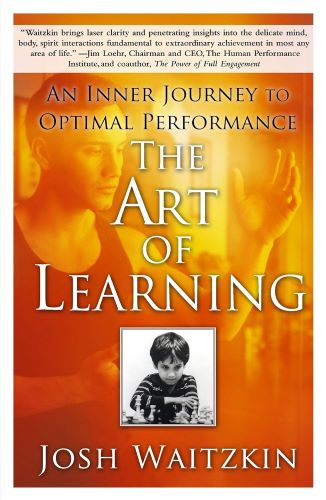

Joshua Waitzkin was a chess prodigy who won 8 National Championships before the age of 20. He later took up Tai Chi and became a world champion within 6 years. His book The Art of Learning is partly a memoir and partly a self-improvement book, explaining the principles that helped him succeed in disciplines as different as chess and martial arts

This summary focuses more on the self-improvement parts, with many examples from Waitzkin’s life. While the book follows a chronological structure, my summary is organised by topic.

Estimated time: 24 mins

Buy The Art of Learning at: Amazon (affiliate link)

Key Takeaways from The Art of Learning

- Mastering the fundamentals will enable you to make new connections:

- Once you’ve learned the fundamentals deeply, you can apply them intuitively. To the untrained eye, your actions will look almost mystical.

- When learning chess, Waitzkin focused on endgames instead of starting positions, which gave him a richer understanding of each piece’s value.

- When learning Tai Chi, Waitzkin would break down a single throw into its components, and practise it hundreds or even thousands of times.

- Learning (and life) involves balance in many areas, such as:

- Conscious vs Unconscious. Your conscious mind provides focus and precision, but can only take in so much information at one time.

- Stretch vs Recovery. Push yourself to your limits, but not past them.

- Process vs Results. Find joy in the process, but still use results for motivation.

- Winning vs Losing. Win often enough to maintain confidence but lose often enough to maintain humility.

- Mental resilience is critical for performing at a world-class level. Building such resilience requires learning to:

- Be at peace with imperfection. Conditions will never be perfect, so you must learn to cope with them.

- Use adversity. Adversity can sometimes spur us to a higher level of clarity and performance.

- Create inspiring conditions internally. Find ways to reach that higher level of clarity and performance even without externally inspiring conditions.

Detailed Summary of The Art of Learning

About Waitzkin

Waitzkin had competed in chess at an elite level since he was a child. Between the ages of 9 and 17, he was the top-ranked player for his age in the US. He won 8 National Championships and represented America in 6 World Championships.

The book Searching for Bobby Fischer was written by Waitzkin’s father and based on Waitzkin’s early life. In 1993, when Waitzkin was 15, a film based on that book came out. Waitzkin soon became a bit of a celebrity. Although he admits enjoying the attention, it worsened his chess game and caused him to dread tournaments. He took some time off in Europe, during which he became interested in Taoist philosophy.

After Waitzkin returned to America, he began practising Tai Chi for its mental and meditative benefits. Later, he moved onto the martial arts side and began training taking Push Hands classes. By the time he wrote The Art of Learning, he had won 13 Push Hands national championships and a world championship.

Though chess and martial arts would seem to have little in common with each other, Waitzkin was able to apply some of the same learning principles to both.

Fundamentals

Becoming an expert requires true mastery of the fundamentals. But experts rarely speak of the fundamentals because that stuff has long become second nature to them—a pianist who consciously thinks about what notes to play will perform worse.

Waitzkin favours depth over breadth, and took this approach in both chess and Tai Chi.

It is rarely a mysterious technique that drives us to the top, but rather a profound mastery of what may well be a basic skill set. Depth beats breadth any day of the week, because it opens a channel for the intangible, unconscious, creative components of our hidden potential.

Example: Learning chess principles by studying endgames

Most chess players start by memorising chess openings. There are many traps and landmines in this part of the game that can force a win or loss, so a player who knows these traps can win quite easily.

The problem with learning openings is that there are too many directions the game can go. You could spend a lifetime memorising the Encyclopaedia of Chess Openings without ever understanding the game. Children who learn chess by memorising openings can initially excel thanks to good genes. But they struggle when they reach higher levels and start losing games.

When Waitzkin learned chess, his teacher spent hundreds of hours with him studying endgames, where the board is nearly empty. Studying these less complex board states made it easier to remember how each piece moved and helped him learn the deeper principles behind the game (e.g. the principle of opposition, the potency of hidden space, etc). Over time, he also developed an intuitive feel for the power of the different pieces and the subtleties of each.

As games got harder, other kids struggled, while Waitzkin grew stronger. Because his expertise was built from the foundation up, he had an advantage when the board was wild and chaotic.

Learning is like building a pyramid with many different levels. Many people stop once they’ve made a discovery and sit around waiting for insight to strike again. Waitzkin, however, seeks a deeper understanding of each discovery. There’ll usually be some connection between the discovery and what you already know and you should try to understand it—figure out its technical components, break it down, study the tapes, and work out all the ways to use your new discovery. After you’ve solidified that level, you can access new knowledge at higher levels.

Balance

Conscious vs Unconscious (Intuition)

Your conscious mind provides a level of focus and precision, but can only take in so much information at a time and needs to take breaks. When you learn some principles and techniques so deeply that your unconscious mind can handle them intuitively, it frees up your conscious mind to focus on other things.

Intuition acts as the bridge between our unconscious and conscious minds and is incredibly important. We shouldn’t treat it as some mystical thing we have no control, nor should we dismiss it just because we don’t fully understand it.

Everyone at a high level has a huge amount of chess understanding, and much of what separates the great from the very good is deep presence, relaxation of the conscious mind, which allows the unconscious to flow unhindered.

Much of what we call intuition involves “chunking”. This usually requires breaking something down into its most basic parts and mastering each of those parts, before putting them back together. Information that has been successfully “chunked” can then be accessed as if it were a single piece of information. [See A Mind for Numbers for a more detailed explanation.]

Example: Learning a judo throw

One of Waitzkin’s favourite judo techniques is a variation of a sacrifice throw (sutemi-waza). When he first saw it, it just looked like a blur to him. To an untrained observer, a master’s movements can appear mystical because there is just too much new information to take in at once.

Waitzkin decided to learn this throw very deeply. So he asked his teacher to break the throw down into its different steps and worked on each one slowly and repeatedly. After mastering each step, he’d put them together.

Today, the throw is his “bread and butter”. Waitzkin’s practised it thousands of times and can perform it perfectly without thinking. This leaves his conscious mind free to focus on other things, like his opponent’s movements.

Stretch vs Recovery

Push yourself to your limits, but not past them. Muscles and minds need to stretch to grow, but will snap if stretched too thin.

Example: Learning to recover during adult chess tournaments

When Waitzkin started competing in adult chess tournaments, he didn’t know how to perform consistently during the longer tournaments. His father signed him up for a performance training centre run by Jim Loehr (who wrote The Power of Full Engagement), where he learned about the importance of balancing stretch (or stress) with recovery and the connection between physical conditioning and mental performance.

Immediately afterwards, Waitzkin began to relax a little while waiting for his opponents to make their move. Sometimes he’d even get up and drink some water, wash his face or sprint up and down some stairs.

Incorporate stress and recovery into all aspects of your life. For example, if you’re reading a book and starting to lose focus, you could put it down, take some deep breaths, and then resume. If you’re running out of steam at work, washing your face could make you feel refreshed. Meditation practice can also help.

Recovery is a skill like anything else. The more you practise, the better you can get at it. Even if you have just seconds to recover in the middle of a competition, you’ll perform better if you can access a tiny haven for renewal in that time. Learning to relax under pressure can also help unlock the potential of your unconscious mind.

You should also balance recovery over longer timescales. During some periods of your life, you’ll be geared up and ready for action. At other times, you might be soft and going through a vulnerable period of growth. If you’re going through a growth phase, make sure to allow yourself some protected space for the growth to occur.

Process vs Results

The path to mastery will contain many challenges and setbacks along the way. Whether someone rises to the challenge or quits is partly determined by the theory of intelligence they hold:

- Entity theorists tend to attribute success or failure to their ingrained or fixed level of ability. When faced with difficulties, they are more likely to quit.

- Incremental theorists are more likely to attribute success or failure to hard work. These people are more likely to rise to difficult challenges.

[I’ve more commonly heard this described as “fixed” vs “growth” mindsets, popularised by Carol Dweck’s book Mindset, but I’ve used the terms Waitzkin uses. Note that there has been some criticisms of Dweck’s work and questions around whether the results replicate. But there have also been responses to that criticism, and Waitzkin’s advice in this book has more nuance than “fixed mindset is bad”.]

Studies show that parents and teachers can influence which theory a child is more likely to adopt, at least in a given situation. Raw intelligence seems to make little difference to whether someone rises to a challenge. Waitzkin’s worked with plenty of talented young chess players and noticed that some of the most gifted players had the hardest time recovering from losses, because they felt the need to live up to some perfectionist standard.

Example: Losing his first national chess championship

When Waitzkin was 8, he narrowly lost his first national chess championship and fell apart. Over the summer, he grappled with many questions like: Am I a loser? Had I let my parents down? how could I have lost? Is there more to life than winning?

“It might sound absurd, but I believe that year, from eight to nine, was the defining period of my life.”—Joshua Waitzkin

In the end, Waitzkin recovered and came back with a renewed commitment to chess. This commitment went deeper than before, when he had seen chess as being just about “fun and glory”.

While it’s important to be able to find joy in the process and learn from losses, this doesn’t mean you should ignore results. Many people take some version of the “process-first” philosophy and use it as an excuse to never put themselves on the line. Some parents similarly shield their children from wins and losses and tell them the results don’t matter.

However, short-term goals can be useful development tools if they are balanced with a nurturing long-term philosophy. It’s okay to enjoy a win when you have worked hard and succeeded at something. It’s also okay to feel sad and disappointed when you lose, and to try and understand why. Losses are valuable learning opportunities, but you won’t learn anything if you don’t try your hardest.

In my experience, successful people shoot for the stars, put their hearts on the line in every battle, and ultimately discover that the lessons learned from the pursuit of excellence mean much more than the immediate trophies and glory.

Winning vs Losing

Waitzkin and his father always searched for chess opponents who were stronger than him, but not too much stronger. This allowed him to win often enough to maintain confidence but lose often enough to learn and maintain humility.

Growth requires loss. Waitzkin’s Tai Chi master, William Chen, called this “investment in loss”. You want to look out for consistent themes in your errors and avoid making similar ones in the future. Some of Waitzkin’s fellow students couldn’t improve because they would try to justify themselves whenever the master pointed out their errors—their need to be correct prevented their learning.

Example: Getting smashed around by Evan

When Waitzkin began learning Push Hands, he spent months getting smashed around by one of his classmates, Evan. He admits it was not easy to “invest in loss” during this time.

After a while, however, he got used to taking shots from Evan and stopped fearing the impact. He learned to become more relaxed when Evan attacked him. As this happened, Evan’s movements seemed to “slow down” in Waitzkin’s mind, and he started to sense his attack before it began. One day, Waitzkin managed to turn the tables on Evan and throw him onto the floor.

It’s not too hard to maintain a beginner’s mind and invest in loss when you are truly a beginner. It gets much harder to maintain that humility and openness when people expect you to perform. But continued growth requires periods where you won’t be in a peak performance state. You have to make that space for yourself, even if the rest of the world doesn’t understand.

I have long believed that if a student of virtually any discipline could avoid ever repeating the same mistake twice—both technical and psychological—he or she would skyrocket to the top of their field.

Building resilience

Mental resilience is arguably the most critical trait when performing at a world-class level, when the difference between winning and losing can be tiny.

Waitzkin sets out three steps to building such resilience:

- Be at peace with imperfection and distraction.

- Use the imperfection to your advantage.

- Create inspiring conditions internally.

An ancient Indian parable

A man wants to walk across the land, but the earth is covered with thorns. He has two options:

- Pave the road and tame all of nature into compliance.

- Make sandals.

Making sandals doesn’t rely on a submissive world or overpowering force. It is the internal solution.

1. Be at peace with imperfection

Practice in imperfect conditions

If you can only concentrate when circumstances are cooperative and calm, you’re like a dry twig that snaps as soon as a distraction hits. If you can integrate distractions into your thinking, you can perform even when the world doesn’t cooperate.

Example: Coping with catchy tunes

Waitzkin started to transition to adult chess tournaments when he was 10. Adult chess matches tended to last longer—sometimes up to 8 hours—and he’d struggle to concentrate for such long periods.

A major problem was that catchy songs would enter his mind and disrupt his concentration. The more he tried to block out the tune, the louder it would get. He’d even start being bothered by sounds he’d never noticed before.

He had a breakthrough one day when he realised he could think to the beat of the song in his head. From that point, he would study chess with the music on several times a week—sometimes music he liked, sometimes music he didn’t like.

This ability to think with distractions also came in handy when he encountered opponents that tried to throw off his concentration with psychological tricks, like tapping chess pieces on the side of the table.

We must be prepared for imperfection. If we rely on having no nerves, on not being thrown off by a big miss, or on the exact replication of a certain mindset, then when the pressure is high enough, or when the pain is too piercing to ignore, our ideal state will shatter.

Recognise and recover from mistakes

One mistake by itself will rarely be disastrous. An actor can miss a line but improvise their way back without the audience even noticing.

But after making a mistake, it can be tempting to cling to the emotional comfort of what the situation was, rather than what it now is. If you don’t recognise that the situation has now changed, the mistake can cause you to enter a downward spiral of more and more mistakes.

2. Using adversity

Increased perception in life-or-death moments

We seem to have a survival mechanism that intensifies our physical and mental capacities in life-or-death moments. Time seems to slow down as we attain a level of clarity and perception we cannot usually reach.

Waitzkin first experienced this in 1993, in an earthquake during the middle of a chess match. Years later, he again reached this state when he broke his hand during a Tai Chi match.

Example: Flow during an earthquake

When Waitzkin was 16, he participated at the World Junior Chess Championship in India. Around 3 hours into a match against the prevailing world champion, he finally reached a state of flow:

“It is a strange feeling. First you are a person looking at a chessboard. You calculate through the various alternatives, the mind gaining speed as it pores through the complexities, until consciousness of one’s separation from the position ebbs away and what remains is the sensation of being inside the energetic chess flow. Then the mind moves with the speed of an electrical current, complex problems are breezed through with an intuitive clarity, you get deeper and deeper into the soul of the chess position, time falls away, the concept of “I” is gone, all that exists is blissful engagement, pure presence, absolute flow.”—Joshua Waitzkin

Then there was an earthquake. Literally. The lights went out and people ran out of the building. Waitzkin was aware of the shaking around him but remained sitting, still in his flow state. He solved the chess problem. Somehow, the earthquake had spurred the revelation.

This feeling of heightened perception is similar to what happens when you master something and can do it intuitively. Time feels slowed because your conscious mind blocks everything out and focuses on a very narrow area. The difference is that when you’ve mastered something, the surrounding information has been integrated into your unconscious through practice while in life-or-death situations, the surrounding information is just ignored. That’s why our minds rarely go to that state of heightened perception—in most situations, we need to be aware of what is happening around us.

Getting out of your mental rut

When you train consistently, you can settle into a “mental rut”. Injuries and other setbacks can force you to become creative. You can also deliberately jolt yourself out of a rut by artificially handicapping yourself or training your weaker side for a few months.

If Waitzkin had stopped training Tai Chi whenever something hurt, he’d spend the whole year on the couch. Even though your body does need time to heal, you can take those as opportunities to develop the more mental aspects of your sport.

Example: Training with a broken hand

Waitzkin broke his right hand 7 weeks before the Tai Chi National Championships. The doctor had said there was no chance he could compete. Waitzkin ignored this and resumed training as soon as he had a cast.

He wasn’t silly enough to use his broken hand. Instead, he trained things like visualisation, perception, timing, and controlling his opponent’s breath patterns. The internal skills are important in Tai Chi but often get neglected in normal training.

Waitzkin also spent time working on his weaker left side. Since his right arm was out of play, he found himself instinctively using his left arm to neutralise both of his opponents’ arms. This injury ended up being a tremendous source of inspiration. After he’d recovered, the techniques he’d learned to control two of his opponents’ limbs with one allowed him to use his free arm for easy pickings. (This principle is also relevant in chess, legal battles, and many other clashes—you gain an advantage whenever you can tie down your opponent with more resources than you are expending to tie it down.)

Finally, though he wasn’t sure it would work, Waitzkin did some intense visualisation practices to try and stop his right arm from atrophying in its cast. When his cast came off four days before the National Championships, his right arm had hardly atrophied. The doctor cleared him to compete, and Waitzkin ended up winning the Nationals.

There are clear differences between what it takes to become decent, good, great, or among the best. If you’re not aiming to be the best, there’s a lot of room for error. You can treat injuries as setbacks and take time off to recover for them. But if you want to be the best, you have to take greater risks and optimise the learning potential of setbacks.

You should always come off an injury or a loss better than when you went down.

Dealing with emotions

Various emotions can crop up during competitions. Different people have their own ways of dealing with them. Waitzkin focuses on anger and explains how he learned to harness it.

Example: Dealing with anger in competitions

In chess tournaments, Waitzkin would get angry if his opponents acted inappropriately or outright cheated. He would try to block out his anger, but some opponents would just escalate until he had a meltdown.

It wasn’t until he was well into his martial arts career that Waitzkin learned how to channel his anger. At the finals of his first Push Hands National Championship, his opponent got away with two blatantly illegal moves. Waitzkin won anyway, but he noticed he had been thrown off by the cheating and reacted too aggressively, and could easily have lost the match.

Over the next year, Waitzkin deliberately sought out dirty players and practised staying in control. After a while, his anger stopped being disorienting and started being motivating. He learned to perform better against dirty competitors than against clean ones. Interestingly, he also found that his opponents would themselves get worked up and angry if their dirty tricks didn’t get into his head.

Once you get comfortable with anger, channelling it into a state of deeper focus isn’t so hard, because we’ve evolved to be sharpest when in danger. It’s just that our lives are relatively sheltered, so we don’t reach that emotional state very often and don’t know how to channel it when we do.

3. Create inspiring conditions internally

Of course, you don’t want to rely on an earthquake or broken hand for inspiration. You want to find other ways to get to moments of real clarity and focus, even when the external conditions are not inspiring.

Waitzkin therefore developed a routine to achieve a serene and focused mental state before matches.

Example: Routine to trigger a performance state

Waitzkin describes how he helped develop a pre-performance routine for a client, Dennis. First, he looked for an activity that got Dennis closest to a state of serene focus—this was playing catch with his son.

Next, they added other things in the lead-up to that activity to make it into a routine:

- Eat a light consistent snack

- 15 minutes of meditation

- 10 minutes of stretching

- 10 minutes listening to Bob Dylan

- Playing catch

Dennis went through this routine every day for a month. After he had internalised this routine, he tried doing the first four steps before an important meeting. The idea was that the routine would trigger the state of serene focus even without the last step.

Dennis raved about his success—he found himself in a totally serene state going into a normally stressful environment, and had no trouble being fully present throughout the meeting.

Once you’ve developed and internalised a routine, you should alter it incrementally so that it becomes lower-maintenance and more flexible. Since you won’t always have the luxury of 30 to 45 mins to get into a peak performance state, you want to pare down the routine without losing the performance benefits. Ideally, you’ll be able to reach a focused state in just a few minutes, or even a single inhalation.

Other Interesting Points

- When Waitzkin played cards, he’d deliberately leave his hands unsorted and sort them mentally, to try and build up his mental resilience and tolerance for disorder.

- In chess, the power of each piece depends on the context. For example, bishops are more valuable while working with rooks while knights are better when working with queens.

- In virtually every competitive physical discipline, reading and manipulating footwork is incredibly important because when someone switches their weight from one foot to another, the receiving leg is momentarily stuck.

- Focusing on an opponent’s blinking could give Waitzkin an edge. Most people blink without noticing, and even top competitors don’t think of it as something that can be exploited in a match. But your presence is slightly altered in the middle of a blink, which can give an opening especially if combined with other information.

My Review of The Art of Learning

It was nice seeing the overlaps with other books I’d read on learning and performance, notably A Mind for Numbers and The Power of Full Performance. But those two books are written from the viewpoint of a teacher or coach, so it was interesting to read the perspective of a world-class performer instead. Since Waitzkin is not a scientist or academic, his writing is slightly more “woo” and a lot more personal.

One thing that came through strongly in the book, but which wasn’t addressed explicitly, was the importance of patience—or perhaps dedication. It sounds like he was naturally very passionate about both chess and Tai Chi, and so didn’t mind spending months cultivating a single punch in order to perfect it. He doesn’t really talk about having to sacrifice other hobbies or relationships in his pursuit of excellence, which makes me think he never saw these as difficult trade-offs.

Waitzkin is clearly an intense person who has always been highly driven to be “the best”, and admits as much:

I was an intense competitor, and have never been one to give up on a goal. As a funny aside, my ever-precocious sister started amusing herself with this never-quit aspect of my personality when she was three years old by giving me coconuts to open on Bahamian beaches. I’d spend hours smashing away in the sun, refusing to give up until she was drinking and munching away. In my scholastic chess life I was almost always able to put more energy into the struggle than my opponents. If it was a battle of wills, I won.

I am definitely not wired the same way. If I broke my hand 7 weeks out from a National Championship, I wouldn’t dream of continuing to train for it!

Still, I found The Art of Learning to be an entertaining and useful read. Building mental resilience is worth doing no matter your level of ambition.

Let me know what you think of my summary of The Art of Learning in the comments below!

Buy The Art of Learning at: Amazon <– This is an affiliate link, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through it. Thanks for supporting the site! 🙂

If you enjoyed this summary of The Art of Learning, you may also like:

- Book Summary: The Power of Full Engagement by Jim Loehr and Tony Schwartz

- Book Summary: So Good They Can’t Ignore You by Cal Newport

- Book Summary: Range by David Epstein offers a counterpoint to Waitzkin’s preference for “depth over breadth”.