Hannah Ritchie’s book Not the End of the World covers a range of solutions for each of the 7 major environmental problems she discusses. However, since our environmental problems tend to be closely related, there’s a good deal of overlap between the many solutions.

Instead of organising by the environmental problem each solution aims to fix, I’ve sorted them here into three categories:

- the good — the environmental solutions that actually work;

- the not-so-effective — things to stress less about; and

- the downright harmful — things that feel ‘green’ but are actually counterproductive.

While I don’t cover every single solution mentioned in the book (there are a lot), I cover the most effective and interesting ones. I also give some of my own brief thoughts on the solutions.

You can also check out my summary of Not the End of the World and a list of the environmental myths that the book debunks.

The good

I’ve split this section up into:

- individual-level solutions; and

- systemic-level solutions.

This split isn’t perfect, because systemic solutions are ultimately carried out by individuals. But it can still be helpful to see what actions you can do as an individual vs those that would require co-operating with others over a longer period.

Individual solutions

The main things you can do as an individual are:

- Eat less meat, especially beef and lamb;

- Eat fish that is certified as sustainable;

- Take cleaner transport options;

- Vote with your wallet;

- Use your career to make a difference; and

- Vote for leaders who support sustainability.

Eat less meat, especially beef and lamb

Ritchie acknowledges that what people eat is deeply personal, and she’s not trying to tell people what to eat. But she wants people to have accurate information so that they understand how to eat more sustainably if they so choose.

Meat is a terribly inefficient food

Food lies close to the heart of almost all of our environmental problems. The amount of land we take up (around 1% of habitable land) pales in comparison to the amount we use for agriculture (around 50%). In a way, this is good news, because one change—like eating less meat—can have major benefits that cut across multiple domains.

The reason why eating less meat can be so impactful is that producing meat, especially beef and lamb, is a terribly inefficient way of feeding ourselves. Bigger animals are less calorie-efficient because we need to feed them more food to keep them alive. For beef and lamb, only 3 to 4% of the calories we feed them translates into the final product we eat. For pork, it’s almost 10% and chicken is at 13%. The same applies to protein. More than 90% of the protein that cows, sheep and pigs eat from animal feed is lost. Chicken is not much better, losing around 80%.

Because of this inefficiency, meat production is the largest driver of deforestation, which is bad for both biodiversity and carbon emissions. Around 75% of global agricultural land is used for livestock—grazing them and growing crops to feed them. There’s a rich-poor gap here—while poorer countries use over 90% of their cereal crops for human food, many crops in rich countries go to feed livestock.

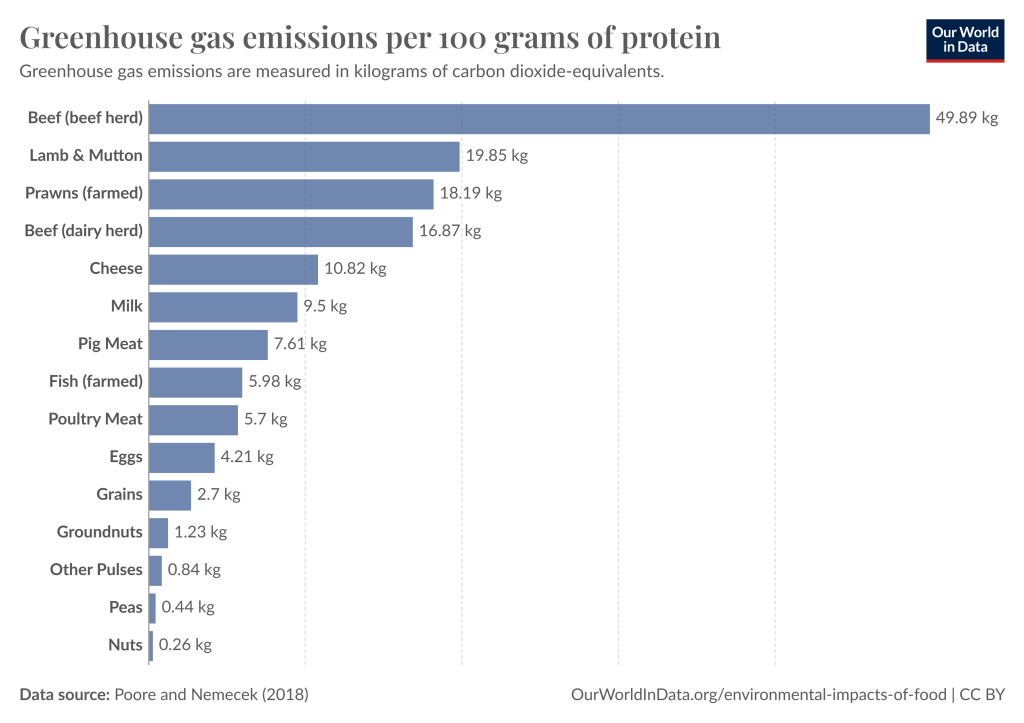

The graph below shows that producing beef emits more greenhouse gas emissions per gram of protein than other foods—by a lot. Literally over 100 times more, compared to some plant-based options.

Globally, we produce enough food so that everyone could have more than twice their calorie needs. But not if everyone ate meat. (Of course, food is not just about calories. However, Ritchie’s PhD research showed that the world produces enough of all the nutrients we need to feed everyone, too.)

So the single best thing most of us could do for the environment is to eat less meat and dairy. Cutting out beef and lamb (but keeping dairy) would nearly halve the amount of farmland we need. Switching from a beef burger to Beyond Meat or Impossible Burger would result in a 96% drop in emissions.

You don’t have to go fully vegetarian or vegan

Meat and dairy do have some benefits—one is that they are complete protein sources (i.e. they contain all essential amino acids). While it’s possible to have a nutritious diet without meat and dairy, it’s not feasible for everyone because it requires planning, knowledge and possibly some supplements.

We’d get much greater environmental gains if a large number of people altered their diets slightly (e.g. by going meat-free 2 days per week) than if a small number made drastic changes (e.g. increasing veganism by a few percent).

Even swapping out beef eater for chicken or fish would make an enormous difference—bigger than swapping out chicken for plant-based protein. (From an environmental standpoint rather than animal welfare, of course.)

Eat fish that is certified as sustainable

Fish are a fairly low-carbon option. There are some exceptions, like flounder and lobster, but most of the popular fish we eat—tuna, salmon, cod, trout and herring—are environmentally-friendly provided they are sustainably caught or farmed.

Look for fish with certification labels from the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) or Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC). While they aren’t perfect, these councils monitor and check the sustainability of fish against a list of standards.

There may also be guides in your country that rate specific fish populations based on independent assessments. For the UK, Ritchie recommends this Good Fish Guide. For the US, Ritchie recommends Seafood Watch.

Take cleaner transport options

Driving less where possible is one of the best ways to reduce air pollution and climate change. Taking fewer flights also significantly reduces your carbon footprint.

Switching to an electric vehicle (EV) also helps. It takes more energy to manufacture a new EV than to manufacture a new petrol car or to keep an existing car, but driving an EV emits much less carbon. The breakeven point depends on how clean your electricity is. In the UK, the breakeven point is:

- less than 2 years compared to a new petrol car; or

- 4 years compared to an existing petrol car.

But don’t use biofuels. They often emit more CO2 than petrol or diesel, especially if you take into account land use.

Vote with your wallet

Every time we buy something, we send a market signal.

New technologies cost more when they first start out, but come down in price once they’ve reached sufficient scale. For example, electric car batteries in the 1990s cost as much as $1 million. Now they cost between $5,000 to $12,000. If we can get meat substitutes or lab-grown meat to be cheaper than traditional meat, it could be a gamechanger.

So consumers who are able to buy environmentally-friendly products while they’re still new and expensive can show businesses and their investors that there is a demand for these products.

Use your career to make a difference

Ritchie gives a general plug for donating to effective causes and using your career to make a difference. Apart from 80,000 Hours (for careers), she doesn’t name any organisations, so I’ve just focused here on specific environmental solutions.

The Ocean Cleanup

Boyan Slat founded a non-profit called The Ocean Cleanup when he was just 18. The Ocean Cleanup works on developing technology to reduce the amount of debris in the world’s oceans. One of their inventions is the Interceptor Original, a solar-powered device that intercepts debris coming out of rivers before it can reach the ocean.

It’s too early to say how scalable these solutions are, but people are working on this.

Vote for leaders who support sustainability

President Nixon was one of the “greenest” leaders in history, because he set up the Environmental Protection Agency and passed both the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act.

But Nixon himself didn’t really care about the environment—he only did those things because the public demanded it.

This leads us to the next section—systemic solutions. A single positive policy change can be more effective than the individual efforts of millions. Ritchie also explains in her book some of the policy changes that might fit that bill.

Systemic solutions

The idea that we could solve our environmental problems if everyone just did their part and wasted a little less is wishful thinking. During the Covid-19 pandemic, most of the world stayed home. There were hardly any cars or planes operating. Yet global CO2 emissions fell by merely 5%.

Real and lasting progress requires large-scale systemic and technological change. Effective systemic solutions include:

- Shifting to renewable or nuclear energy;

- Transfers to developing countries;

- Paying to stop deforestation; and

- Regulations.

Shifting to renewable or nuclear energy

Shifting to renewable or nuclear energy kills two birds with one stone, by addressing both air pollution and climate change.

A common misconception is that nuclear power is unsafe. Nuclear and renewables are actually the safest sources of energy. Pollution from coal and oil kill hundreds, if not thousands of times more people per unit of electricity produced.

One way to implement this shift may involve carbon taxes. The current prices we pay for things don’t reflect their full costs (including environmental costs). A carbon tax could make the environmentally destructive decisions costlier for the consumer, so they’d have a greater incentive to choose an environmentally friendlier option.

Ritchie is indifferent on whether renewables vs nuclear is better. Either would be such a massive win compared to fossil fuels. We often spend our time fighting with those whose views and values are closest to us, when we’re really on the same team. When we fight amongst ourselves, we fail to put up resistance to the real opponents—the fossil fuel companies. Debate can be helpful, but it should be constructive and generous.

Helping developing countries

Ritchie advocates helping developing countries on two broad grounds.

The first ground is about fairness. The poorest countries in the world have contributed almost nothing to climate change, but will be the ones that suffer its worst impacts. Ritchie therefore argues that rich countries should contribute to financing adaptation measures (e.g. improving health care facilities, increasing air conditioning, etc).

The second ground is more about effectiveness. If we want to solve certain environmental problems, the most effective approach may be to help poorer countries transition to cleaner practices or technologies, which may be more expensive in the short-term.

Some examples:

- Clean energy. We already have technologies for cleaner energy, but transitioning can be expensive. Some in developing countries still rely on wood as their main source of energy.

- Farming practices. Technologies like cross-breeding and genetic modification could increase crop yields in sub-Saharan Africa. There are also inventions like the Happy Seeder, which helps farmers turn over their fields for the next crop in a more environmentally-friendly way than simply burning off the previous crop’s residue.

- Food supply chains. In developing countries, a lot of food waste occurs in supply chains and storage. One study in South Asia found that switching fabric sacks for plastic crates reduced food losses from 20% to 3%. Refrigeration and plastic wrap can also increase the shelf life of food.

- Waste management. Waste management is a solved problem in rich countries. But when countries transition from low- to middle-income and starts consuming more, their waste infrastructure often can’t grow fast enough to cope. So rich countries could support other countries in building systems to collect rubbish from households to landfills, and sealing their landfills so that rubbish can’t escape.

Pay countries to stop deforestation

Deforestation occurs because it’s profitable—people want timber to build stuff and land to be converted to agriculture. So if a country leaves its forests standing, they’re leaving money on the table.

We should therefore pay countries to stop deforestation. Compensation schemes like REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries), have already had some success. But the funding so far has not been close to what’s needed—only a handful of countries have chipped in, with Norway leading the way.

Stopping deforestation is a relatively cheap way of reducing carbon emissions—much easier than stopping people’s beef consumption. Some people already pay to offset their emissions by planting trees, but paying to stop deforestation in the first place is more cost-effective, and has greater biodiversity benefits.

Regulations

Environmental regulations work. They’ve played a key role in solving problems of air pollution, acid rain, the hole in the ozone layer, and overfishing.

Other regulations Ritchie advocates include:

- Industrial producers and plastics. Industrial producers should streamline the plastics they use, and the plastics should be recyclable.

- Limiting by-catch. Around 10% of the fish caught globally are discarded, because they weren’t what the fisherman wanted to catch. Bottom-trawlers have a worse discard rate, of around 20%. Some countries have laws requiring fishermen to keep all of their catch, which counts towards their quota. This incentivises people to be much more careful about by-catch and use more targeted equipment.

- Penalties for losing or dumping fishing gear. Check how much equipment fishing vessels have when they set out for sea and cross-check it when they return. We could impose fines or temporary bans if fishing gear, ropes or nets have been dumped at sea.

The not-so-effective

The things most people say they do to reduce their carbon footprint often has a tiny impact—e.g. recycling, using more efficient light bulbs, or hanging out their washing to dry.

While small positive impacts may be better than nothing, they come with a risk of moral licensing. If we feel we’ve done one ‘good’ thing already, we tend to feel justified in being ‘bad’ (or complacent) elsewhere. So we should make sure our ‘good’ actions are actually effective.

I don’t mean to be too down on recycling. I still tell my friends to do it. I still do it. … But if it’s the only thing you do or one of the biggest things you do for the environment, then you need to up your game.

Recycling or using less plastics

Many people are concerned about the plastics we use—in food and drink packaging, plastic bags and straws.

But there’s a reason plastic is so ubiquitous—it’s really useful. Plastic packaging keeps food fresh, which reduces food waste. Plastic is also cheap and easy to make—single-use plastic bags actually have a lower environmental footprint than paper and cotton bags (you’d need to use a cotton bag tens to hundreds of times before you hit the breakeven point). And plastic is reasonably durable—plastic straws don’t get soggy like paper ones.

Paper is made of a compound called cellulose, which dissolves in water. Why anyone would think it’s a good idea to make drinking straws out of paper is beyond me.

The problem with plastic is not how they’re made, but how they’re disposed of. Recycling plastic is good, but not that good because most plastics can only be recycled once or twice before being sent to landfill, because it degrades each time.

Even going straight to landfill isn’t that bad in countries with good waste management systems (which is most rich countries). In some poorer countries, there may not be a regular collection service to take rubbish to the landfill, or landfills may not be properly sealed, so rubbish can escape and end up polluting rivers and oceans. But when landfills are properly sealed, plastic can’t escape. (And, contrary to popular belief, we are not running out of space for landfills.)

Plastic pollution is the most tractable problem discussed in Ritchie’s book—we just need good waste management systems, which most rich countries already have.

Eating locally produced food

Eating local usually doesn’t make a big difference to carbon emissions, and might even be counterproductive in some cases.

It doesn’t make a big difference because long-distance shipping is actually pretty efficient. Transport makes up around 5% of the total emissions involved in producing food, and almost all of that is from the transport on local roads, not the international portion. If foods are flown rather than shipped, this isn’t true. But shipping is much cheaper, so companies will only choose air transport if the food has a very short shelf life (e.g. asparagus, green beans and berries).

Eating local could even be counterproductive in some cases if we use more energy to grow foods better suited for other climates. For example, eating tomatoes produced in greenhouses in Sweden can use up to 10x the energy as importing tomatoes.

While there may be valid reasons to eat locally produced food, wanting a low-carbon footprint is not one of them. What we eat matters much more than how it gets to us.

Counterproductive stuff

Environmentally-friendly solutions often feel unintuitive. Many of us succumb to the natural fallacy—the idea that ‘natural’ things are good and ‘unnatural’ things are bad. This is why environmentalists often dislike lab-grown meat, dense cities, nuclear energy, genetic modification, synthetic fertilisers and pesticides, and even microwaves.

Although the natural fallacy is understandable, it’s wrong and can even be harmful, as in the examples below.

Eating organic

Overall, organic farming is much worse for the environment than conventional farming. While its record on greenhouse gas emissions is mixed, organic farming fares worse on both land use and water pollution:

- Land use. Synthetic fertilisers and pesticides vastly increase crop yields. This means we need less land to get the same amount of food, and can return some of it to forest. Humans currently use around 50 million km² of land for farming. If we returned to early, organic methods of farming, we’d need somewhere between 80 to 800 million km², depending on what food is produced.

- Water pollution. Organic farming uses manure as fertiliser. Much of this is washed away into rivers and lakes where it causes algal bloom.

[W]e can’t go backwards. It’s tempting to think we should return to a way of producing food that seems more rooted, more grounded, in how things used to be. These methods can work at a small scale. But they don’t feed billions.

Some people may choose organic for health-related reasons and concerns about pesticides. However, there’s little evidence to show that organic food is generally healthier. If you live in a place with good food governance bodies, non-organic food will be perfectly safe.

Eating grass-fed beef

Like organic farming, grass-fed beef requires more land than grain-fed. Cows raised on grass alone need 2-3 times as much land.

But there is, unfortunately, a trade-off between animal welfare and environmental impact here.

Boycotting palm oil

Palm oil is an incredibly productive plant—that’s why it’s so popular. One hectare of palm yields 2.8 tonnes of oil, compared to 0.3 tonnes at most for one hectare of olives or coconuts. So replacing palm oil with olive or coconut oil would require a lot more farmland. (And, since coconuts are a tropical crop, it could increase deforestation in tropical areas where biodiversity is likely richer.)

Instead of boycotting palm oil altogether, you should buy palm oil that’s been certified sustainable. The most well-known certification is the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)—their rules are not perfect, but they have had success in reducing deforestation in Indonesia.

Vertical farms

While vertical farms use considerably less land, water and fertiliser than ordinary farms, they need a lot of energy and our electricity isn’t yet carbon-free. Even when it’s feasible, it’s only barely so, and only for a few crops (none of our staples).

Rural living

Rural living may feel eco-friendly, but cities are actually much better on that front. A city’s density allows for infrastructure that prioritises walking, cycling or public transport, reducing the emissions per person. As people have migrated from rural areas to cities, we’ve been able to intensify farming, freeing up land for forests to regrow.

There’s also been a recent surge in popularity for wood fires and stoves, but burning wood produces a lot of air pollution. It’s even worse for the environment than coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel. Per kilogram, coal releases about twice as much energy as wood.

My thoughts

I often feel like I’m being bombarded with so many things I “should” or “shouldn’t” do for the environment, and it’s hard to sort out the solid advice from the ineffective virtue-signalling. When requests are too demanding, my motivation tends to flag and I start to question if it’s worth trying at all.

So I appreciated how Not the End of the World lays out so many environmental solutions and discusses them in a factual, evidence-based way, without much moralising. It’s good to know that we don’t have worry about every paper towel or Ziploc bag we use.

I found the graph showing the carbon emissions for different types of food eye-opening. I’d heard before that beef was better for the environment than chicken, but I’d also heard that chicken was better than beef in terms of animal welfare because you don’t have to kill as many animals to get the same amount of meat. And I figured the two arguments just kind of cancelled out, so I didn’t need to change my behaviour. (Of course, I knew that not eating meat would be the best on both fronts, but that would’ve fallen on the “too demanding” bucket.)

But seeing just how big the discrepancy between beef and chicken was has made me rethink my stance. I was already trying to eat less beef (for selfish reasons) and this gave me further motivation to do so.

Do you have a friend who cares about the environment but is going about it ineffectively?

Consider sharing this post with them! (In a gentle, helpful way)

If you liked this post, you should also check out:

2 thoughts on “Solutions in “Not the End of the World””

This has a really interesting discussion of chicken vs beef.

https://www.astralcodexten.com/p/moral-costs-of-chicken-vs-beef

But seems like there’s a difference in environmental impact in the sources. Your chart shows 10x for beef whereas Scott Alexander is citing 5x

I think the difference between the OWID of almost 10x figure and Scott Alexander’s 5x figure is because the OWID chart is emissions for a given amount of protein while Alexander’s figure is emissions for a given number of calories. Chicken has a higher protein to calorie ratio compared to beef (which is one of my selfish reasons for trying to eat less beef).

While I do give weight to the animal suffering issue, that can be mitigated by consuming chickens raised in more humane conditions (that would increase the climate impact, but I doubt it would be by a 10x factor).

I’m pretty sceptical of the figure Alexander uses of about $6 to save one chicken life because it’s derived by looking at how cost-effective it was to influence people into eating less chicken/pork by showing them disturbing videos (in fact, I’m surprised that showing disturbing videos is as cost-effective as that!). But anyway, I care more about mitigating suffering than about saving a chicken’s life. Since the vast majority of chicken lives would not have existed if we did not eat chicken, I feel like as long as their life is not overall negative, then it’s not really that bad. Of course, most chickens are currently raised in conditions such that their lives are overall negative and, unfortunately, it’s not always easy to find ethically-raised ones.