Yes, it’s another habits-related book summary—this time, Atomic Habits by James Clear. This post summarises the Habit Loop, the 4 laws of behaviour change, and some practical tips you can use in your own life.

Buy Atomic Habits at: Amazon | Kobo (affiliate links)

Key Takeaways from Atomic Habits

- Habits are important because small changes compound, habits save us mental energy, and much of our lives are habitual.

- Focus on changing your processes and identity, rather than on outcomes:

- Focusing on processes can help with motivation.

- In the long-term, what sustains a change is a change in your identity.

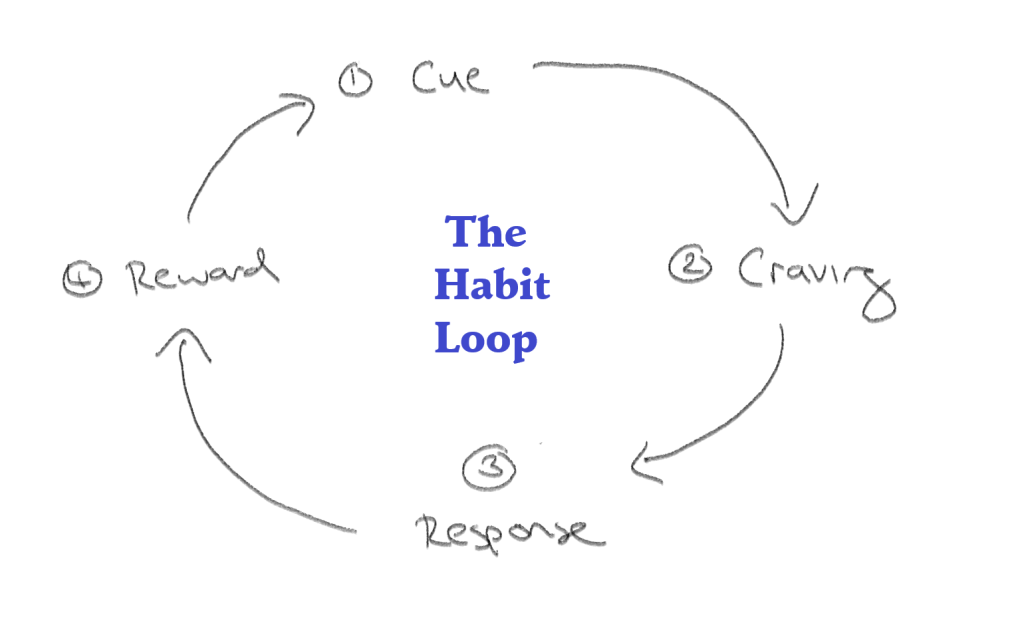

- The Habit Loop consists of the 4 steps needed to build any habit.

- Cue. The cue makes your brain predict a reward.

- Craving. The motivational force that makes you want to act.

- Response. The actual habit or behaviour you do.

- Reward. The reward makes the behaviour occur again in the future.

- From these 4 steps, Clear derives 4 laws of behaviour change:

- 1st law: Make it obvious (good habits) / invisible (bad habits). Specific strategies include: implementation intentions; habit stacking (basically a shortened version of the Tiny Habits method); and environment design.

- 2nd law: Make it attractive (good habits) / unattractive (bad habits). Specific strategies include: temptation bundling; using peer pressure, finding alternative ways to address underlying motives; focusing on benefits of good habits; and motivation rituals.

- 3rd law: Make it easy (good habits) / difficult (bad habits). Specific advice includes: repeat your habit; adjust the friction in your environment; and scale down your habit.

- 4th law: Make it satisfying (good habits) / unsatisfying (bad habits). Specific advice includes: tracking your habit in some visual way; habit contracts and accountability partners.

- In the last few chapters, Clear includes some high-level, general advice about finding things you’re good at, putting in your reps even when you’re bored, and reflecting and reviewing yourself to find ways to constantly improve.

Detailed Summary of Atomic Habits

The importance of habits and persistence

What are habits and why are they important?

The book is called Atomic Habits because, like atoms, habits are tiny. But, also like atoms, habits are building blocks, which form part of a larger system. Habits are the building blocks of “remarkable results”.

Clear gives three reasons why habits are important:

- Small changes compound;

- Habits save mental energy;

- Almost half our lives are habitual.

Small changes compound

If you get 1 percent better each day for one year, you’ll end up 37x better by the time you’re done. Conversely, if you get 1 percent worse each day, you’ll decline to nearly zero after a year.

For example, Great Britain’s professional cycling was relatively crap until the governing body hired Dave Brailsford. Brailsford made a lot of tiny 1% improvements — commonly referred to as the “marginal gains” approach. As a result, British Cycling won a lot of Olympics gold medals as well as the Tour de France. [Interestingly, as Atomic Habits was going to print, Clear found out about doping allegations surrounding British Cycling. He manages to squeeze in a footnote with a link addressing this. He correctly points out that this does not undermine his point about how small gains can add up or compound.]

Habits save mental energy

A habit is a behaviour that has been repeated enough times to become automatic. Habits are useful because they are mental shortcuts. Rather than being dull and constraining, they give us freedom. By making simple tasks automatic, they free up our minds to focus on more important things and to be creative.

When you come across a new problem, your brain is very active in deciding what to do. If the action you end up taking leads to a reward, your brain remembers that. It’ll try that action again next time you face the same or similar problem. As you keep repeating that action, the amount of brain activity each time decreases. It becomes a habit.

Almost half our lives are habits

Researchers estimate about 40–50% of our actions each day are habitual. [This sounded remarkable to me, so I did a quick search. It seems legit.] Clear claims habits are even more important than that number suggests, because they can shape the actions that we take for minutes or hours afterward. Our habits serve as an entry point for our later actions.

Every day, we face a few “decisive moments” where our choices have an outsized impact. For example, the moment you decide between ordering takeout or cooking. Mastering these decisive moments is important because our decisions in these moments limit our future options.

Persistence, patience and process

Persistence and patience

Whether you’re travelling in the right direction is more important than where you currently are, because your outcomes are a lagging measure of your habits. It doesn’t matter if you aren’t yet successful because, if your process and habits are good, you’ll get there.

Although compounding is very powerful in the long run, it doesn’t look very impressive initially. We expect progress to be linear, but it’s not – the biggest pay-offs are delayed. What looks to be an “overnight success” often follows lots of hard work. It’s like melting an ice cube: when you raise the temperature from 25°F to 31°F, nothing seems to happen; when you raise it from 31°F to 32°F, it melts. But the work raising the temperature from 25°F to 31°F is not “wasted”. It’s just stored until it passes a critical threshold. So, while it can feel frustrating to see little progress initially, it’s important to persist past those early stages.

Process and systems

One way to keep motivated is to focus on systems instead of goals. Goals are the results you want to achieve. Systems are the processes that lead to those results. If you have good systems, it should lead you to good results.

The score takes care of itself.

A downside of focusing on goals is that it can have a “yo-yo” effect. Once you’ve achieved a goal, now what? Many people revert back to their old habits after achieving a goal. Focusing on systems is playing the longer game.

Another advantage of focusing on systems is that you don’t have to wait for good outcomes to be happy. You can be happy now, if your system is running well.

Change is about identity

Clear emphasises the importance of changing your identity, instead of merely your outcomes, in achieving lasting behaviour change. Incentives can kick-start habits, but identity is what sustains them.

Our habits shape our identities and our identities shape our habits. It’s a two-way street:

- Habits shape our identities. Every action you take forms a bit of your identity. Each time you write a page, you are a writer. When you change what you do, you who you are. Habits can therefore help you become the type of person you want to be.

- Identities shape our habits. Our behaviours usually reflect our identities, even if not consciously. We feel internal pressure to maintain our self-images and behave consistently with them. Someone who identifies as a “non-smoker” simply doesn’t smoke, whereas someone who’s “a smoker trying to quit” might do so.

It’s okay if you’re not sure what kind of identity you want. Start from the outcomes you want and then work backwards from there. For example, if you want to write a book (an outcome), you might infer that only reliable and consistent people write books (an identity). So you shift your focus from writing a book to becoming a reliable and consistent person.

Take stock with the Habit Scorecard

Before you set out to change your habits, take stock of your existing daily habits. Clear suggests using his Habits Scorecard template [You need to give your e-mail address to download it, but it’s just two columns: on the left, you list all your habits; on the right, you put a +, – or = sign depending on whether the habit is good, bad or neutral.].

It’s easy to forget that our existing habits are habits because we do them so automatically. The point of this exercise is to make the unconscious conscious by calling it out. Clear likens it to the Japanese railway’s “Pointing-and-Calling” safety system, where railway officers call out loud the status of important indicators. Although it sounds silly, the system reduces errors by up to 85% and accidents by up to 30%.

4 steps to building a habit (the Habit Loop)

The 4 steps to building a habit are, in the following order:

- Cue. Your brain receives a bit of information and predicts a reward.

- Craving. Because the cue makes the brain predict a reward, it triggers a craving. Craving is the motivational force behind each habit. Without some motivation or craving, we won’t act at all.

- Response. The response is the actual habit you perform. This is a function of motivation to perform an act and the friction associated with that act.

- Reward. All the earlier steps lead to the reward: the cue makes us notice a possible reward; the craving makes us want the reward; the response obtains the reward. Rewards make the behaviour happen again in the future.

This is the Habit Loop. It’s a neurological feedback loop that creates habits. All 4 steps are needed for a habit to form. The first 3 steps ensure that a behaviour occurs. The final step ensures that it repeats.

Clear sets out 4 laws of behaviour change, which link back to these 4 steps, to help you create good habits or break bad ones.

- Cue: Make it obvious (good habits) / invisible (bad habits).

- Craving: Make it attractive (good habits) / unattractive (bad habits).

- Response: Make it easy (good habits) / difficult (bad habits).

- Reward: Make it satisfying (good habits) / unsatisfying (bad habits).

The first three of these laws affect the chances of a behaviour happening. The fourth law affects the chance that the behaviour will repeat.

1. Cue: Make it obvious (or invisible)

Clear discusses several strategies to create obvious cues:

- Implementation intentions;

- Habit stacking; and

- Environment design.

Implementation intentions

An implementation intention is when you decide in advance when and where you will do something. For example, “When situation X arises, I will perform response Y.” Implementation intentions force us to be specific, instead of relying on vague plans like “I will exercise more”. They also make it easier to say no to any distractions that crop up.

Implementation intentions take advantage of the two most common cues, time and location. When the time and place is right, you don’t need to make a decision, nor do you have to wait for inspiration. You can simply follow your plan.

Implementation intentions study

One study compared three groups of people:

- Group 1 was the control group, who just had to track how often they exercised.

- Group 2 was the motivation group. In addition to tracking their exercise, researchers gave this group information about the benefits of exercise.

- Group 3 was the implementation intention group. They received the same information as Group 2, but they also wrote down a sentence saying exactly when and where they would exercise over the next week.

In the first two groups, 35% (Group 1) and 38% (Group 2) of people exercised at least once per week. In Group 3, this rose to a whopping 91%. [I wonder if the Group 3 people also set a reminder, even if they weren’t told to. The original study says that none of the Group 3 people reported forgetting to exercise, whereas 14% of Group 1 and 19% of Group 2 did. I know I‘d forget unless I set a reminder.]

Habit stacking

Habit stacking is one form of an implementation intention. Clear uses the term “habit stacking” to refer to BJ Fogg’s suggestion to use your existing habits as cues to trigger a new habit. You can do this multiple times, chaining multiple habits together.

Habit stacking implicitly builds in the time and location that you will do your new habit. The frequency of your new habit should match your existing one, and your new habit should occur at a time and place when you’re not busy with something else. The cue should also be very specific.

Clear suggests using habit stacking to create rules to guide your future behaviour. For example:

- When I walk into a party, I will introduce myself to someone new.

- When I want to buy something over $100, I will wait 24 hours first.

- When I fill my dinner plate, I will put veggies on the plate first.

[There’s a lot more on this idea and how to implement it in my summary of Tiny Habits by BJ Fogg. Fogg does not use the term “habit stacking”. Instead, he talks about using action prompts or anchors. Fogg’s approach also differs slightly from the one here — it’s more about fitting new habits into your existing routines, whereas Clear’s is more about deciding in advance how to act in future situations.]

Environment design (particularly for bad habits)

Habits thrive in stable and predictable environments. Over time, habits become associated with an entire environment or context, rather than a single trigger. Even if you break a habit, you probably won’t forget it because its mental pathways are carved into your brain. So one of the best ways to break a habit is to remove its cue, by changing your environment. Don’t rely on self-control — that’s just a short-term strategy.

Soldiers returning from Vietnam

Lee Robins looked at US soldiers who had been heroin users in Vietnam returning home. After they came home, only 5% became relapsed within a year, and 12% within three years. People had thought heroin addiction was almost impossible to kick, yet around 90% of these soldiers got clean practically overnight.

This was because their environment changed. In Vietnam, they were surrounded by cues triggering heroin use all day. Those cues did not exist at all in the US.

You can apply this to your own life. For example, you probably shop on autopilot at your regular supermarket. If you’re trying to eat healthier, try to shop at a new one. If you can’t completely change your environment you could rearrange your current one so that the context of one habit doesn’t mix with another. Use separate spaces for different tasks like work, study, exercise, entertainment and cooking. Don’t relax in the same place you do your work.

You can even do this with digital spaces. Phones and computers today can perform so many tasks, making it hard to associate with just one thing. Try using your computer only for work, your tablet only for fun and your phone only for calls and text.

2. Craving: Make it attractive (or unattractive)

Our brains constantly try to predict what will happen next. These predictions can lead to cravings — the feeling that something is missing and a desire to change it.

The role of dopamine

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that creates desire — or craving — in the brain. It plays a key role in many brain functions, such as motivation, learning and memory. Every addictive behaviour (e.g. drugs, eating junk food, video games, social media) is associated with higher levels of dopamine.

Scientists used to think dopamine was all about pleasure. We now know dopamine is about craving or “wanting” something, as opposed to just “liking” it. When researchers implanted electrodes in rats’ brains blocking the release of dopamine, the rats stopped eating, drinking and having sex. The pleasure centres of their brains still worked, but they didn’t want anything. The rats all died of thirst within a few days.

Our brains release dopamine when we anticipate pleasure. Gambling addicts experience a dopamine spike when they place a bet, not when they win. Dopamine, and our anticipation of a reward, is therefore what motivates us to act.

Ways to induce a craving

Clear suggests several ways to make a desired behaviour more attractive:

- Temptation bundling. This is when you bundle an action you enjoy with a new habit you want to create. For example, only allow yourself to watch your favourite TV show while using a treadmill. The point of temptation bundling is to make your new habit more attractive, by bundling it with an expectation of a reward.

- Use peer pressure. Humans are herd animals with a deep desire to belong. In particular, we tend to imitate people close to us, the many, and the powerful without even thinking. One way to take advantage of this is to join a group where your desired behaviour is the norm. For example, join a book club or a running group. You could take this even further and find a group that you already have something in common with, such as Nerd Fitness.

- Find alternative ways to address your underlying motives. Underlying motives are things like: conserve energy; obtain food and water; find love and reproduce; bond with others; win social approval or prestige; and reduce uncertainty. Every behaviour has a deeper, underlying motive below the surface-level craving. For example you might browse Facebook to connect with others. But there are many ways to address an underlying motive, and there may be better ways to do so. For example, instead of reducing stress by smoking, you might be able to go for a run.

- Focus on the benefits of good habits. Think of the benefits of your new habits instead of their drawbacks to make a habit seem more attractive. Instead of seeing exercise as something challenging and energy-draining, think of it as an opportunity to develop skills and get stronger. Instead of seeing saving money as a sacrifice, think of the freedom that it will bring you in the future.

- Use a motivation ritual. A motivation ritual is when you practise associating your habits with something you enjoy, then using that cue whenever you need a bit of motivation. Athletes often perform a short ritual before each game to get into “game mode”. Once you’ve established that ritual as a habit, your brain associates the cue with a craving, even if the two were originally unrelated. For example, if petting your dog makes you happy, you could create a short ritual that you practise each time before you pet your dog. Over time, you’ll start to feel happy when you do that ritual.

3. Response: Make it easy (or difficult)

Repetition makes things easier

This is one of the most critical steps. Starting a habit feels hard because the mental pathways in your brain have not yet been established. Thinking about each step takes a lot of effort. To get better, you need to practise and repeat it.

Neurons that fire together, wire together.

When you repeat a habit, the physical connections between neurons in your brain activated by that habit will strengthen. Frequency, rather than time, is what matters. The habit becomes more automatic and you may be able to do it with thinking. For example, researchers found that London taxi drivers had a significantly larger hippocampus — the part of the brain that deals with spatial memory — than the general population. When a driver retired, their hippocampus shrunk.

Adjust the friction in your environment

Environment design can make a habit easier (by reducing friction) or harder (by increasing friction). Sometimes this will require a bit of initial effort, but that effort can pay off repeatedly. Technology can help with this.

| Ways to reduce friction | Ways to increase friction |

|---|---|

| To encourage yourself to cook in the morning, get out your cooking implements and utensils the night before and put them on the counter | To make it harder to watch TV, unplug your TV and take the batteries out of the remote after each use. |

| To make exercise easier, get your workout clothes, shoes, gym bag and water bottle ready ahead of time. [I’ve even heard of people sleeping in their gym clothes so they can get up and go in the morning without even changing.] | To stop yourself gambling, ask to be added to the banned list at casinos and online poker sites. |

| To make it easier to eat healthy, chop up fruits and vegetables on weekends and pack them in containers | To stop yourself browsing social media during the week, get someone to change your password and only give it to you on the weekend |

Scale down your habit

Another way to make it easy is to scale your habit down to a smaller, “two-minute” version. Once you’ve started doing something, it’s much easier to keep doing it. Your two-minute habit can serve as a “gateway habit” that makes you do other productive things. Even if you can’t automate the whole habit, you can automate the first part, and inertia (the tendency to keep doing what you’re doing) helps with the rest.

Some people find this a bit forced, as no one really wants to do just a single push-up. In that case, Clear recommends practising the two-minute version and then stopping. Go for a run, and force yourself to stop after two minutes. The point of this is to master the habit of showing up. Once you’ve done that, you can slowly scale your habit up towards your ultimate goal. [Clear doesn’t provide much detail about how you should scale up a habit.]

4. Reward: Make it satisfying (or unsatisfying)

A behaviour that feels satisfying is more likely to be repeated. Our brains remember when something is pleasurable, so we can do it again.

“Positive emotions cultivate habits. Negative emotions destroy them.”

Companies design their products around this principle. Chewing gum only became popular when Wrigley added tasty flavours to it. Similarly, the minty taste of toothpaste feels pleasant, so it’s easier to brush your teeth than to floss. Researchers have found that giving good quality soap — which smelled nice and foamed easily — to people in Pakistan helped them develop the habit of washing their hands.

The immediacy of the feedback is important. Humans evolved in an immediate-return environment such that our brains have learned to prefer quick payoffs. Bad habits are hard to break because they immediately feel good. Good habits are usually the opposite. So we want to counteract this by adding a bit of immediate pleasure to good habits and some immediate pain to bad habits.

After a habit has been established and forms part of your identity, you won’t need extrinsic rewards any more. Your identity, as well as intrinsic rewards like more energy and a better mood, will sustain that habit. In the soap example, the participants in the intervention group had higher hand-washing rates even 5 years after the researchers stopped giving them soap. They had kept up the habit.

Habit Tracking and visual measures of progress

Visual measures of progress can help with motivation, especially for things you want to stop yourself doing. Clear suggests making the avoidance visible. For example, set up a coin jar or savings account for something you really want, like a holiday perhaps, and then put money in it each time you successfully abstain from buying something.

A habit tracker is one way to visually keep track of your progress. It can take different forms: food journals, workout logs, crossing days off a calendar. One guy even used paperclips — every time he made a (work) call, he would move a paperclip from one jar to another, until he had moved 120 paperclips each day.

Habit tracking has multiple benefits. A study of over 1,600 people found that those who kept a daily food log lost twice as much weight as the control group. Tracking a habit helps:

- Make it obvious. Provides a visual cue to do your habit when you look at your tracker.

- Make it attractive. Is motivating because you don’t want to lose your streak. It can even feel addictive.

- Makes it satisfying. It feels satisfying to cross an item off your to-do list. Habit tracking also helps keep your focus on the process, rather than the outcome.

Arguments against Habit Tracking

Some people don’t like the idea of tracking because it means you have to do two habits. While Clear accepts that tracking isn’t for everyone and everything, he recommends at least trying it out temporarily. To make it easier, you can automate it where possible, limit tracking to your most important habits, and record the measurement immediately after each habit.

One risk with measuring your habits is that you might end up measuring the wrong thing. Goodhart’s law states that when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

Measurements can guide you, but the things we can measure may not be the most important things. If one measurement don’t seem to help, try shifting your focus to other indicators of progress. For example, instead of focusing on your weight, maybe focus on your energy levels.

Never miss twice

Clear’s rule is “Never miss twice”. Life happens. One mistake won’t ruin you, but missing twice is the start of a new habit.

We often get into an “all-or-nothing” mindset, thinking that if we can’t do a habit as well as we’d like, it’s not worth bothering at all. But it’s important just to show up, even on your bad days. In fact, it’s most important to show up on the bad days because it’s not about what happens during the workout. It’s about being the type of person who doesn’t miss workouts. Showing up reaffirms your identity.

Habit contracts and Accountability partners

To get rid of bad habits, make things immediately unsatisfying or painful. Again, the pain must be immediate, strong enough, and reliably enforced. One way to do this is to create a “habit contract” to hold yourself accountable. [I’ve usually heard these called “commitment contracts” or “Ulysses contracts” before.] For example, one guy forces himself to wake up before 6 am every day by scheduling a tweet that goes out at 6:10 am asking people to reply to it for $5 via PayPal (limit 5).

The contract stipulates what you will do and your punishment if you break that commitment. You then need to find people to act as your accountability partners to enforce that contract.

Even if you don’t use a habit contract, you can still use an accountability partner. You’re less likely to give up if you know someone is watching.

How to go from good to great

[The final section of Atomic Habits is called “Advanced Tactics: How to Go from Being Merely Good to Being Truly Great”. It’s more about success than about habits per se. I’ve summarised it for completeness, but only briefly.]

Find your strengths and play to them

Our genes predispose us to do well in different areas, and even influence our personality traits. It’s easier to keep up a habit that aligns with your natural abilities.

To find what you’re naturally good at, consider the exploration/exploitation trade-off. Start out exploring and trying a range of possibilities. After an initial period, switch to exploiting the best thing you’ve found, with some occasional exploring. The balance between explore and exploit depends on whether you’re winning or losing, as well as how much time you have. [Sure, but part of the problem is you don’t know if you’re “winning” because you don’t know whether the options you haven’t found yet are better than the ones you have.]

One way to get an edge is by combining skills in different areas to narrow your niche and reduce competition. For example, Scott Adams, combined drawing, comedy and his business background to create the Dilbert cartoons.

Everyone has at least a few areas in which they could be in the top 25% with some effort. In my case, I can draw better than most people, but I’m hardly an artist. And I’m not any funnier than the average standup comedian who never makes it big, but I’m funnier than most people. The magic is that few people can draw well and write jokes. It’s the combination of the two that makes what I do so rare. And when you add in my business background, suddenly I had a topic that few cartoonists could hope to understand without living it.

Stay motivated by doing stuff that is challenging, but not too challenging

Work on tasks that are on the edge of your current abilities — not too easy, not too hard— to stay motivated. This is known as the Yerkes-Dodson law. Researchers estimate that to achieve a state of “flow”, a task must be around 4% beyond your current ability, though obviously it’s hard to be this precise in real life.

Clear recognises this apparent contradiction with his “Make it Easy” rule, and tries to reconcile the two by saying that “Make it Easy” applies when you’re starting a new habit. Once you’ve established a habit, however, you should slowly increase the challenge to keep engaged.

Keep going even when you’re bored

Mastery requires practice. Practice is boring. In the early beginner stages, you might make big improvements, which feels exciting and motivating. But those gains drop off.

At a certain point, the difference between who succeeds may just come down to who can tolerate boredom better. That is often the difference between professionals and amateurs — professionals show up even when they don’t feel motivated. You just have to “fall in love with boredom”.

Keep reflecting and improving

A downside of habits is that you can become less sensitive to feedback as you go about things on “autopilot”. Complacency sets in and you stop thinking about how to improve. To keep improving, you need to combine habits with deliberate practice.

Clear recommends establishing a system for reflection and review once you feel you have mastered a skill, so you’ll be aware of your mistakes and areas for improvement. For example, some people keep “decision journals” where they record their major decisions and expected outcomes. They then review their decisions at the end of each month or year to see what things they got right and wrong.

Clear reviews himself every six months. Each December, he notes down his progress on a range of different measures and reflects on what went well or not. Six months later, he conducts an “Integrity Report”, focusing on areas where he’s made mistakes.

Keep your identity flexible

The more rigid your identity is, the less adaptable you are. Habits can lock us into certain patterns of thinking and acting, even as the world changes around us.

You can make your identity more flexible by redefining yourself based on characteristics rather than particular role. If you define yourself as “a person who is mentally tough and loves physical challenges” instead of as “an athlete”, you can keep your identity even if your role changes.

Further references

Clear sprinkles a lot of links to extra resources throughout the book, which I have listed below. For most of them, you have to enter your email but just once.

- www.atomichabits.com/endnotes – no sign-up needed.

- www.atomichabits.com/cheatsheet – printable summary/cheat-sheet.

- www.atomichabits.com/parenting – Bonus chapter, 8 pages.

- www.atomichabits.com/business – Bonus chapter, 19 pages.

- www.atomichabits.com/habitstacking – really basic, not worth signing up for. Is a shorter version of the Tiny Habits toolkit.

- www.atomichabits.com/tracker – really basic, not worth signing up for.

- www.atomichabits.com/contract – template and example of a Habit Contract.

- www.atomichabits.com/personality – no sign-up needed.

My Thoughts

To be honest, I wasn’t a huge fan of Atomic Habits. It wasn’t necessarily a bad book. It was short, easy to read, and clearly written (no pun intended). Clear also gives a concise summary at the end of each chapter, which I always appreciate.

My main problems were:

- I didn’t learn anything new. This wasn’t just because I had read Tiny Habits earlier that same month (though that probably didn’t help). Rather, I think Clear’s ideas are already in the mainstream, so I felt I’d heard most of it before. Perhaps if I had read the book when it had first been published in 2018, I would have felt differently.

- I probably wasn’t the target audience for the book. Atomic Habits is for people with big dreams. I don’t have big dreams. I just want to sleep a bit better, use my phone less, and get my partner to tidy up after herself. Those things would significantly improve my life. I’m not interested in “getting my reps in” or “falling in love with boredom”, such that I might one day, if I’m lucky, become a star blogger or Olympian (ha!). The book takes on a rather grandiose tone that I found off-putting and, somewhat paradoxically, de-motivating.

- I didn’t really trust the author. This one’s a biggie. It’s hard to enjoy a book after the author loses my trust. Unfortunately, this happened in the very first chapter, and I then found myself reading it with an overly critical eye. I explain how Clear lost my trust in a separate post about the problems with Atomic Habits.

I almost feel bad for not liking Atomic Habits. It’s a very popular book and I’m sure it’s made a real, positive impact in many people’s lives. It just didn’t do anything for me.

If you want to buy Atomic Habits anyway, you can do so at: Amazon | Kobo <– These are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase. I’d be grateful if you considered supporting the site in this way! 🙂

Am I being too harsh on Atomic Habits? Has it improved your life? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

You may also want to check out: