I learned about A Mind for Numbers when doing Oakley’s excellent (free) online course Learning How to Learn. I did that course several years ago and still retained some important ideas from it – even though I took no notes at the time. Since it’s been a few years now, I thought it was a good time to do a refresher by reading and making a summary for A Mind for Numbers. I wanted to see if there was more to the book that wasn’t in the course.

Oakley doesn’t just give study tips (though it certainly does provide many of those). She also explains why those study tips or strategies work, and supports that with evidence.

Buy A Mind for Numbers at: Amazon | Kobo (affiliate links)

Key Takeaways from A Mind for Numbers

- Active learning is much more effective than passive:

- Reading passively is a bad way to learn. It gives you the illusion of competence, without you taking much information in.

- Similarly, research has shown students learn better when they are actively engaged, compared to listening to someone else speak. Actively learning may involve things like explaining things to others or asking questions.

- We need to switch between our brains’ focused and diffuse modes:

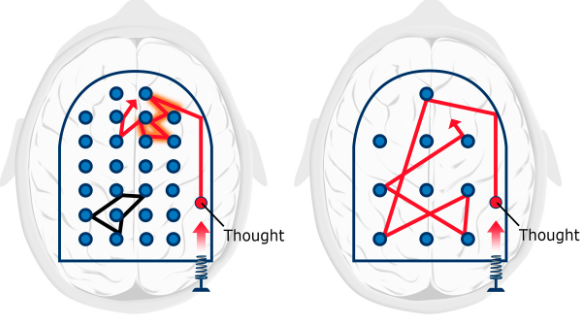

- When we actively focus on a problem, our brains are in focused mode. Some tasks take a lot of focus, but in this mode we can also encounter Einstellung (mental roadblocks).

- The diffuse mode helps us get around Einstellung. Our brains enter the diffuse mode when we’re not focusing on the work at hand. We may be taking a walk, talking to friends, etc. But our brains can still work on the problem and make connections in the background. Often when we take a break and come back to a problem, we can see it from a new angle and overcome Einstellung.

- When you’re working on something particularly hard, it’s helpful to sleep on it and come back to it the next day. The more time you have between focus sessions, the more likely you are to make breakthroughs and see things in new ways.

- When we chunk information, we can free up our working memory:

- Our working memory is limited – it only has 4 slots. To make the most of our working memory, we have to group information into “chunks”.

- Once a chunk is formed, its details are stored in long-term memory instead of our working memory. This frees up our working memory, and we can engage with more ideas at the same time.

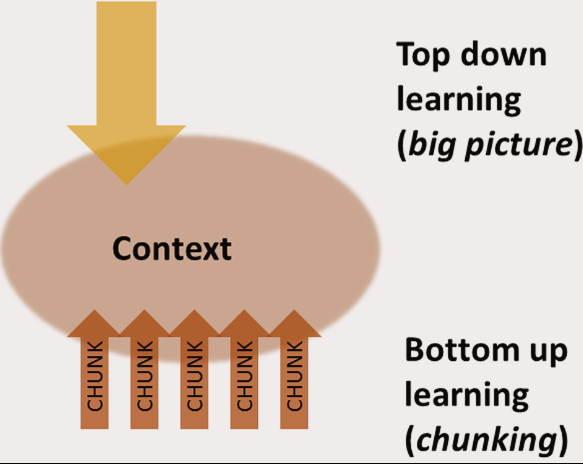

- Chunking involves both top-down and bottom-up learning. The bottom-up part is where you practise and repeat it in different situations. The top-down learning is understanding and seeing the bigger picture. Both are vital to gaining mastery.

- Some effective learning techniques include:

- Test yourself. Testing yourself forces you to try to recall information. It doesn’t matter how you do on the test, the process itself will help you learn.

- Spaced repetition. Review the same material with increasing time gaps in between.

- Skimming ahead. When reading a textbook, skimming ahead to see the chapter headings, tables, diagrams, etc will give you a better sense of how everything hangs together. When taking a test, skimming ahead to the hard questions first before going back to do the easier ones will give your brain more time to work on the hard questions – it can do so in the background in the diffuse mode.

- Simplify things and try to explain them to others. Many complex ideas can be broken down into smaller parts. Often these parts will be similar to something you already understand. When you break something down in this way, your understanding of it becomes a lot stronger.

- Procrastination is really harmful because it reduces the amount of time your brain has to switch between focused and diffuse modes. Some tips to overcome procrastination include:

- Pace yourself. Break up a large task into daily tasks. Review your “to do” list the evening before each day.

- Focus on process, not product. We often procrastinate because the thought of doing something (starting an assignment, studying, etc) is painful. But when we actually start doing it, it’s not that bad. So if you make it your goal just to get started on the process – without putting pressure on yourself to complete the task – it can make the thought less painful.

- Remove or ignore distractions. Try to set yourself up in an environment that is free from distractions. Turn off your phone, turn off email notifications, etc. If you can’t remove them completely, then practise ignoring distractions. A Pomodoro timer can help with this.

Detailed Summary of A Mind for Numbers

Oakley’s background

Oakley herself hated math and science growing up, and flunked through her high school math and science courses. She enlisted in the army right out of high school because they paid her to learn Russian. The army later commissioned her in the US Army Signal Corps, which required her to develop technical knowledge of things like radio and cable systems. Since the job prospects for Russian linguists are … pretty limited, she couldn’t really leave, either.

So Oakley went back to college to get a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering. It was difficult at first, but she found that part of her problem was just that she’d been trying to learn in the wrong way. As she learned how to learn, she got better at math and science.

Oakley also points out that we develop a passion for things we are good at. As she got better at math and science, she enjoyed it more. She went on to get a master’s in electrical and computer engineering, and later a doctorate in systems engineering. It’s a mistake to think that if we aren’t good at something, we do not – and cannot – develop a passion for it. [Will MacAskill similarly argues that advice to “follow your passion” is unhelpful because, among other reasons, interests change over time.]

Focused and Diffuse Modes of Thinking

Our brains frequently switch between the focused mode (a highly attentive state) and a more relaxed diffuse mode (resting state).

Below is a table comparing the focused and diffuse modes:

| Focused Mode | Diffuse Mode |

|---|---|

| Involves brain’s prefrontal cortex | Not affiliated with any particular area of your brain |

| Rational, sequential and analytical | Big picture |

| Used to concentrate on things that are already connected in our minds | Used to form connections and new insights |

| Seems to involve the left side of the brain more | Seems to involve the right side of the brain more |

| Like a pinball machine with bumpers close together – thoughts bounce around in a small space | Like a pinball machine with bumpers far apart – thoughts can travel further |

We need both the focused and diffuse modes

Both focused and diffuse modes are essential for studying math and science. The focus mode uses rational, sequential and analytical approaches. But sometimes we focus too intently and try to solve a problem using thoughts that are in a different part of our mind from where the “solution” is. This is the Einstellung effect.

Einstellung is the German word for “mindset”. The Einstellung effect occurs when an initial thoughts in your mind prevents a better idea or solution from being found – like a mental roadblock. It’s particularly common in science, because our initial intuition is often wrong.

The diffuse mode helps us gain new insights on problems we’ve been struggling with and to see the “big picture”. When we’re trying to understand a new concept or solve a new problem, we don’t have existing neural patterns to help guide our thoughts. If we relax and let our minds wander, we allow different areas of the brain to form new connections. For example, the best language programs, such as those at the Defense Language Institute (where Oakley learnt Russian), combine focused mode (structured practice with plenty of repetition and rote) and diffuse mode (free speech with native speakers).

So the diffuse mode can help our minds think more widely. But we still need to engage the focused mode to cross-check and verify the diffuse mode’s conclusions – intuitive insights aren’t always right! Also you can’t just use this as an excuse to faff around. It’s the shifting back and forth between the two modes that is effective. You can think of it like exercise – you can’t just lift weights constantly. Your muscles need time to rest and grow. But you can’t spend all your time resting, either.

This is based on science

There is research to show that there are differences in the left and right sides of the brain:

- The left side of the brain is more associated with careful, focused attention. It also seems better at handling analytical, sequential and logical thinking. But the left hemisphere tends to be more dogmatic and cling to views it’s already formed.

- The right side of the brain seems to be more tied to diffuse scanning of the environment, interacting with other people, and processing emotions. It’s also linked with big picture processing and stepping back to do “reality checks”. The right hemisphere is like a Devil’s Advocate that looks for global inconsistencies. People with damage to the right hemisphere often cannot gain “aha!” insights.

However, old myths saying that some people are “left-brained” or “right-brained are untrue. People don’t tend to have a stronger left- or right- side of their brain. But it’s important not to throw the baby out with the bathwater and ignore differences between the two sides of the brain.

How to shift between focused and diffuse modes

Shifting happens naturally if you distract yourself and allow time to pass. You could go for a walk, take a nap, do some exercise, take a shower, meditate, or play or listen to music. Sleep is one of the most effective ways to engage your diffuse mode.

Some other options include playing video games, surfing the web, talking to friends, reading a book, watching TV or a movie. However, these activities are best used briefly as rewards, as they engage the focused mode more than the activities in the above paragraph.

Thomas Edison is thought to have used a special trick to shift from the focused mode to the diffuse mode. When he encountered a difficult problem, he’d take a nap on his chair, holding a ball bearing in his hand above a plate on the floor. As he relaxed, his mind moved towards the diffuse mode. But if he fell asleep, the ball bearing would fall onto the plate, causing a loud sound to wake him up. He could then tap into the fragments of those diffuse thoughts. Oakley clarifies that the accuracy of this story is doubted. However, Salvador Dalí also used this technique.

It can take several hours to get your conscious mind completely off the problem you’re working on. But you don’t want to let things go untouched for more than a day, either – you want insights from the diffuse mode to be passed on to your focused mode, and leaving it too long may cause those insights to fade away.

Memory, “chunking” and spaced repetition

Effective learning involves both working memory and long-term memory.

Working memory vs Long-term memory

Working memory is the part of memory that deals with what we are immediately and consciously processing in our minds. Our working memory can only hold around 4 “chunks” of information:

- Researchers used to think it was 7, but that was because we automatically group things into chunks, so our working memory appeared bigger than it actually was.

- It seems that practice may help to expand our working memory. For example, doing exercises to repeat long strings of digits backward seems to improve working memory.

To maintain something in working memory, we have to apply energy to it. Otherwise, our bodies divert energy elsewhere and the information leaves working memory.

Long-term memory is more like a storage warehouse. When an item makes it to long-term memory, it usually stays there. Long-term memory is where we store the fundamental concepts and techniques we use to solve problems in math and science. There is room for billions of items in long-term memory. But it can be hard to retrieve things from it.

“Chunking” information frees up our working memory

“Chunks” are pieces of information bound together through meaning. Unlike rote memorisation, which doesn’t help you understand what’s really going on, chunking makes the bits of information easier to remember, and helps you fit it into the big picture of what you’re learning.

When we create conceptual chunks, our brains can run more efficiently – we can just deal with the main idea without dealing with all the little underlying details. For example, in the morning you might think “I’ll get dressed”, without thinking of all the steps involved in getting dressed. Mastering a technique or concept means it occupies less space in our working memory. Instead of taking up all 4 slots, a chunked idea may only use 1 slot (your long-term memory is used to deal with the details). This frees up our working memory to grapple with other ideas.

This is similar to “muscle memory” in sports. When you begin to learn something like hitting a ball, you have to think about all the things involved. As we practise and repeat it, the act of hitting the ball becomes a single chunk. So we can just focus on one step – one chunk – instead all the steps involved. In fact, focusing on all the little steps causes us to overthink and is more likely to lead to “choking”.

Experts often rely on “intuition”, rather than conscious thinking, when they make complex decisions rapidly. This is relying on the chunks they’ve developed with experience. In contrast, teachers and professors sometimes get too caught up in following the rules – focusing on the steps separately. In one study, participants were shown 6 different people doing CPR. One of these was a professional paramedic. When asked to guess which of the people doing CPR were experts, professional paramedics guessed correctly 90% of the time. CPR instructors only picked out the correct one 30% of the time – they criticised the actual experts for not taking time to stop and measure where to put their hands.

Working memory, intelligence and creativity

High intelligence often means having a larger working memory. But thanks to the Einstellung effect, smarter people are often less creative. If you can hold many ideas in your mind tightly, those ideas can block fresh new thoughts.

In contrast, if you find it hard to focus on stuff – if your focus drifts as you start daydreaming – you may be more creative. You may have to work harder to understand what’s going on and “chunk” it, but once you do, you can deal with that chunk in many creative ways. Since your working memory – which relies on the focusing abilities of the prefrontal context – doesn’t lock everything up as tightly, you can more easily get input from other areas of the brain, such as the sensory cortex. (The sensory cortex is more in tune with the environment, and is the source of dreams and creative ideas.)

How to Build a Chunk

To build a chunk, we need to forget the extraneous. For example, Solomon Shereshevsky had an amazing memory and seemed to be able to recall everything in detail. But because his individual memories were so rich and detailed, he couldn’t filter out the unimportant stuff and bind the important parts together to form chunks.

Steps to building a chunk

- Focus your attention on the information you want to chunk. You’re making new neural patterns and connecting them with pre-existing patterns in your brain.

- Understand the basic idea. Understanding is like a superglue that holds memory traces together. You may be able to create a chunk even if you don’t understand it, but it will be quite useless since it won’t fit in with other material. (And bear in mind that just understanding how a problem was solved doesn’t mean you can call it to mind later – active recall is needed.)

- Gain broader context. Broader context helps you understand when to use the chunk and when not to. This helps with fitting the chunk into the bigger picture, and to apply your knowledge to new problems. You can gain this broader context by repeating and practising it in different situations – this strengthens the connections to your chunk, and builds many different “paths” to it. Skimming ahead to later chapters or lectures can also help gain a sense of the big picture.

Chunking therefore involves both “top-down” and “bottom-up” processes. The “bottom-up” part is the practice and repetition (memorisation is not always bad). The “top-down” part is the big picture and understanding. Context is where the two meet. Both are vital to gaining mastery.

Understanding

Bring abstract concepts to life

One of the most important things in learning math and science is to bring abstract concepts to life in our minds. Almost every concept has an analogy with something you already know. For example, blood vessels are like highways, nuclear reactions are like falling dominoes. These analogies can be very powerful in helping you understand things. You can then build a new, more complex neural structure from an existing neural structure you already have.

Simplify things – break them down

Try to explain something you’ve learned in a simple way so that even a 10-year-old could understand it. Don’t just think it – say it out loud or write it down. Simple explanations are possible for almost any concept, no matter how complex. There’s a Reddit called “explain like I’m five“. Teachers often say the first time they really understood the material was when they had to teach it.

To create a simple explanation, you have to break down complicated material to its key elements. This gives you a deeper understanding of the material – understanding can arise as a consequence of attempts to explain things (rather than before such attempts). [Completely agree with this – it is key to how I learn things. People have told me I’m good at explaining complicated concepts. My “secret” is that I’m pretty slow. Often I don’t understand things straight away (especially if it’s explained to me verbally). I have to take the time to break things down into simple elements, and then put it back together. Once I’ve simplified things enough for me to understand, it’s relatively easy to explain simply. I know other people who seem to be smarter than me and grasp complicated concepts right away – but they generally don’t seem to be so good at explaining things to others.]

Some people may be slower to understand things than others. A slower way of thinking is not always a disadvantage – it can reveal confusing subtleties that others don’t notice. And when the student does get it, their understanding may be deeper than others who picked it up quickly. Unfortunately, some instructors feel threatened by the deceptively simple questions such students may ask and brush them off. If you find yourself in this situation, don’t despair. Reach out to classmates or the Internet to help or, if possible, find another instructor. In the end, it will take however long it takes, but persistence is often more important than intelligence.

Understanding equations

Equations are not just things you plug numbers into to get numbers. Equations tell a story about how the physical world works. The key to understanding an equation is in understanding that story – that is far more important than getting the right numbers.

You should think about what an equation means, and check that your math and your intuition match. If they don’t, you’ve made a mistake in either your math or your intuition.

Sometimes it’s helpful to take limiting cases where one variable or another goes to zero or infinity. That may help you understand what the equation is saying.

[This part about equations is not written by Oakley herself but is taken from an excerpt from Brad Roth of the American Physical Society at the end of one of the chapters. I thought it was the most useful excerpt in the book – the rest largely repeated what Oakley said in some other way.]

Don’t multitask

Multitasking inhibits your ability to learn deeply. Constantly shifting attention is like constantly pulling up a plant – new ideas and concepts have no chance of taking root. Multitasking also makes you tired more quickly – each tiny shift uses up some energy, and these add up. Students who multitask while studying or sitting in class have been found to receive consistently lower grades. [Causation could go the other way around, though. Students who do poorly in school may feel discouraged or less motivated to focus.]

Transfer

Deep understanding helps with transfer. Transfer is when you’ve learned something in one context but can apply it to another context. It’s frequently easier to learn a second foreign language once you’ve already learned one. This is because when you were learning the first language, you also learned generally language-learning skills and potentially new words and grammatical structures that transfer to learning the second language. [This matches my experience. When I was learning a foreign language, a lot of time was spent learning how to learn – discovering what methods worked for me, finding good language-learning resources.]

Mathematicians tend to like teaching math in an abstract way, because they believe that it helps with transfer. They worry that learning math in a discipline-specific approach makes it harder to apply math in flexible and creative ways later. However, it’s often easier to learn an idea if it’s applied directly to a concrete problem, even if that makes transfer harder later on. So there ends up being a constant tussle between concrete and abstract approaches to learning maths. Oakley thinks both concrete and abstract approaches have pros and cons.

Don’t rely on teachers, but do reach out to good ones

People learn best when they are actively engaged in the subject. It’s important to take responsibility for your own learning, as it will help you think independently. Teacher-centred approaches may sometimes foster a sense of helplessness among students – they rely on the teacher for everything, rather than trying to find out answers themselves.

At the same time, sometimes you will come across very good mentors or teachers. You should take these opportunities to reach out and ask them questions. But good teachers and mentors tend to be very busy, so use their time wisely and always show them your appreciation.

Memory retrieval and recall

As mentioned above, there is room for billions of items (including chunks) in long-term memory, but it can be hard to retrieve them. Practising recall is retrieval practice.

When our brains first put something in long-term memory, we need to revisit it a few times to increase the chances we’ll be able to find it later. The more we revisit something, the stronger its neural patterns. This is why spaced-repetition is so helpful. Try to touch again on something you’re learning within a day, then gradually increase the time between “upkeep” repetitions to weeks or months. Spaced-repetition flashcard software like Anki can be very useful. [I’ve used Anki and other spaced-repetition software before for learning languages, and agree that it’s an incredibly effective way of learning new vocab.]

The main challenge with repetition and practise is that it can be boring. [With recall, I think the challenge is also that it’s hard. We don’t like the sense of failure that comes when we try to recall something and fail. We prefer the illusion of competence involved in re-reading.] But practising regularly for short periods, is much more effective than practising infrequently for long bursts.

Improving your memory

We’ve established that it’s important to understand things in order to form chunks. But that’s not to say that memorising facts is unimportant. Key facts often form the seeds for chunks.

The most important part of memorisation similarly involves understanding what the formulas and solution steps really mean. A study of actors memorising their lines showed that they avoid memorising scripts verbatim. Instead, they seek to understand the characters’ needs and motivations to make it easier to remember their lines.

As noted above, spaced repetition is very effective for remembering things. But instead of relying solely on repetition, you can also use techniques that rely on our visual and spatial memory systems. Our visual and spatial memory systems are actually very good, because these systems were required for survival. Human ancestors did not have to memorise many names or numbers, but they did need to remember how to get home after a long hunt.

In a case study, Sheryl Sorby, a 3D graphics designer points out that many people believe that spatial intelligence is something you either have or you don’t. People with high spatial intelligence can imagine what objects will look like from a different angle, or if they’ve been rotated or cut up. Spatial intelligence can also help you with reading a map. Sorby argues that people can actually train their spatial intelligence. Ways to do this include:

- sketching an object, then trying to sketch it from another angle;

- playing 3D computer games;

- putting together 3D puzzles; and

- practise navigating with maps instead of using GPS.

Oakley sets out a bunch of tips that can help improve recall. She anticipates that “purists” might argue such tips are gimmicks that don’t really help learning. However, research has shown that students using these tricks outperform those who don’t, and that such memory tools help people chunk and see the big picture faster. This in turn helps them become experts faster. Moreover, memorisation using the below tips can improve creativity.

Tips to Improve Recall

- Using a memorable image to remember – e.g. the picture of a flying mule could help you remember Newton’s second law, force = mass x acceleration

- If you’re trying to memorise something that is commonly used (e.g. planets in solar system, the carpal bones in the hand), search online to see if others have already come up with a good memory trick for it.

- The memory palace technique. This takes a bit of time and practice to do, but it gets easier and faster the more you do it. A study showed that a person using the memory palace technique could remember more than 95% of a 40-50 item list after only one or two mental “walks”. This technique also forces you to exercise creativity. [I’ve heard of the memory palace a few times but have always found it a bit gimmicky. There are very few occasions where I need to remember lists of 40-50 items.]

- Using visual metaphors – e.g. imagine you’re an electron trying to burrow through a slab of copper, or pretend to be the x in an algebraic equation. [Yeah, not really for me.]

- Associate numbers with a system you’re already familiar with. For example, Oakley likes to associate numbers with the feelings of when she was, or will be, a given age.

- Mnemonics are commonly used in medicine. Often they involve short sentences that create meaning through a short but memorable story.

- Using more areas of the brain while learning. For example, writing something by hand can help you remember it better than typing (Oakley points out there isn’t much research in this area, but many educators believe this to be true). Reading things aloud can also build another hook.

- Use recall. After reading a page or chapter, look away and try to recall the main ideas. Trying to recall material when you’re outside your usual place of study can also help strengthen it by viewing it from a different perspective. You learn to become independent of cues from a particular location.

- Test yourself often. Testing is not just a way to measure what you know – it’s also a powerful learning tool. It strengthens the neural patterns in your brain. It’s effective even if your test performance is bad, and even if you get no feedback! (You’ll do better of course if you do have feedback and can check your answers.)

- Try to explain what you’ve been learning to a friend or family member. Being forced to simplify something to others without your background can be surprisingly helpful to building your understanding.

- Exercise can also help. Regular exercise seems to improve memory and learning. If you’re struggling to recall something, a little physical exertion (e.g. pushups, jumping jacks) can surprisingly impact your ability to recall.

Illusion of competence

Some common study techniques give off an illusion of competence:

- Passive re-reading. It’s not an effective way of studying. But it’s easy to do, which is why students persist in it. The only time it seems to be effective is when you let time pass in between, so that it becomes a spaced repetition exercise.

- Highlighting and underlining. Marking up text can fool us into thinking we’ve placed the concept in our brain. Keep highlighting and underlining to a minimum – just one sentence or less per paragraph. Instead, try to write notes in the margin that synthesise key concepts.

- Looking at the solution before you’ve worked through it. It can be tempting to just look at a solution and think you understand how to do it. [Totally guilty of this myself when I’ve felt lazy.]

- Concept maps. Studies have also shown that practising and recalling material is much more effective than concept maps. (However, concept maps can be useful when the student is forced to engage in recall when deciding what to put on the map. Some topics also inherently lend themselves to “concept map” approaches.) [I have a special hatred for concept maps (or mind maps as we called them), because of a high school teacher that forced us to do them even when they were, in my opinion, unnecessary and inappropriate. But even I have to admit that they can be very useful when used properly.]

Don’t overlearn, do interleave

Overlearning can be a waste of valuable time. Overlearning is when you continue the study or practice of something even after you understand it well. Textbooks sometimes encourage this by putting problems of the same type together. After the first couple of problems, you’re no longer thinking, but just repeating what you did in the previous problem.

In contrast, interleaving is when you practise a mixture of different problems requiring different strategies. Once you have the basic idea, start interleaving. [This is probably one reason why doing practise problems from past tests and exams is often more effective than practising from the textbook. Tests and exams will naturally involve a mixture of problems.]

Procrastination

Procrastination is a keystone bad habit that influences many important areas of your life. Overcoming procrastination can therefore lead to many positive changes. You may be able to procrastinate and get away with it sometimes, but as you go higher in math and science, it can bite you in the butt.

Procrastination is harmful in a number of ways:

- It doesn’t leave you enough time to engage the diffuse mode. If you procrastinate too much, you won’t have enough time to consolidate neural structures in your long-term memory.

- Procrastination can be stressful because it puts pressure on you to understand things quickly. Learning is a lot more enjoyable when you allow yourself time to digest things. Procrastinators report higher stress, worse health and lower grades.

But procrastination isn’t all bad. Pausing and reflecting, and prioritising, are healthy forms of procrastination. When math experts (professors and graduate students) and math novices (undergraduate students) solve physics problems, the experts are actually slower to start solving a problem. Additionally, when you’re struggling with a problem, it’s important not to get frustrated or dismiss the problem as being “too difficult”.

Why we procrastinate

We procrastinate things that make us feel uncomfortable. There are studies to show that when a mathphobe thinks about working on math, the pain centres in their brain light up. They may then procrastinate by shifting their focus to something more enjoyable, causing them to temporarily feel better. Procrastination is like addiction in that it offers temporary excitement and relief, but has negative effects in the long run.

The key point, however, is that it’s the anticipation of something we dislike that is painful. When the mathphobes actually did math, the pain disappeared. We spend more time and energy dreading a task than actually doing it.

Overcome procrastination by building better habits

Willpower is a limited and precious resource. Try to avoid using willpower to beat procrastination unless absolutely necessary. A better way to tackle procrastination is by building new habits to replace the procrastination habit (this still involves some willpower, but not a lot).

A habit is when our brain launches into a preprogrammed “zombie” mode. Habits save us energy – by going into “zombie” mode, we free up our focus for other things. (This is a bit like how chunking frees up working memory – chunking is actually closely related to habits.)

Habits involve 4 parts:

- The Cue. A cue is a trigger that launches our “zombie” mode. For example, it can be a location, time, how you feel, or something that just happened.

- The Routine. This is what we do when we’re in zombie mode. Our zombie responses can be helpful, harmful, or neutral.

- The Reward. We develop a habit because we get some reward from it. With procrastination, the reward is the mind’s focus to something that is more pleasant and less painful. It’s an easy habit to develop because the reward happens so quickly. To develop a new habit, you have to substitute in a different reward. It could be an emotional payoff – e.g. a feeling of pride for getting something done. Or it could be more concrete – e.g. being able to watch a TV show guilt-free, having dessert.

- The Belief. To change a habit, you need to believe that you can do it. One approach is mental contrasting. [Annie Duke discusses mental contrasting in more detail in How to Decide.]

To overwrite a habit, you need to change your reaction to a cue. This is the only place you need to apply willpower. You can also develop reactions to new cues – e.g. start homework as soon as you get home.

With procrastination, you first need to identify what triggers it. This can be hard – procrastination is so automatic, you may not be aware you’ve even begun to procrastinate. It may be helpful to keep notes on yourself – what you complete and don’t complete, what your cues might be and your responses to those cues, etc. You will then have a better sense of your behaviour and can do self-experiments to see what works and doesn’t work for you.

It may take about 3 months to get in place a new set of working habits you like and are comfortable with. Try to phase changes in – making drastic changes immediately may not be sustainable and could just discourage you more.

Focus on Process, not Product

The product is an outcome – e.g. an essay you need to write, homework problems you need to solve. Whereas the process is just the time and actions you spend working towards that product.

Focusing on the product often triggers the pain that makes us procrastinate. If you focus instead on the process, you can get closer to the goal without the pain. For example, instead of saying “I will write a blog post today” (which can feel daunting), just say “I will write for 25 minutes today” (which feels more achievable). [This is probably the most useful thing I took away from Seth Godin’s The Practice.]

Oakley recommends trying the Pomodoro technique. This involves setting a timer for 25 minutes, and concentrate on your work for that time. Twenty-five minutes is a short enough time that most people can focus their attention for that long. You might find it stressful being “on the clock”, but researchers have found that mild stress can help us perform better in more stressful situations (e.g. tests and exams).

Pace yourself

Learning with regular periods of relaxation between times of focused attention is more fun and also allows us to learn more deeply.

Once a week, write list of tasks you can reasonably work on or accomplish. Then, every evening, write a daily task list of what you’ll do the next day. Oakley suggests doing this in a planner-journal.

Advantages of doing this include:

- Break up big tasks with distant deadlines into small tasks that show up on your daily list. You can then tackle them bit by bit.

- Doing a daily list the evening before helps your subconscious grapple with the things on the list.

- Getting your to-do list down on paper frees up your working memory. Instead of remembering 5 tasks, you can just remember 1 – to check your planner-journal! [Instead of a planner-journal, I use Todoist. I’ve certainly found it helps with anxiety as I no longer have to worry about important tasks falling through the cracks.]

- It’s important to plan your quitting time and make room for relaxation. Your planner-journal can reveal if you consistently work beyond your planned quitting time, or don’t finish the tasks you’d hoped to accomplish. It’s common to be too ambitious when you first use a task list. You can then make adjustments in your strategy to fix it.

Sometimes inspiration hits. You may be super productive and get a lot done, working late into the night. However, if you look at your planner-journal, you’ll probably be less productive in the following days. People who get heir work done in binges tend to be much less productive overall than those who work in reasonable, limited stints. Work binges can lead to burnout. Moreover, relying on adrenaline is dangerous because too much stress can impede your ability to think clearly.

More tips to overcome procrastination

- Change up your environment to make desirable behaviour easier and more automatic. For example, wearing exercise clothes to help get in the mood for exercising, setting aside a quiet spot for work at home, or in the library. [Yeah. I think it’s about removing friction and sort of “nudging” yourself into desirable behaviour.]

- Set yourself up to have minimal distractions – e.g. lock your phone, disconnect from Internet.

- Practise ignoring distractions. Next time you feel the urge to check your phone, pause and acknowledge the feeling. Then ignore it.

- “Eat your frogs first thing in the morning” – i.e. do your most disliked tasks first.

Get enough sleep

Being awake creates toxins in our brain. When we sleep, our cells shrink, increasing the space between our cells. This allows fluid to wash past and push out toxins. [This sounded pretty incredible to me, but it seems to be legit.]

Sleep is a vital part of memory and learning, because it clears out trivial memories and strengthens important connections.

Research also shows that sleep makes a remarkable difference to figuring out difficult problems and understanding what you are learning. [Seems like the diffuse mode point above.] Going over material right before you sleep increases the chance of dreaming about it. (Consciously trying to dream about something also seems to improve your chances further.) And dreaming about what you are learning substantially enhances your ability to understand it.

Other Interesting Points

- Oakley says the brain is designed to do extraordinary mental calculations. We do them when we catch a ball, manoeuvre around a pothole in the road, etc.

- The techniques in the book often seem counterintuitive or even irrational. Oakley spoke to many top teachers who use them, but they divulged them sheepishly, because ordinary instructors often look down on the techniques.

- There’s a negative correlation between creativity and agreeableness. People who are most disagreeable tend to be the most creative.

- The left hemisphere of the brain appears active during the memorisation phase, while the right hemisphere regions are activated in the retrieval phase.

- When we’re stressed, our body puts out chemicals like cortisol, causing us to have sweaty palms, a racing heart, etc. Research shows that if we choose to interpret these as being signals of excitement rather than of stress, it can make a significant improvement in our performance.

- Don’t feel guilty if you can’t get yourself to work too hard the day before a big exam. If you’ve prepared properly, this is natural – you are subconsciously pulling back to conserve your mental energy.

My Thoughts

A Mind for Numbers is primarily aimed at students who struggle with science and math (Oakley herself was such a student). It is therefore a short and very accessible read – Oakley uses memorable metaphors with pinball machines and octopuses to make her points stick. She also refers to evidence to support her claims and responsibly points out where the evidence is relatively weak. There are some short excerpts or “case studies” at the end of each chapter, which people may find interesting or motivating. I’ve only referred to two in my summary above.

However, the book should appeal to many people who aren’t students. It can be used by pretty much anyone who wants to learn more effectively.

There’s two parts to the book – the first is about learning how to learn. The second is about developing good habits and overcoming procrastination. I found the first part a lot more enjoyable and personally relevant – I don’t really have to do well at tests and exams anymore and I don’t have too many problems with procrastination.

Moreover, a lot of tips from the second part I’d already heard, and I’ve already implemented the ones that suit me. Writing summaries actually incorporates many of the recommendations in A Mind for Numbers. I find summaries to be a very effective way to learn – and this was the case even back when I was in school, long before I read this book or took the Learning How to Learn course. One of the great things about producing summaries is that you have something tangible to show for it, and you can also refer back to it later. The same can’t be said for passive re-reading or testing yourself.

Overall, it’s a well-written book and worth a read if you are passionate about learning. Although it’s fairly repetitive, that’s intentional to drive the ideas home. For example, there’s a short summary at the end of each chapter, as well as “test” questions to make you practise active recall. It also uses interleaving and spaced repetition – for example, it introduces the idea of chunking in Chapter 4, takes a break to talk about procrastination in Chapters 5 and 6, then circles back to chunking in Chapter 7. In this way, Oakley seeks to demonstrate the effectiveness of the techniques she recommends.

Buy A Mind for Numbers at: Amazon | Kobo <– These are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase. I’d be grateful if you considered supporting the site in this way! 🙂

Have you read this book? Did you find this summary useful? Let me know by dropping a comment below. If you have a friend or family member who would find this summary useful, share it with them!

If you enjoyed this summary of A Mind for Numbers, you may also like:

One thought on “Book Summary: A Mind for Numbers by Barbara Oakley”

Hey this was genuinely helpful, thanks!