The Pyramid Principle: Logic in Writing and Thinking by Barbara Minto explains how to make your writing clearer by imposing a logical structure on it. The book was first published in 1987. My summary is for the 2009 revised edition.

While the book focuses on writing in a business context (Minto was a management consultant), most of the principles—including the key pyramid structure—can apply to many other forms of non-fiction writing.

Estimated time: 21 mins

Buy The Pyramid Principle at: Amazon (affiliate link)

Key Takeaways from The Pyramid Principle

- To write clearly, separate out your thinking and writing:

- Our thinking is often bottom-up. We form sentences that contain individual ideas, then we group logically-related sentences into a paragraph, and then group logically-related paragraphs into sections.

- But when we write, we can only present one idea at a time. To help your reader understand your ideas, you need a logical structure that is top-down.

- The pyramid structure helps us visualise how different ideas relate to each other:

- Ideas at the top of the pyramid summarise the group of ideas below it.

- Ideas at the lower levels explain or defend the points above.

- Ideas at the same level sit alongside each other at the same level of abstraction.

- A key advantage of the pyramid structure is that it aids the reader’s comprehension and helps them keep ideas together in their working memory. A clear structure should also allow for easy skimming.

- Form logical groups for your ideas, using one of four analytical processes:

- Deductive reasoning. Reaching a new conclusion from two related premises.

- Chronological. This is good for cause-and-effect relationships where you are prescribing certain steps or recommendations.

- Structural. When you divide something up into parts, make sure those parts are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive.

- Comparative. If you group ideas together because they share some characteristic, explain why that shared characteristic matters.

- Presenting your pyramid:

- At the top, your introduction should (uncontroversially) set out the Situation, Complication and Question for your document before giving the Answer.

- In the middle, you’ll present your logical groupings, pausing and recapping in between each major group.

- Conclusions are difficult to do well and not usually necessary. But it can be a bit awkward to just stop writing, so you can finish with something like a summary or next steps.

Detailed Summary of The Pyramid Principle

Separate out your thinking and writing

When we write, we have to work through a bunch of points in our heads before putting them down into words. Sometimes we may only have a vague idea of the logical structure when we start. Other times we might think we know what we’ll write, having thought about an issue for a long time, only to discover when we try to write things down step-by-step that we’ve missed an important point.

To write clearer documents, we should separate out the thinking and writing processes so that we complete our thinking before we write. If we do this well, our documents should be clearer and shorter, and save us a lot of time writing and re-writing.

Thinking is often bottom-up

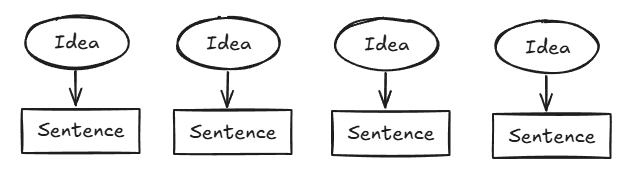

Our thinking often proceeds in a bottom-up way. First, we form sentences that each contain an individual idea.

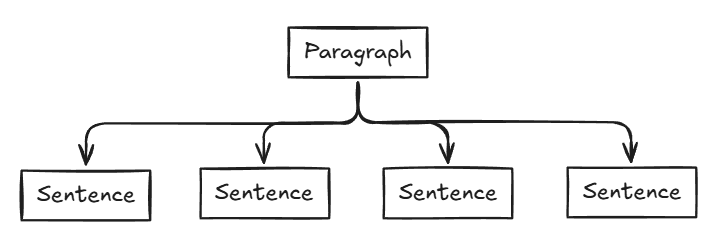

Then we group several logically-related sentences together into a paragraph. Each paragraph itself contains a single idea, which is effectively a summary of the sentences within it.

Once we’ve grouped 4 sentences together into a paragraph, we can start thinking of that paragraph as a single idea. Then we group logically-related paragraphs into sections. Each section will then contain a single idea, which will effectively summarise the paragraphs within it.

Finally, we group sections together to form the overall document. Using this process, every document will be structured to support a single idea that summarises your final set of groupings.

Why can’t we think top-down?

It is possible to think in a top-down way. Minto actually suggests always trying top-down first because once you’ve worked out what “question” you are trying to answer at the top, the rest falls into place relatively easily.

But often our thinking won’t be developed enough to work out the top part of the pyramid, and we have to start somewhere else. Using the pyramid principle, you can start anywhere in the pyramid and discover all other relevant ideas.

Clear writing should follow a top-down structure

Reading is difficult. A reader needs to recognise and interpret the words they see, work out what the relationship is between them, and then comprehend the significance. Even a short, 2-page document will contain roughly 100 sentences. The mind automatically imposes order on everything it takes in, so a reader will have to hold those 100 sentences together somehow. They will find this task much easier if the ideas come pre-sorted and structured.

Good writing strips away any irrelevant points and presents only the relevant ones in a logical order that helps the reader reach the writer’s conclusion.

Bad writing just puts down all the points—relevant or irrelevant—and leaves the reader to sort through them. It also risks leaving out relevant points because it’s hard to check that your thinking is complete until you’ve imposed a logical order on your ideas.

… [Y]ou cannot tell that nonsense is being written unless you first impose a structure on it. It is the imposition of the structure that permits you to see flaws and omissions

Bad writing is easier for the author, but it’s harder for readers and wastes their time.

The good news is that it’s easier to improve your writing by improving the logical order of your documents than by changing your writing style. Weaknesses of style are hard to change in adults, but writing that follows a logical structure will be easier to follow even if the sentences themselves are not particularly well-written.

What is the pyramid principle?

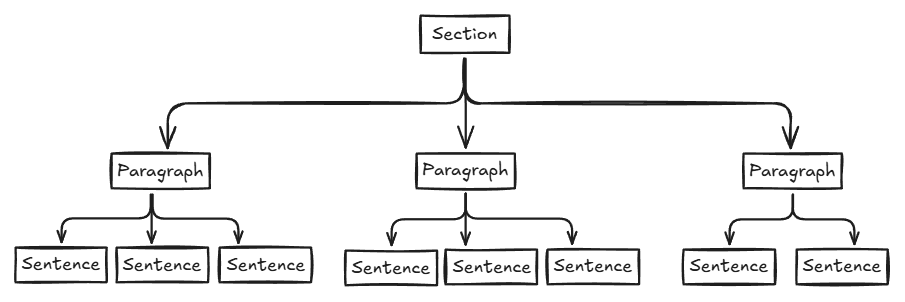

The pyramid structure gives us a way to visualise how different ideas relate to each other. There are three relationships between ideas in a pyramid:

- Down. An idea above a grouping summarises the ideas below it.

- Up. The ideas in the grouping below explain or defend the point above.

- Horizontally. Ideas at the same level sit alongside each other, in logical order.

These three relationships give us the following three rules:

Three rules for building a pyramid

- Ideas at any level in the pyramid must always be summaries of the ideas grouped below them.

- Ideas in each grouping must always be the same kind of idea and described by the same plural noun. That is, ideas have to be at the same level of abstraction to be grouped together. For example, you can’t group apples and chairs together if your level of abstraction is “fruit”, but you can if your level of abstraction is “things”.

- Ideas in each grouping must be logically ordered. There are four logical ways to order a set of ideas (deductively, chronologically, structurally or comparatively), which are explained below.

If you break any of these rules, there may be a flaw in your thinking and the relationships between the ideas may not be clear to your reader. So you should try to restructure your ideas.

This [single idea at the top] should be the major point you want to make, and all the ideas grouped underneath — provided you have built the structure properly — will serve to explain or defend that point in ever greater detail.

This pyramid structure aids your readers’ comprehension in several ways:

- It keeps the reader’s attention by carefully controlling the sequence of ideas;

- It helps the reader keep things in their working memory and see the same logical groupings you do; and

- The reader can skim through the sections less relevant to them.

All of this makes it easier for the reader to understand your argument, which leaves them more energy to consider the significance of what you’re saying.

Control the sequence of ideas

Written text only lets us present one idea at a time. Readers will therefore assume that ideas presented next to each other logically belong together. The single most important act to clear writing is to control the sequence in which you present ideas.

If a person’s writing is unclear, it is most likely because the ordering of the ideas conflicts with the capability of the reader’s mind to process them.

Each idea you state will raise a question in the reader’s mind, so you want to present information to the reader as they need it. To keep the reader’s attention, try not to raise questions before you are ready to answer them (and not answer questions before you have raised them). In this way, you can carry on a question/answer dialogue with your reader through your writing.

Example: Why pigs should be kept as pets

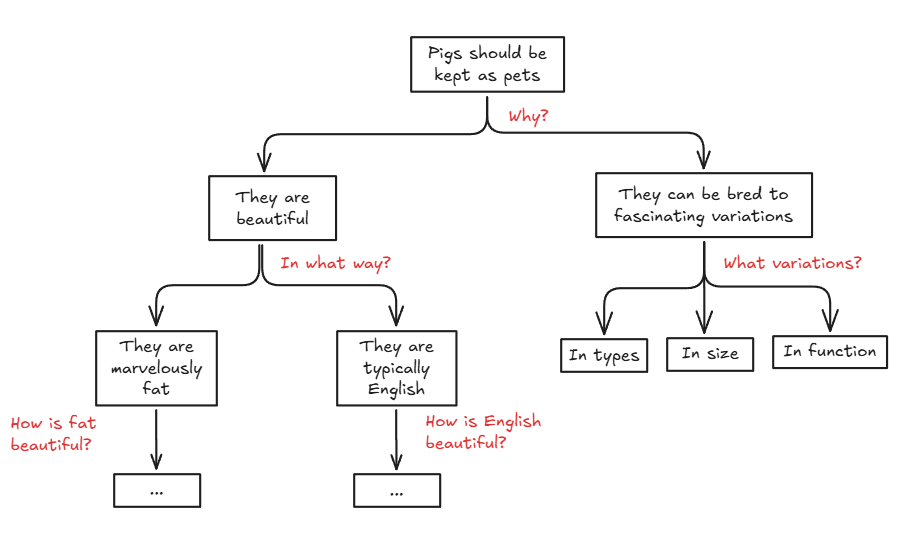

Minto refers to a writing example, the main point of which is that pigs should be kept as pets. This raises the question in the reader’s mind, “Why?”

The author then sets out two reasons:

- They are beautiful; and

- They could be bred to fascinating variations.

The questions now raised are: “How are pigs beautiful?” and “How can they be bred to fascinating variations?” The author should then seek to answer these questions and, in doing so, will raise further questions in their reader’s mind.

Writing that forces your reader to keep going back and forth to make connections is “simply bad manners”. If you want the reader to understand the groupings the same way you do, you should give them the “summarising idea” at the top of each section before presenting the individual ideas underneath. Otherwise your readers may start making incorrect or unintended connections between your points.

Limited working memory

People can only hold about 7 ideas in their short-term memory. Beyond that, they will form groups of ideas and/or start dropping ideas. As a writer, you should help your readers keep everything together and see the same logical groups you do.

Example: Sorting your shopping list

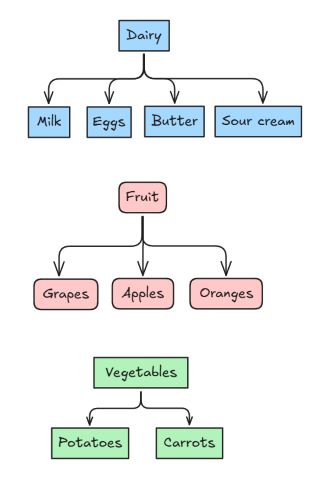

Assume you have to pick up the following 9 items at the store: grapes, milk, potatoes, eggs, carrots, oranges, butter, apples, and sour cream. It is quite difficult to hold all of these in your head at the same time.

Now, let’s sort the items according to the different sections of the supermarket:

You have now moved from a single group of 9 to three sets of 2-4 items, which is much easier to remember.

[Note: more recent research has suggested our working memory may only allow about 4 items, not 7. See A Mind for Numbers on our tendency to “chunk” information to understand it. ]

Allow for skimming

Once you’ve worked out the logical structure of your pyramid, you want to make that structure clear to the reader.

You can do this using:

- Headings. These should be as concise as possible—they should remind, not dominate. People don’t always read headings carefully so don’t depend on them to carry your message.

- Underlined points. Be ruthless in keeping your underlined points short.

- Decimal formatting. Companies and government institutions often use numbers to divide up a document and some will even number every paragraph.

- Indented lists. These can be used in short documents where headings and decimal numbering would not be appropriate.

How to group ideas

How you decide on the groupings within your pyramid structure—which are the major ideas, which are the minor ones, and how they relate to each other—is key.

Groupings must be logical. Our minds naturally create groupings, often outside of our own awareness. For example, you might say that there are “five problems”, but there is actually a whole universe of problems out there. Always ask yourself: ‘Why have I brought together these five particular problems and no others?’ You must clarify the logical link between the ideas.

… you cannot simply group together a set of ideas and assume your reader will understand their significance. Every grouping implies an overall point that reflects the nature of the relationship between the ideas in the grouping. You should first define that relationship for yourself, and then state it for the reader.

When we group ideas together, we use one of four possible analytical processes:

- Deductive;

- Chronological;

- Structural; or

- Comparative.

Which analytical process you use will determine not just the groups you end up with but the order in which you present ideas within the grouping.

Deductive

Deductive reasoning involves reaching a new conclusion from two premises which are related by a logical implication.

For example:

- All men are mortal.

- Socrates is a man.

- Socrates is mortal.

Deductive reasoning contrasts with inductive reasoning, where you notice a similarity between several different things and then group them based on that similarity. In an inductive grouping, you should be able to describe every item with a plural noun (e.g. “reasons”, “problems”, “causes”).

Deductive reasoning is the pattern we follow when problem solving. However, the logic can be difficult for readers to absorb if there is a lot of writing in between each point. Minto therefore recommends pushing deductive reasoning as far down in the pyramid as possible, so that the steps in your argument are right text to each other. At higher levels, you should try to present your message inductively instead.

Example: Presenting an argument deductively vs inductively

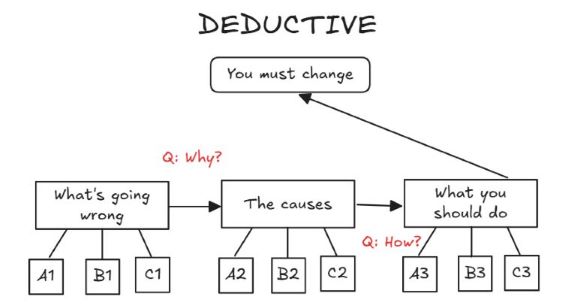

Here’s an example of an argument for change, presented deductively:

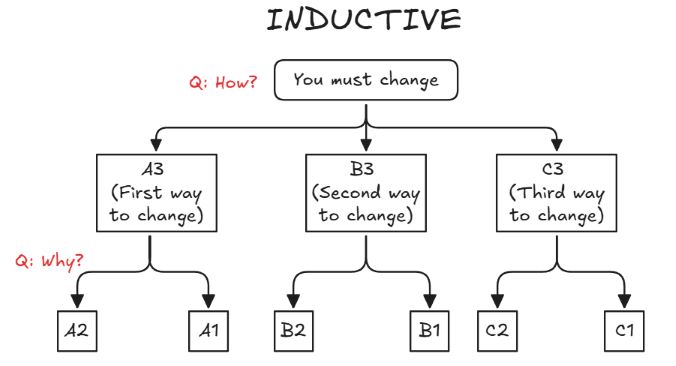

To follow your reasoning, the reader has to remember A1 and then connect it with A2 and later A3 (and the same to match the Bs and Cs). This forces the reader to re-enact your entire problem-solving process before getting to the solution.

It would be easier for everyone to reverse the order and present the solution upfront, and then support it with your deductive arguments at the lower levels.

[This makes sense and works in the rather simple example above. However, I’m not sure all deductive arguments can be presented as inductive ones, particularly if they rely on longer chains of reasoning. In those cases, I think you’ll just have to rely more on recapping along the way.]

It’s almost always better to present the actions before the argument, since that is what the reader ultimately cares about. Two possible exceptions are:

- If the reader is going to strongly disagree with your conclusion, you must do more work preparing them to accept it.

- Where the reader cannot understand the action without an explanation. For example, if you are writing a “How to” paper, the reasoning and argument should go alongside the action.

Chronological

A chronological grouping is appropriate for describing cause-and-effect relationships. Business writing commonly involves prescribing certain steps or recommendations. You should group these action ideas by effect—that is, your summary statement should specify what you expect to happen if the reader takes the steps set out underneath. (Do not group such ideas by similarity!)

Within a grouping, you should present the steps chronologically in the order the reader should take them.

Structural

A structural grouping is used to divide up up a whole into its constituent parts. The most common example is an organisational chart dividing up a company.

When you use a structural grouping, it’s important to ensure that the parts are mutually exclusive (no overlaps) and collectively exhaustive (nothing is left out) (abbreviated as “MECE”).

Comparative

Sometimes you will group items together because of some shared characteristic. [I think this is a grouping formed through inductive reasoning, though Minto doesn’t call it that.] When you do this, you should generally present the ideas in ranked order, by importance or by the extent to which they share the common characteristic.

Your summary statement should then give some insight into why the shared characteristic matters.

Example: Capture the essence of the idea instead of the kind of idea

Say you are discussing problems within a company. Many writers are tempted to just describe the kind of idea that will be discussed (“problems”) in their summary statement.

However, this doesn’t help the reader focus their future thinking, which is the main point of summarising a grouping. Minto recommends instead trying to capture the essence of the ideas themselves in your summary statement. So, rather than flagging “five problems”, you could flag that there are “five problems of insufficient delegation”.

This has several benefits:

- it gives the reader something to think about as they read through the problems;

- it could help you identify more delegation problems; and

- perhaps it could even help you find the solutions.

Presenting your pyramid: the top, middle and bottom

Introduction

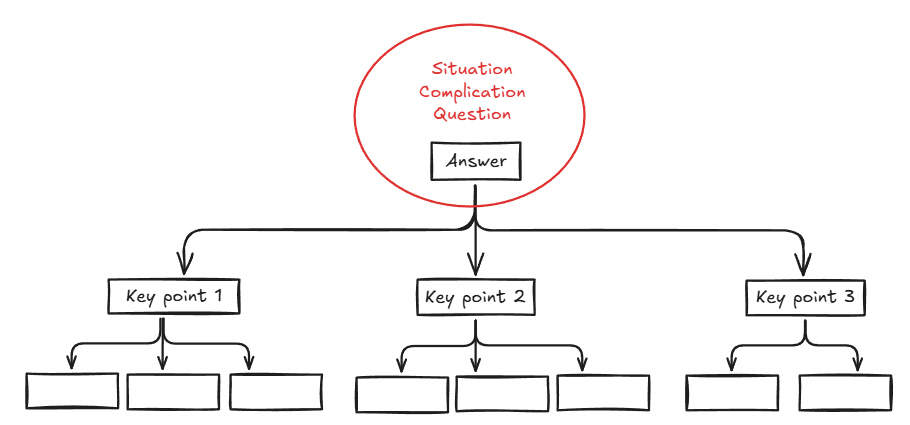

To capture your reader’s attention, you should start by telling a story. A classic story-telling pattern involves 4 elements:

- Situation. This orients the reader by setting out the necessary background, including any historical chronology.

- Complication. This is anything that alters a stable Situation—e.g. a problem, a proposed change, or someone with a different point of view.

- Question. The Complication then raises the Question—e.g. what should we do? Whose view is correct?

- Answer.

The story in your introduction should be one the reader already knows or could be expected to know. Don’t introduce points the reader might argue with at this stage. If someone starts off reading agreeable points, they’ll be more receptive to more controversial ideas later.

These 4 storytelling elements should give you a clear focus for the start of your document. Think of the introduction as a circle around the top of your pyramid that lies outside your structure of ideas. You can rearrange the 4 elements as you wish.

The point of the introduction is to ensure that you and your reader are “standing in the same place” to begin with. This will generally be 2 or 3 paragraphs but could be as short as a sentence, especially if you work closely with your reader (e.g. “In your letter on [date] you asked me …”).

In longer documents, the total introduction should also include a statement of your Main Point and the Key Lines to support that point. The Key Lines should give the Answer to your document’s Question and a sense of what the “plan” of the document looks like. The Key Line Points should be expressed as ideas and could form the headings of your document. This allows the reader to get the gist in 30 seconds or so and be prepared for what the rest of your document will say.

The middle

The middle of your pyramid is where you present your logical groupings. As noted above, the order in which you present ideas at the same horizontal level within each grouping will depend on the analytical process you used to form the grouping (deductive, chronological, structural or comparative).

At the end or beginning of each major grouping, you should pause and recap where you’ve been and where you plan to go next. These transitions should relate what the two groupings say, in a way where you seem to be looking in both directions at once. Ideally, you should be able to pick up the key word or phrase from the previous section and connect it to the major point in the new section. If the previous section was particularly long or complicated, it may be better to stop and summarise completely before starting the new section.

Conclusions

When you are dealing with future actions, you should have a concluding section with the “Next Steps”. The steps you include should follow logically from what you have written—they should not raise any questions you haven’t addressed in the body of your text.

Apart from this situation, Minto does not think conclusions are needed. In theory, if you’ve obeyed the pyramid rules and made all your arguments, you shouldn’t need to conclude. They’re also difficult to do well, so it can be better to omit them altogether.

However, it can be a bit awkward to simply stop writing. If you insist on a conclusion, Minto suggests summing up what you have been saying and leaving the reader with a need and desire to act. That might take the form of a philosophical insight or a prescription for immediate action.

Other Interesting Points

- Minto argues that headings should reflect ideas rather than categories, so you shouldn’t use headings like ‘Background’ or ‘Conclusion’ as they have no scanning value. [I personally disagree. As both a reader and writer, I find these headings very useful. If you don’t know how much background your readers know, it’s helpful to have a clearly marked section to deal with that, which readers can skip over if they want. Besides, these headings are so widespread that readers have come to expect them now when scanning documents.]

- Two tips to put ideas into words:

- Visualise the images you used to think up your ideas in the first place. Images are far more effective at conveying relationships between different things than words are, and we tend to be better at recalling images than words. Once you clearly “see” what you are talking about, you can copy it into words.

- Find the key nouns and look for the relationships between them. This can help cut out the fluff.

My Review of The Pyramid Principle

Minto packs a lot into a rather short book. The Pyramid Principle is fewer than 200 pages, including a fair number of diagrams and examples of both good writing and bad writing (and how to transform the latter into the former). You may find it helpful to read the book for those as some ideas are quite hard to convey without long-ish examples.

My summary has focused on the first half of the book, “Logic in Writing”, which I found to be excellent. I particularly liked its focus on the logical structure. So much writing advice focuses on flair or style, which I think is (1) considerably less important in business writing (where you are trying to sound neutral and bland, not distinctive or evocative); and (2) more subjective and harder to teach.

Unfortunately, I found the second half of the book, “Logic in Thinking”, to be a bit of a slog. I don’t know if it was just me and the examples Minto chose. They might make more sense to someone in management consulting, but I found most of them incredibly dry, which made the ideas difficult to grasp. I also found Minto’s explanations in the second half somewhat confusing. Logic in thinking should precede logic in writing, but I got the impression that Minto doesn’t have a strong handle on formal logic. This is understandable—her background is in management consulting. However, I’d just read The Art of Logic by Eugenia Cheng, who has a mathematics background and gives clearer explanations of abstraction, setting up your logic properly and the limits of logic.

For example, when Minto explains her “mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive” principle, she doesn’t warn her readers that there are things in the real world that perhaps can’t be divided into neat, mutually exclusive categories. Even in a basic org chart, some people may work across different divisions and some teams’ responsibilities may overlap. Cheng, by contrast, explains that logic is binary and when you try to apply it to real life, you may be forced to draw some arbitrary lines in the shades of grey.

With all that said, Minto’s writing advice is still solid and I found it helpful as I struggled with a recent long-ish piece of writing. Just bear in mind that, like all things, implementing Minto’s advice will require some practice. I wouldn’t recommend following her advice slavishly, and you’ll probably have to adapt it somewhat to your own kind of writing. Perhaps the strongest idea in The Pyramid Principle is just to think of your reader. This is pretty common advice, but Minto takes it to another level—reminding you to consider your readers’ working memory limits, to anticipate what questions your statements will stir up, and to control the sequence of your statements accordingly. And, of course, to summarise things for your reader—at the start and (sometimes) at the end 🙂

Let me know what you think of my summary of The Pyramid Principle in the comments below!

Buy The Pyramid Principle at: Amazon <– This is an affiliate link, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through it. Thanks for supporting the site! 🙂

If you enjoyed this summary of The Pyramid Principle, you may also like:

- Book Summary: The Art of Logic by Eugenia Cheng

- Book Summary: A Mind for Numbers by Barbara Oakley

- Book Summary: How to Read a Book by Mortimer Adler and Charles van Doren

4 thoughts on “Book Summary: The Pyramid Principle by Barbara Minto”

Like you, I much preferred the section on writing, and thought it was excellent. I struggled a little bit with the logic in thinking section as well. But I did think the MECE advice is actually a pretty great way to approach problems if you can.

Perhaps ironically, I thought the structure of the whole book (logic in writing, THEN logic in thinking) was maybe not the best. But I assume she did it for a reason.

After I read it I tried to avoid “introduction” “background” sections, etc., but doing that often felt a bit forced. I agree that they can be useful.

Yeah, I can see how MECE would be useful. I just wish she’d taken more time to explain it (including its limitations) perhaps using examples, instead of much of the stuff she did discuss in the second half of the book.

I similarly thought the advice about converting a deductive argument to an inductive one was useful but limited, and also would have benefited from more examples.

Given that you’ve done plenty of writing, how did “Logic in Writing” resonate with you as you were reading it? Did it feel intuitive or similar to your current approach to writing? And how do you think you’ll use the Pyramid Principle going forward?

Good question! Some of it did feel similar to my current approach to writing, though I still found many bits of the advice helpful. I think the Pyramid Principle is strongest for short-ish pieces of writing (probably no more than about 10 pages) that convey one key idea. In such a case, the principle makes a lot of sense and I think you can straightforwardly apply Minto’s advice.

But I think most books are more complex than that and contain more than one key idea, which means you may have to adapt the advice when writing (or summarising) a book. This might also be why, as Phil points out above, the structure of “The Pyramid Principle” itself wasn’t the best – I think Minto was very used to writing pieces of advice, reports, etc which are all relatively short, whereas a book may require more flexibility. The general principles should still apply but you may have to accept your “pyramid” may look slightly misshapen 🙂