Disclaimer: this post is nitpicky. As the title suggests, it will focus exclusively on the problems with Clear’s book, rather than the upsides. But I don’t actually think it’s a bad book. In my summary of Atomic Habits, I said I thought it was easy to read and clearly written. And while I personally didn’t gain much from it, it seems to be very popular and I’m sure it’s had a positive impact on many lives.

With that out of the way, let me explain my criticisms of Atomic Habits.

Buy Atomic Habits at: Amazon | Kobo (affiliate links)

Exaggerated practical experience

Clear admits that he felt like a bit of an imposter when he first started writing about habits on his blog. He’s not a behavioural scientist or academic—he’s just a very successful blogger who experimented alongside his readers. Clear offers up a synthesis of other people’s findings in fields like biology, neuroscience, and psychology, instead of explaining any novel findings of his own. And that’s all fine.

But he makes some pretty big claims at the start of the book, which don’t really seem to check out. In the first chapter, Clear asserts, “science supports everything I’ve written …”. Okay, then. Let’s hold him to that standard.

Also in that first chapter, he writes:

At the start of 2017, I launched the Habits Academy, which became the premier training platform for organizations and individuals interested in building better habits in life and work. Fortune 500 companies and growing start-ups began to enroll their leaders and train their staff. In total, over ten thousand leaders, managers, coaches, and teachers have graduated from the Habits Academy, and my work with them has taught me an incredible amount about what it takes to make habits work in the real world.

This paragraph gives the impression that he’s worked closely with tens of thousands of people on improving their habits, and that he drew on that experience in writing this book. However, Atomic Habits was published in October 2018, so if Clear started the Habits Academy in 2017, that leaves very little time to learn from it. Moreover, as far as I can tell, the Habits Academy is simply an online course, which Clear doesn’t mention in the above excerpt. It’s not even a live intake online course — the website just promises some pre-recorded video lessons and worksheets. I’m therefore a bit dubious how Clear’s work with the “over ten thousand” Habits Academy graduates taught him “what it takes to make habits work in the real world.”

Dodgy math used to oversell claims

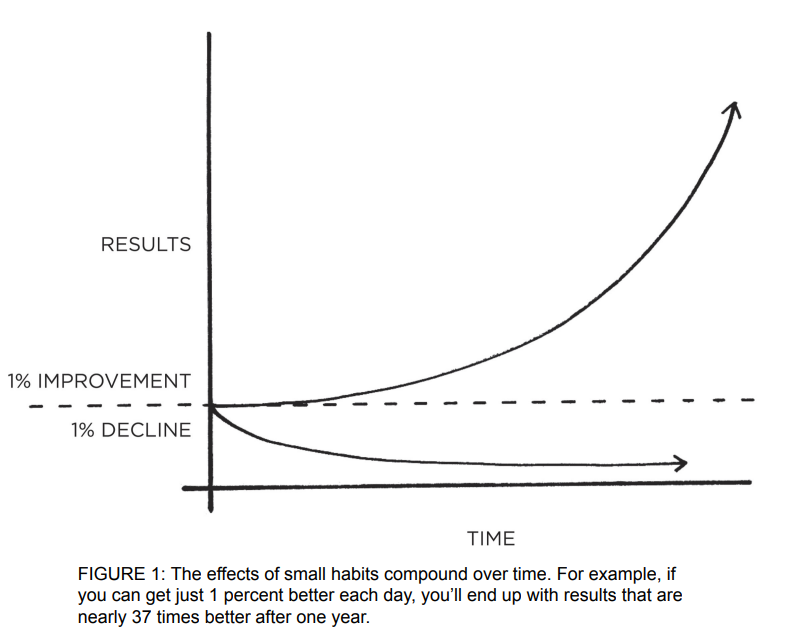

So we’re not off to a great start. Then, in the next chapter, Clear talks at length about how small habits compound.

I seriously doubt small gains always compound. I’m sure some do, and I’ve previously said as much—financial savings certainly do. But some gains may just add up linearly. I expect many gains actually exhibit diminishing returns after a certain point. Exercise could be one example. You’ll likely see much bigger health benefits going from no daily exercise to 1 hour, compared to going from 1 hour to 2 hours.

You may say I’m being pedantic here, but Clear bangs on repeatedly about how “small gains compound” and even draws a bullshit graph to emphasise his point. He is surely overselling the importance of habits.

Later, when sharing his “Never miss twice” rule, Clear again uses dodgy math to bolster his argument:

Lost days hurt you more than successful days help you. If you start with $100, then a 50 percent gain will take you to $150. But you only need a 33 percent loss to take you back to $100. In other words, avoiding a 33 percent loss is just as valuable as achieving a 50 percent gain.

Um… that’s because you’ve used expressed gains and losses as percentages, and that’s simply how percentages work. The absolute value of a given percentage after a gain will always be a bigger number than the absolute value of the same percentage after a loss — e.g. 5% of 90 < 5% of 100 < 5% of 110. This doesn’t prove that “losses are more important than gains”. A $50 loss does not hurt you any more than a $50 gain helps you. Just as he’s used math to trump up the benefits of habits, he’s also used it to exaggerate the downsides of missing a day.

Besides, it’s arguable whether exercising/writing/whatever for a day or two necessarily causes a “loss”. There’s something to be said for making hay while motivation is shining and resting when it is not. On some days, I get completely lost in my work and am incredibly productive. Other days, I might show up, but have little to show for it. Admittedly, it can be helpful to give things a go even when you don’t feel like it, because motivation often kicks in once you get started. But as long as you have enough productive days, and those days are sufficiently productive, you should be able to give yourself a break without really losing ground.

Contradictions

Clear also contradicts himself at various points in the book. When extolling the benefits of environment design, he talks about how motivation and willpower are short-term strategies that can’t sustain behavioural change. But, at other points, he pushes motivation: motivation rituals, habit contracts, and his “never miss twice” rule.

I’m not sure these contradictions are fatal. It’s possible that motivation-based strategies still work, albeit not as well as environment design. Clear just tries to have his cake and eat it too, pushing both types of strategies equally strongly. The problem seems to be that Clear is not an expert on any of this. He’s cobbled together bits of evidence to support different methods, but he doesn’t have any special insight to compare the methods against each other. What you’re left with is a book that throws every plausible method at the wall, some of which will stick.

Overly ambitious in last chapters

Finally, Clear was out of his depth in the last few chapters. He takes on major topics like personality, the role of nature vs nurture, the exploration/exploitation trade-off, flow, and identity. All in fewer than 30 pages.

None of this is handled particularly well. For example, in a section talking about staying focused when you’re bored, he goes off on a largely irrelevant tangent about variable rewards before concluding that, in any case, habits eventually get boring so you just have to suck it up.

I just don’t understand why Clear felt the need to address these areas at all. He’s clearly not an expert, and they’re not even about habits.

Conclusion

None of the above criticisms are fatal to the key points in Atomic Habits. Small gains may not compound, but they still matter. Never missing twice may be an arbitrary rule, but I have no doubt that consistency matters. The 4 steps to forming a habit and corresponding 4 laws of behaviour change appear to be solid. And while the last few chapters were overly ambitious, I doubt they’re actively harmful.

So if you’ve read the book and found it useful, that’s great—don’t let me get in the way. But if you just want to adopt better habits and are tossing up whether to read it, I’d recommend checking out Tiny Habits by BJ Fogg first.

Get Atomic Habits here: Amazon | Kobo or Tiny Habits here: Amazon | Kobo. These are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you buy through these links. I’d be grateful if you considered supporting the site in this way! 🙂

You may also want to check out:

- Book Summary: Tiny Habits by BJ Fogg

- Atomic Habits vs Tiny Habits: Which is Better?

- Book Summary: Deep Work by Cal Newport

Do you agree with my criticisms of Atomic Habits? Or am I being too pedantic? Share your thoughts below!

9 thoughts on “Problems with Atomic Habits by James Clear”

You make some good valid points. But also… perhaps you have become a Tiny Habits fanatic somewhat and now feel it necessary to attack Atomic Habits? I’ve noticed other people take similar stances. Could it also be that you have become a BJ Fogg fan and you like BJ more than you like James Clear? Neither Atomic Habits or Tiny Habits are the best they could be. Neither authors are ideal either. Both books have major faults in the material (contradictions, misstatements, etc.). But both books make mainly good points and are very helpful. So I’m wondering why the need to pick on Atomic Habits? I suspect perhaps it’s because Tiny Habits met your individual needs and now you are a fan. However, other people might find Atomic Habits meets their needs better. It depends on the type of problem a person has with their habits. I bet you could point out big issues with Tiny Habits if you wrote a blog about its problems. I saw you wrote a nice comparison of the two books. I totally agree with your conclusion: “If you do plan to read both, I suggest reading Atomic Habits first to get some general principles and ideas. Tiny Habits will then tell you exactly how to put it all into practice.”. But I would add: “Take the Tiny Habits free 1 week coaching program” because that’s what made me actually put it into practice. And also: “Take the Atomic Habits 30 day free course” but FYI you won’t get free coaching but you get a workbook with checklists and examples. To compare the two books properly, you need to take each approach for a “test drive”. See which helps build habits better for you. Then blog about that with real examples! Thanks for your great summaries and blogs! I appreciate being able to reply here also! Cheers!

Hi! Thanks for commenting and for sharing your experiences with each of Atomic Habits and Tiny Habits’ courses/coaching programs. I do point out in my post above that I don’t think Atomic Habits is a *bad* book and that if you found it useful — great!

While I do certainly prefer Tiny Habits overall, I wouldn’t say I’ve become a “fanatic”. I’m not a fan of the cheesy, twee labels Fogg uses and I also think that Fogg dismisses context prompts. I actually am planning to write a post about my personal experience putting Tiny Habits into practice (which will explain how I don’t 100% follow Fogg’s approach) — but I’m planning to wait a few more months to see if the habits I’ve built so far stick, or grow or multiply, or fall away altogether.

Anyway, thanks for commenting and I appreciate you providing a counterweight to my opinion. Cheer 🙂

Please remember this tip… Tiny Habits is easier if you just “Use the flow charts”. The flow charts in the appendix visually explain the entire Tiny Habits method. Please see the reply I posted on your Tiny Habits book review page for details.

Thanks for the tip. It’s odd – I don’t see a comment from you on my Tiny Habits summary page though. You’re talking about this page, right? https://www.tosummarise.com/2023/01/23/book-summary-tiny-habits-by-bj-fogg/

Yes that page, I posted it twice because it didn’t get acknowledged the first time. I gave-up after the second try. Perhaps Akismet saw it as spam. I will post it a third time but this time I will make it smaller, and I will post the resource link in a separate reply.

Like you, I don’t have a problem with many of the ideas that Clear reports. I’m assuming that this book has helped many people successfully change their habits. My concern is an extension of yours. When lay people write books/blogs/speeches about things that they are not an expert in, but have gleaned from anecdotes, and this is all believed as ‘true’ by many people, it adds to disinformation, and the watering down of critical thinking. This book is not telling people to, for example, avoid vaccines, because they ‘know someone who had a heart attack shortly after getting a vaccine’. But it’s a slippery slope, and people become comfortable believing things they are told without any scientific proof. Anecdotes do not equal data.

Thanks Debra! I actually wrote a post called Anecdotes are not evidence which talks about some of your same concerns 🙂 I believe it’s possible to use anecdotes appropriately in non-fiction, but responsible writers should make their limitations explicit. Clear, unfortunately, didn’t really do that.

Hello, my wife just bought the book and we had a vivid discussion on the matter of 1% from first chapter. For me its math out of crazy mind of a salesman that no one can explain but the one above. Probably the book is a positive factor for some but mentally I won’t be able to enjoy it. My brain cant tolerate lack of consistency and arguments out of thin air.

Haha I’m glad to see I’m not the only one getting hung up on the math! 🙂