. It can be tempting to short-circuit this acknowledgement and jump straight to fixing the problem — e.g. “Okay, if you’re feeling lonely, I can try and spend more time with you.”

But acknowledgement is an important step. We need to make sure we’ve fully understood the other side’s real concern before trying to fix the problem. Moreover, until someone feels like their feelings have been acknowledged, they’ll have trouble moving forward in the conversation.

DON’T: Adopt an all-or-nothing identity

All-or-nothing thinking makes your identity vulnerable. You’re either competent or not, a good person or not.

When we engage in all-or-nothing thinking, we become hypersensitive to feedback that may threaten our identities and respond by either:

- Denial. We might cling to a purely positive identity by denying any negative feedback outright, even if they’re just small mistakes. But over time, if we keep getting more negative feedback that we have to deny, it becomes easier to lose balance.

- Exaggeration. Exaggeration is the opposite of denial. We exaggerate a piece of feedback, by acting as if that feedback is the only thing that matters. If we turn in 100 memos on time, but are late with the 101st, we start thinking we can never do anything right.

Remember that the other person may also be grappling with their own identity issues. If so, one way you can help them is by leading them away from all-or-nothing thinking. For example, you can point out that all people need help sometimes, to reduce any threat to their sense of competence.

DO: Complexify your identity

Unfortunately, there’s no quick fix when a conversation implicates our identity. But there are ways you can improve your ability to recognise and cope with them by grounding your identity before a difficult conversation.

This involves two steps:

- First, identify your identity issues. Three common identity issues involve: your competence, whether you’re a “good person” and whether you’re worthy of love. Try to spot common patterns to the things that knock you off balance during difficult conversations and ask yourself why. How would it feel if those things were true?

- Next, complexify your identity to make it more robust. Move beyond all-or-nothing thinking by adopting “the And Stance”. No one is always anything, so try to get a more objective picture of yourself. In particular, learn to accept that: you will sometimes make mistakes; your intentions are complex; and you have likely contributed to the problem.

In addition to grounding your identity, you can prepare for the other person’s response. Try to imagine beforehand how the conversation might go and consider if it might raise identity issues for you.

When to raise a difficult conversation

We often find it hard to decide whether to have a difficult conversation at all. We think that raising the issue might make it worse, and perhaps the issue will go away by itself or we’ll get used to it. Yet we also know that avoiding the problem will likely leave us unhappy and cause our feelings to fester.

Unfortunately, there’s no way to know in advance how a conversation will go, but there are some things to consider in making your decision:

- Sometimes it’s easier to clear the air earlier. While it can be tempting to avoid psychological pain in the short-term by giving in, this can be a poor long-term strategy. Giving in rewards the difficult behaviour and doesn’t address the underlying issue. Sometimes raising an issue or correcting a misunderstanding earlier can clear the air with much less time and energy.

- Don’t do a ‘hit-and-run’. A “hit-and-run” is where you raise an issue on the fly because it’s causing you frustration right now and you want to get it off your chest. If you’re going to talk, make sure you plan a time to talk and allow enough time for it. You can’t have a real conversation in 30 seconds, and anything less than a real conversation won’t help.

- Don’t raise the issue when the real conflict is with yourself. Work through the Three Conversations when deciding whether to raise something. If what’s making a conversation difficult is more to do with you than the other person, it may not make sense to raise the issue you’ve had a longer conversation with yourself first. Similarly, there may be a better way of addressing the issue, such as by changing your own contribution to the problem.

Most people give up too early

Change isn’t easy and may feel awkward at first. Even after reading this book you will find yourself slipping back into some bad habits. The advice may seem simple — even simplistic at times — but executing it well will still be challenging. The same is true for the other person. Even if they understand the impact their behaviour has on you and agrees to change it, they aren’t perfect and may find it challenging to do so. Most difficult conversations are not a single conversation but a series of exchanges over time.

However, when people think a situation is beyond fixing, they are usually wrong. You won’t know if your story is the more reasonable one until you’ve explored the other side’s story, and most of us give up and let ourselves off the hook too early. Moreover, even where a substantive disagreement remains, you may still be able to gain a better understanding of each other’s perspective. This may help you separate out the substantive disagreements from the importance of your relationships.

But you are allowed to give up and let go

Sometimes people do have bad intentions and some situations are truly hopeless, no matter how skilled you become. And you or the other person may simply not want to invest in the relationship or work things out.

Letting go usually takes time and is probably different for each person. The authors suggest 4 liberating assumptions that can help:

- It’s not my responsibility to make things better; it’s my responsibility to do my best.

- The other person has limitations too.

- This conflict is not who I am.

- Letting go doesn’t mean I no longer care.

People often approach the authors describing how someone in their life was just impossible to deal with. At first, the authors tried to give advice, but each suggestion would be quickly dismissed. After a few years, the authors realised the people didn’t want advice — they wanted permission to give up. When the authors instead told them, “Sounds like you’ve done your best already”, they were delighted.

You don’t have to do anything. You don’t have to keep beating your head against the wall or stay in a relationship that’s undermining your self-esteem. Ultimately, this is a pragmatic book that gives you tools to better navigate difficult conversations. But you’re allowed to give up.

Other Notes

Keeping a conversation on track

During a difficult conversation, you probably will get knocked off course. The key is to get back up and steer the conversation in a productive direction.

Tips to keep a conversation on track

- Take a break. If it gets to be too much, take a break and go for a walk. Get some perspective by imagining that it’s sometime in the future — did the outcome of this conversation matter? What will you have learned from it?

- Reframe. If the other person keeps focusing on blame and judgments, try to reframe what they’ve said into the concepts above. Blame can be reframed into contribution, judgments can be reframed into feelings, truth can be reframed into different stories.

- Name the dynamic. Sometimes it helps to explicitly name a troubling dynamic in the conversation. However, naming the dynamic can also backfire by increasing tension or taking the focus off the substance of the conversation, so it’s best used as a last resort.

- Acknowledge the other person’s power. Explicitly acknowledging the other person’s power and autonomy can make them more receptive to your input. For example, when raising an issue with your boss, you could start by acknowledging that you know they have to balance a bunch of competing considerations and that you’ll abide by whatever decision they end up making.

Emails and texts

Emails are serial monologues and don’t offer opportunities to interrupt for clarification, gauge the other’s reaction or test assumptions. They also fail to convey tone, body language and facial expressions, increasing the chance of misunderstanding. Anything you write can be taken the wrong way.

Once any sort of emotion is in play, you should switch to in-person conversations or at least the phone. If you have to use email or phone, be extra careful and make sure to be explicit about your intentions and reasoning.

A note about examples

Difficult Conversations employed lots of examples effectively.

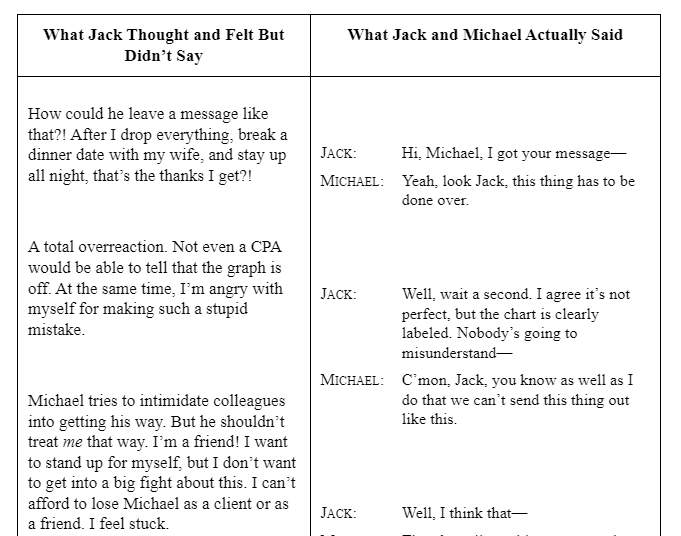

For instance, the main example involved two friends, Michael and Jack, in a work-related dispute. Michael had asked Jack at short notice to produce a brochure and Jack had done so — but with a few mistakes. The authors really drill down into their conversation, breaking down what the two men are silently thinking and feeling alongside what they are saying:

This detailed analysis of an (admittedly fictitious) example was a powerful way to show just how complex a typical “difficult conversation” is, with many things going on beneath the surface. The authors return to Michael and Jack’s example repeatedly throughout. They also use plenty of smaller examples, which are similarly effective at demonstrating how to apply their principles in real life.

I’ve omitted most examples throughout the summary, focusing instead on the theory and principles. But I’d encourage you to read the book if you want to understand how these principles look in practice. I found a few of them struck eerily close to home!

Ten questions people ask about difficult conversations

The edition I read also included the authors’ answers to ten frequently asked questions about difficult conversations at the end:

- It sounds like you’re saying everything is relative. Aren’t some things just true, and can’t someone simply be wrong?

- What if the other person really does have bad intentions – lying, bullying, or intentionally derailing the conversation to get what they want?

- What if the other person is genuinely difficult, perhaps even mentally ill?

- How does this work with someone who has all the power – like my boss?

- If I’m the boss/parent, why can’t I just tell my subordinates/ children what to do?

- Isn’t this a very American approach? How does it work in other cultures?

- What about conversations that aren’t face-to-face? What should I do differently if I’m on the phone or e-mail?

- Why do you advise people to “bring feelings into the workplace”? I’m not a therapist, and shouldn’t business decisions be made on the merits?

- Who has time for all this in the real world?

- My identity conversation keeps getting stuck in either-or: I’m perfect or I’m horrible. I can’t seem to get past that. What can I do?

I’m not going to summarise the answers here, which are rather lengthy. However, I’ve tried to incorporate some of the key points into my summary so you may be able to guess the answers based on what I have summarised.

My Thoughts

I really enjoyed Difficult Conversations. The book is intensely pragmatic and their advice made a lot of sense to me. It seems like the authors drew on their legal backgrounds in coming up with some of the concepts in the book — e.g. the distinctions between blame vs contribution, facts vs judgments, and intention vs wilful blindness. I also appreciated that the authors didn’t oversell the book, admitting upfront that difficult conversations will always remain challenging.

I’ve certainly been guilty of many of the mistakes the authors described. Parts that particularly resonated with me were:

- Being right doesn’t solve the problem. This sounds so obvious, but is all too easy to overlook.

- Blame is often a proxy for our feelings, when what we really want is an understanding and acknowledgement that the other person hurt you.

- “Hit-and-runs” are a terrible way to raise real issues.

- People who approached the authors about someone “impossible” in their lives actually wanted permission to give up rather than advice.

I’ve since tried to put the book’s advice into practice. While it hasn’t magically solved all my relationship issues, the results have been positive so far and I’m hopeful I’ll continue to get better at difficult conversations with practice.

A minor nitpick is that the book was rather repetitive. My first draft of the summary followed the book’s structure much more closely, but I subsequently streamlined it. That said, repetition can still be useful in driving home the key concepts. The principles sound very simple — obvious, even — but are much harder to apply in practice. This is a book I was fine spending hours on, because I think it really needs to be “studied” rather than simply read.

Buy Difficult Conversations at: Amazon | Kobo <– These are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase. I’d be grateful if you considered supporting the site in this way! 🙂

Have you read Difficult Conversations? What do you think of its advice? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

If you enjoyed this summary of Difficult Conversations, you may also like:

4 thoughts on “Book Summary: Difficult Conversations by Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton and Sheila Heen”

This sounds really good. I think I’ll check it out, although I’ve got a huge pile of books to read now…

Lots of the summary about types of difficult conversations resonated with me, and the excerpt from the Michael/Jack conversation seems familiar.

I had a go at making a ChatGPT prompt out of your notes. I tried it on a fake dispute and it seemed pretty good! Here it is:

You are an expert coach for having difficult conversations. You work with a user to coach the user how to approach a difficult conversation. You gather all the context you can, inquire about what the other party might be thinking, and suggest an approach. After you make suggestions, the user will ask you questions, or report back results, and you iteratively work through the issue with the user. Here are your general principles from years of work:

Understanding Difficult Conversations

🧩 Three Conversations: What Happened, Feelings, Identity.

🧠 Common Mistakes: Assuming facts, blaming, ignoring emotions.

🔀 Shift to learning; embrace both perspectives.

Strategies and Techniques

🧭 Separate Impact from Intentions: Acknowledge complexity.

⚖️ Joint Contribution, Not Blame: Focus on collaborative resolution.

💌 Purpose: Learning and expressing feelings, not controlling others.

💬 Share Feelings: Encourage open dialogue.

🚫 Avoid All-or-Nothing Thinking: Embrace your complexities.

⏱️ Plan Time for Talk: No “hit and runs.”

Communication Methods

📧 Emails: Not suitable for emotional issues.

🔄 Practice: Improvement comes with effort.

Specific Advice

📚 Adopt a learning mindset.

🤝 Separate impact from intent.

🚫 Avoid blame; look for joint contributions.

😊 Share feelings openly and authentically.

👂 Listen actively.

📖 Find the “third story.”

🗣️ State issues respectfully.

✉️ Make requests, not demands.

🧘♂️ Have realistic expectations.

💺 Take breaks if needed.

🗓️ Schedule intentional time.

👥 See nuance in yourself and others.

🌱 Be open to learning.

💔 Remember relationships can be repaired.

Conclusion

🚶 You can walk away if needed.

🛠️ Pragmatic advice, not a silver bullet.

Are you ready to start?

Thanks! I tried it out on a dispute too and it was pretty useful. Not so much the initial response but when I asked further questions.

One thing it was really good at was helping me disentangle feelings by working out what feelings I *might* have in a situation, but be unable to articulate. I gave it a fact pattern along with a very general feeling like “frustration” and ChatGPT was able to suggest a bunch of other feelings (e.g. anxiety, disappointment, exhaustion), some of which rang true.

Cool. I think initial mega prompts are ok, but they’re not as powerful as some people imagine. You do tend to get a lot out of ChatGPT by engaging in long conversations and redirecting it, and that probably can’t be replicated with a single long prompt. But I think the initial long prompt can orient it to the sort of thing you are after maybe a bit quicker than few-shot prompts.