Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity by David Allen is a true classic in productivity circles. This summary explains how you can use Allen’s 5-step system to get control over the dozens of tasks you face in daily life.

Buy Getting Things Done at: Amazon (affiliate link)

You may also want to check out my blog post on Getting Things Done vs Deep Work

Key Takeaways from Getting Things Done

- The aim of Getting Things Done (GTD) is not simply to get more done.

- The point is to become appropriately engaged with your work and life and to eliminate distractions, stress and anxiety. You want have a mind like water, able to respond and focus when you need to.

- Open loops distract us and make it hard to focus. The GTD system gets these loops out of your mind and into a reliable, trusted system.

- GTD involves 5 steps:

- Capture. Put everything into physical or digital in-trays so you have no open loops.

- Clarify. Separate out the actionable from non-actionable items. For all actionable items, decide on what the next action will be. If the next action takes less than 2 minutes, just do it immediately (the 2-minute rule).

- Organise. Put your remaining ‘next actions’ on your calendar or on separate lists so they are available when and where you need them. If a task involves more than one action, treat it as a project and record it on a Projects list.

- Reflect. Do a weekly review of your open loops and make sure your system is complete and up-to-date.

- Engage. As long as you’ve done the previous steps, you can trust your intuition to decide what to focus on at any point.

- GTD is a lifelong practice and you’ll get better at it over time.

- You can expect to get blown off course a few times, but it’s easy to get back on track.

- It can easily take 2 years to get to a stage where GTD feels fully integrated with your life.

- But you don’t have to implement GTD in full to benefit from it. Finding a few “good tricks” may be enough to make reading the book (or this summary) worthwhile.

Detailed Summary of Getting Things Done

The aim of Getting Things Done

We feel anxiety when we feel like we should be doing something that we’re not. We get distracted by open loops — anything pulling at our attention that does not belong where it is, the way it is. For example, replacing the porch lightbulb is an unhelpful open loop if it occurs to you at a meeting where you can’t do anything about it.

To achieve a mind like water, you need to capture all our open loops in some trusted system outside your head:

What you’re doing is exactly what you ought to be doing, given the whole spectrum of your commitments and interests. You’re fully available. You’re “on.”

Step 1: Capture everything

It’s a waste of time and energy to think about things that you need to do without doing them. You want to be adding value when you think about projects, not getting stressed out by reminding yourself of that obligation.

You should even capture tasks that seem unimportant, else they will detract from your ability to focus. Once you can capture and process reliably, your brain can trust the system and stop holding onto them.

Three guidelines:

- Capture everything. If you’re not sure whether something is worth keeping, just capture it anyway and decide on it later. Allen recommends dating everything, too — most of the time it won’t matter, but it’s still worth developing the habit for the few times it really does.

- Minimise the number of capture locations. Too many capture locations make it harder to process consistently.

- Empty your in-trays regularly. This doesn’t mean doing every task in your in-tray. It just means thinking about it and finding a place for it in your system (more on this in the next step).

Your capture tools should be easily accessible so that you can capture wherever you happen to be. Allen suggests using ‘in-trays’, whether physical or digital. You’ll need a workspace at home as well as your office (if you have one). The capturing tools you use won’t, by themselves, give you stress-free productivity. But you still want to set yourself up well enough to implement the GTD system:

A great hammer doesn’t make a great carpenter; but a great carpenter will always want to have a great hammer.

Step 2: Clarify

The reason people often leave things piled up in in-trays is because they lack of effective systems downstream. Their organising systems don’t work because their lists are just full of amorphous ‘stuff’. Actionable items are mixed in with non-actionable items, and no thought has been given to what needs to be done to push their various projects forward.

The vast majority of people have been trying to get organized by rearranging incomplete lists of unclear things; they haven’t yet realized how much and what they need to organize in order to get the real payoff.

This step requires some thinking to transform all that amorphous ‘stuff’ into concrete ‘next actions’. The first question to ask of each item in your in-tray is, “Is it actionable?” This doesn’t require a lot of thinking, but it will make a huge difference. You can only manage your tasks after you’ve clarified what the next action is.

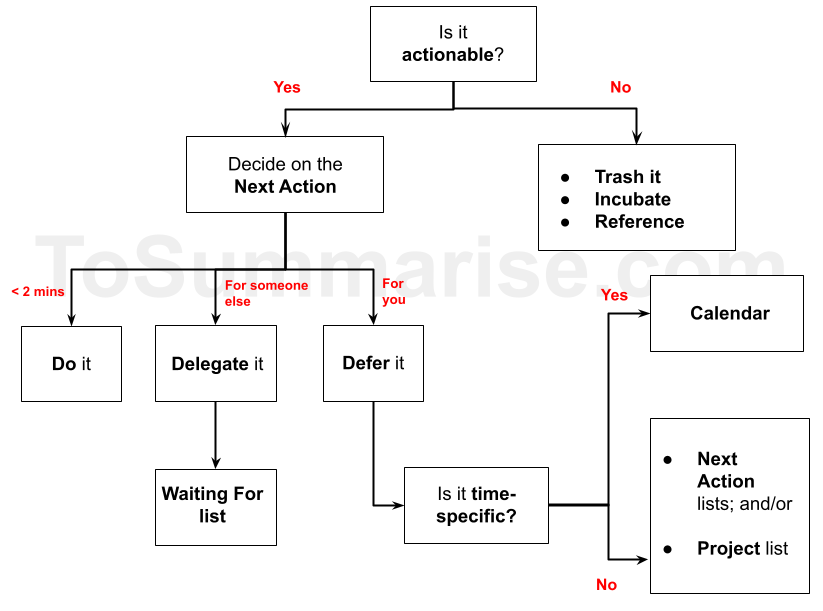

The workflow diagram below sets out steps 2 and 3 of the GTD system:

Non-actionable items

There are 3 options for non-actionable items:

- Trash. If there’s no point in keeping it for reference or later action, trash it.

- Incubate. You may not want to act on it now but you don’t want to completely forget about it either.

- Reference. File it so you can find the material when you’ll need it later.

Don’t use non-actionable items as reminders!

One of the biggest problems Allen sees is when people blend a few actionable items with a large amount of non-actionable information, which clogs up the whole system. But once you’ve sorted out the actionable and non-actionable, your reference system shouldn’t induce any guilt or procrastination—it’s just your library.

Incubate

Allen suggests putting reminders of things you want to incubate into a ‘tickler’ file (which seems very old-school so I won’t get into here), your calendar or a Someday/Maybe list. Which one you choose depends on when and how you want to be reminded of it.

Your Someday/Maybe list can contain optional projects you’re not sure you want to commit to, such as “Learn Spanish” or “Take a cruise”. Over time, you may tick off some of these items without making a conscious effort to prioritise them. Other items may fall off as your interests change.

Long-term vs Someday/Maybe projects

A long-term project is not the same as a Someday/Maybe one. “Long-term” doesn’t mean “no need to decide next actions because the day of reckoning is so far away”.

A long-term project simply has more action steps until it’s done.

You may also want to keep Someday/Maybe lists that you review only when you want to engage in a particular activity — e.g. books to read, recipes to try, movies to rent. These lists may fall into a grey zone between Someday/Maybe and Reference.

Reference

There’ll be many things that don’t require an action but that you still want to keep for reference later. You’ll want to store these somewhere you can easily find later, as required.

Allen recommends keeping a single general-reference system for random bits of interesting or useful things that don’t fit into your more specialised filing systems. Your general-reference files should be easily accessible — it should take less than a minute to file anything and it should be within reach of where you sit. The lack of a good general reference file can be one of the biggest obstacles to implementing an efficient system. If it’s too difficult to file things, you won’t, and then things pile up into big, unprocessed heaps and clutter up your mental space.

Digital storage space is so cheap that it can be tempting to just capture everything without ever using it. While Allen thinks it’s fine to capture things “just in case”, you still need to give some thought to organising it to keep your digital library functional. Relying solely on the search function is, in his experience, suboptimal.

Actionable items

If an item is actionable, work out what the ‘next action’ is. The ‘next action’ is the next physical, visible activity that needs to be done to move your ‘thing’ towards your desired outcome. For example, if you’re planning a party, the next action may be to research possible venues or decide on the date. If you want to exercise more regularly, the next action may be to set up a regular exercise program, or sign up for a gym.

Working out the ‘next action’ takes just a few seconds of focused thinking, and you’ll have to do it at some point anyway. But there are enormous benefits to doing this thinking upfront, before the circumstances force you to. You’ll feel more positive energy, direction and motivation, instead of playing catchup. By contrast, when you don’t clarify the next action, there will be a psychological gap every time you think about your task, which causes resistance, procrastination and guilt.

The secret of getting started is breaking your complex overwhelming tasks into small, manageable tasks, and then starting on the first one.

After you’ve worked out the next action

There are 3 options once you’ve worked out the next action:

- Do it. If the action takes less than 2 minutes, just do the action, even if it doesn’t seem very important (the ‘2-minute rule’). If you haven’t completed the project after doing the next action, you’ll need to work out what the next ‘next action’ is and process that accordingly.

- Delegate it. If you’re not the right person to do the action, delegate it to the appropriate person. Then put it on a “Waiting For” list with the date you handed it over and any agreed-upon delivery date.

- Defer it. Most things will probably fall in this residual category. Step 3 (Organise) below addresses these.

The 2-minute rule is perhaps the most well-known part of GTD, but the exact length of time can vary. You may find that 1, 5 or even 10 minutes works better, depending on how many items you need to process and how much time you have. The point is to strike a balance between eliminating unnecessary tracking (at some point, it’s more work to track a task than to just do it) and making sure you can process your in-trays efficiently.

Step 3: Organise

Put all the tasks you’ve clarified into the appropriate places/categories so you can access them when you need to. Allen suggests 7 primary places:

- Calendar (for time-specific next actions);

- Projects list;

- Next Action lists;

- Waiting For list;

- Someday/Maybe list;

- Project support material;

- Reference material.

I will focus on the first three only.

Calendar

Your calendar is for time-specific or day-specific actions and information. For example, a doctor’s appointment plus directions to get to that appointment. You could also put in reminders to decide whether to attend an event, or whether to make a certain purchase — it’s fine to defer decisions when you process and organise your in-trays, as long as you have a “decide not to decide” system in place.

Otherwise, treat your calendar as ‘sacred territory’ and put only actions that you must do that day. While traditional time-management advice is to keep a daily to-do list or put things you want to do on your calendar, Allen strongly advises doing this because of how frequently things can shift throughout the day. If you don’t complete the to-dos on your calendar, you’ll have to re-enter it on another day, which is demoralising and a waste of time. He suggests putting such items on a “Next Actions” list instead.

Next Actions lists

A list is simply a grouping of items with some similar characteristic. Lists allow you to keep track of the total active things you’ve decided to do.

Your Next Actions lists should contain all the more than 2-minute actions you need to track. If have fewer than 30 of these, you could use a single list. But most people have more like 50-150 next actions, so should use separate lists.

One way to organise your Next Actions lists is by context. This lets you get lots of things done when you’re in a certain mode and reduces the energy costs in switch from one mode to another. Another benefit over a single list is that you won’t have to keep mentally sorting out which tasks you can do in the moment (e.g. no point looking at “buy eggs” when you’re at home).

Examples of context-based lists include:

- Calls to make (along with the relevant phone numbers);

- At computer;

- Errands (for when you’re out and about. You may have sublists for grocery stores or hardware stores);

- Read/review; or

- Discuss with manager/partner/children.

You could also have a time or energy-based lists, such as “Brain Gone” or “Quick wins” so you can do stuff even when you’re not in top form.

Of course, these are just examples. What works for you will depend on your life, and your lists will evolve over time. People who have to read a lot for work may keep separate reading lists depending on how rigorous the type of reading is. For others, this structure would be overkill.

Emails

Allen recommends using these different lists in your email inbox — e.g. you can have an @ACTION folder and a @WAITING FOR folder. When you delegate something via email, cc: or bcc: a copy into your @WAITING FOR folder.

You can use your e-mail inbox as an in-tray as long as you empty it regularly. Just make sure it doesn’t become a dumping ground for amorphous “stuff” that you haven’t clarified and organised.

Projects

You can’t really ‘do’ a project. You can only do actions related to it.

Projects often start as small things and slowly morph into something bigger than expected. Allen defines ‘project’ broadly to mean “any desired result that can be accomplished within a year that requires more than one action step”. This covers many things most people wouldn’t consider projects, such as “Hire a staff member” or “Get a new kitchen table”.

Keep a master “Projects List” that you can review weekly so that you can feel okay about what you’re doing and not doing. It doesn’t matter so much how you organise the list as long as every project is on it (though you can have subcategories within the list — e.g. Personal vs Work).

The Projects List is merely an index. The details and plans supporting your project (the project support materials) should be in separate files, folders, or notebooks. Don’t use these support materials as reminders, else you’ll feel like there’s more stuff than there really is and resist working on the projects — you’ll go numb to the files. Instead, make sure you sort through the project notes, identify any action steps inherent in them, and track those actions appropriately.

Step 4: Reflect

You must engage with your system consistently in order to trust it. Each day, you probably only need a few seconds to review your calendar. You’ll also scan your next action lists frequently for all the things you could do in your current context.

Allen also recommends conducting a higher-level Weekly Review to help sustain your system. Look at all your open loops (your calendar, Next Action, Waiting For and Projects lists) and maybe also your Someday/Maybe list. Make sure everything you’ve captured is processed and up-to-date. The point of this review is to stop your mind from trying to take back the job of remembering and tracking things. The more complete and up-to-date your system is, the more you’ll trust it.

Top-Down vs Bottom-Up approaches

In theory, it makes sense to work out your top-level priorities and then determine how that drives the priorities below it. For example, if you want to create a business for yourself, that higher-level vision will determine what projects and actions you take to achieve your vision.

In practice, however, a top-down approach may create frustration if your systems don’t work at the implementation level. When your day-to-day personal organisational systems are crap, you’ll subconsciously resist taking on any bigger projects or goals.

If your boat is sinking, you really don’t care in which direction it’s pointed!

While both top-down or bottom-up approaches can work, Allen has seen more success with the bottom-up approach. Once you get control over your mundane day-to-day obligations, your mind will invariably turn to focus on the higher-level, big picture, stuff. It’s much easier to change a goal than it is to feel confident you can deliver on that goal.

Step 5: Engage

There’ll always be a long list of actions you aren’t doing at any moment. How are you meant to figure out what to do, and feel good about not doing everything else?

Allen recommends trusting your intuition, as long as you’ve done the previous steps.

[Allen suggests three models for helping with this process: a four-criteria model for choosing actions in the moment, a threefold for identifying daily work, and a six-level model for reviewing your own work. Much of this sounded like common sense. For example, the four criteria model involves weighing up the context, time available, energy available, and priority. These models seemed like overkill to me, so I’ve omitted them from this summary.]

Other benefits of GTD

After implementing the GTD system, you may experience the other following benefits:

- Increased energy and creativity. Properly managing all your open loops will make you feel more inspired to do them. Many people feel fantastic after processing their piles because of how much they work they accomplish using the 2-minute rule.

- Improved relationships. When people notice that you can reliably deliver on your commitments, they begin to trust you in a unique way.

- Increased self-worth. Everything in your in-tray is an agreement you’ve made with yourself, something you said you would deal with. So you feel guilt and anxiety when you look at those unprocessed piles because you’re breaking those agreements with yourself. Being able to reliably get things done can therefore increase your sense of self-worth.

- Increased ability to say “no”. One executive admits he used to agree to many things because he didn’t really know how much he had already committed to do. After he implemented the GTD system, he found it easier to say “no” to new requests.

Not being aware of all you have to do is much like having a credit card for which you don’t know the balance or the limit—it’s a lot easier to be careless with your commitments.

GTD in organisations

The GTD principles are just as applicable to organisations as they are to individuals. Senior people in companies often think productivity problems stem from “too much email” or “too many meetings“. Allen argues that the problem is not with “too many” meetings, but with the lack of rigour and focus.

You’ve probably experienced many meetings where the discussion will end without people knowing what the next action is or who will be accountable for it. Allen suggests forcing this “what’s the next action?” question 20 minutes before a meeting ends to allow enough time to clarify next actions. When you get used to asking this question, you’ll likely find that interacting with those who don’t becomes highly frustrating.

Too many meetings end with a vague feeling among the players that something ought to happen, and the hope that it’s not their personal job to make it so.

Another benefit of GTD is that can reduce complaining and increase results. Complaints often contain an implicit assumption that something could be better than it is. Asking “what’s the next action?” forces the issue. If the problem can be changed, change it. If it can’t, then it’s just part of the landscape that you must factor into plans going forward.

Implementing the GTD system

For most people, full implementation will take about two whole consecutive days: one to fully capture your existing inventory of open loops and another to clarify and decide on all those items. Note that capturing your existing inventory doesn’t mean throwing away things you might want. Allen doesn’t advocate minimalism — if you think you want to keep something, keep it. As long as it’s where it needs to be, it won’t gnaw away at your attention.

If you’re not sure you want to fully implement the GTD system, you don’t have to. Many people get value from finding just a few good tricks in the book — the 2-minute rule is a popular example.

Three levels of maturity

GTD is a lifelong practice — it’s the art of dealing with the stream of life’s work and engagements, and life is constantly evolving.

That said, Allen outlines 3 broad stages of maturity:

- Level 1. This is just using the fundamental ideas like capturing everything, clarifying next actions, keeping up-to-date etc. Even though these ideas are quite simple, it can still take a while to grow used to them and it’s easy to regress in stressful times.

- Level 2. At this stage, you can maintain focus and control not just over the day-to-day, but also week-to-week, month-to-month, or even longer time horizons. You’ll be less focused on the GTD system itself but will still be using it. Your Projects list becomes the driver, rather than the reflection of, your Next Action lists. Your projects themselves reflect more accurately your roles, areas of focus, and interests.

- Level 3. When you reach this stage, you can use your freed-up focus to explore your higher-level goals and values, as well as leverage your external brain to produce novel value.

Staying on track

It’s easy to get blown off course if you haven’t had time to ingrain the practices before you encounter some major disruption. One of the most common ways is not clarifying the next action for tasks, so that lists slowly grow back into big amorphous piles of ‘stuff’. Deciding the next action requires that extra bit of effort which is tempting to skip when the particular situation is not yet in a critical mode.

The good news is that it’s easy to get back on track by revisiting the basics — just take some time to empty your head again and clean up your lists and projects. Almost everyone cycles between on- and off-track when they first start. Allen’s experience is it can easily take 2 years to get to the point where you’re fully comfortable with GTD and consistently using it. A significant transition point is when issues and opportunities galvanise GTD practices, instead of causing you to abandon them.

Supporting research

Allen’s recommendations are based primarily on his experiences coaching others. However, in the 2015 version I read, he refers to various research since the 2001 edition came out, which support his advice:

- Heylighen and Vidal (2008) finds support for the GTD method specifically.

- Daniel Levitin’s The Organized Mind supports the idea of using an “external brain”, because of our limited capacity to manage information.

- Baumeister and Masicampo (2011a)) explain how incomplete tasks interfere with mental tasks requiring focus. [Interestingly, this finding is not universal. One of the studies found that people who said they could readily shift amongst their various pursuits didn’t experience task interference.]

- A separate paper by Baumeister and Masicampo (2011b) found that people don’t have to actually complete the tasks to eliminate the negative cognitive effects — making a trusted plan can suffice.

- Along similar lines, Gollwitzer and Oettingen (2011) have described how implementation intentions increase the chance people will realise their goals. (Atomic Habits also discusses implementation intentions.)

Other Interesting Points

- You can find support material and other resources at gettingthingsdone.com (there’s even a GTD podcast!)

- You want both horizontal and vertical control over all your tasks.

- Horizontal control involves having control over all the activities you need to consider at any time. It’s the 5-step process above, especially the weekly review.

- Vertical control involves having control over a particular project (i.e. “project planning”). You’ll want to engage in this occasionally to get bigger projects under control and off your mind. Allen outlines a natural planning model to help with this.

My Review of Getting Things Done

Getting Things Done had some great advice, but the 2015 edition I read was rather repetitive. The first part spent a lot of time explaining how GTD would change my life — I’ve already got the book, please just get to the point!

The second part then provides considerable detail on how to implement GTD. For example, Allen tells you the exact things you need to set up your workspace (e.g. paper clips, Scotch tape, and an automatic labeller), which was more detail than I personally cared for. To be fair, Allen explains that his book is not designed to be read as an ordinary book, but as a manual you can consult at different points of implementing GTD.

With that minor griping aside, I think the advice in Getting Things Done is gold. If it were the first productivity book I’d ever read, it probably would’ve blown my mind. As it is, many of its principles have already worked my their way into my existing systems via other productivity books and videos influenced by GTD.

However, I still found the book worth reading. In particular, the book helped me appreciate the importance of:

- Capturing everything. Before, I didn’t bother to capture stuff I didn’t consider important. But I think Allen’s correct that ‘unimportant’ tasks can still be distracting, so I’ve since stepped up my capturing game.

- Clarifying the next action. I was amazed at how this simple step helped move along many to-dos that had languished on my list for ages.

- Context-specific lists. I’ve experimented with different ways to organise my to-do lists for some time now. I liked Allen’s idea to organise “next action lists” by context, since it reduces context switching and lets you decide what to do based on your energy available at any time.

Allen recommends reviewing Getting Things Done again in 3 to 6 months as you’ll likely notice things you missed the first time through. I don’t plan to do this, but I set up a reminder to read this summary in 6 months’ time. I invite you to do the same 😉

Share your thoughts on my summary of Getting Things Done in the comments below!

Buy Getting Things Done at: Amazon <– This is an affiliate link, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through it. Thanks for supporting the site! 🙂

If you enjoyed this summary of Getting Things Done, you may also like:

4 thoughts on “Book Summary: Getting Things Done by David Allen”

Thanks. I finished the book about 1 week before you posted this :).

I really liked:

– the capture, clarify and organise graphic he included (and that you adapted in your summary).

– the two minute rule

– like you, the emphasis on describing in a concrete way what the next step is

The idea of a “waiting for” list seemed sensible at the time, but when I sat down to create it I actually didn’t really see the value. Maybe it truly clears your mind or something. Just seemed quite a bit of admin.

I understand his point on the sacredness of the calendar, and why that means he doesn’t think you should time block. But the alternative is that your calendar gets filled up with other people’s requests – it gives total supremacy to meetings instead of other work. So I think time blockign is great.

I agree that his various frameworks for subparts of his process were overkill. As was some of the incredible detail about all the types of lists you might have…

Did you notice the intriguing footnote in chapter 9? Chapter 9 has this passage:

“That doesn’t mean you throw your life to the winds – unless of course, it does. I actually went down that route myself with a vengeance at one point in my life, and I can attest that the lessons were valuable, if not necessarily necessary*

Footnote is:

\* There are myriad ways to give it all up. You can ignore the physical world and its realities and trust in the universe. I did that at one point, in my own particular way, and it was a powerful experience. And one I wouldn’t wish on anyone. I tried to check out of my practical connections, though I didn’t choose to end my life (but it was a close call!) I had much to learn about cooperating with the world I’d chosen to play in. But surrendering to your inner awareness, and its intelligence and advice for the worlds you live in, is the higher ground. Trusting yourself and the source of your intelligence is the most elegant version of experiencing freedom and manifesting personal productivity.”

My “Waiting For” list is just a subsection of a bigger “Active” list on my Todoist, so it’s not much admin to move things to and from it. My “Active” list is just a general list with only 20 or so tasks on it, because I’ve organised everything else onto either:

– Calendar/Reminder lists – for time/day-specific tasks.

– Backburner – my Someday/Maybe list (I move things from here to “Active” when “Active” gets low)

– Things to write, read, watch, cook, places to try, etc, which don’t really involve a “Waiting For” component.

No, I didn’t notice that footnote – I don’t think I was reading that closely by the time I got to Ch 9! It is certainly intriguing…. For a guy so focused on personal productivity and organising mundane, day-to-day stuff, Allen writes a lot like a spiritual hippie at times (e.g. your footnote and the “mind like water” thing).

Nice solid review. When I first found this site I had hoped this was a book you had summarised already (the book has so much content and a good summary of it is useful) and am glad that it was on your list.

I agree that the advice on this book is gold – and despite it going in to maybe too much detail in some parts, I like how it offers a full system for capturing all things that need to be done. Integrating “life” and “work” task management systems into one unified system was a game changer for me.

The other key technique that I found very useful was the “natural planning model” for planning out projects. I’ve adopted this as a go-to model for any small project and have found it to be a very useful in framing what I want to get out of the project and figuring out what to do next. Many an item on my to-do list have either been purged or have a way forward thanks to this technique. Somehow, “how to plan” is not something that I ever got in formal education and it seems that everyone kind of expects that you know what to do.

Thanks! I’m glad to hear you found the natural planning model useful. I tossed up whether to include that into my summary but decided against doing so, because it might detract from the main principles. I did like how simple his model was, though.