You’re probably familiar with bad strategy. It’s full of fluff, lofty visions and desirable outcomes, with no clue on how to achieve these things. In Good Strategy, Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters, Richard Rumelt explains how good strategy is different.

Buy Good Strategy, Bad Strategy at: Amazon (affiliate link)

Key Takeaways from Good Strategy, Bad Strategy

- The word “strategy” has been so misused that many people don’t even know what it means.

- Bad strategy fails to face up to the challenge and avoids making hard choices. Bad strategy also fails to bridge the implementation gap — people often confuse strategy with goal-setting and vision.

- The ‘kernel’ of a good strategy has 3 components:

- Diagnosis. Since a strategy must confront the challenge, the first step is figuring out what the challenge even is.

- Guiding policy. This is the overall approach to deal with the diagnosed problem.

- Coherent actions. The kernel doesn’t have to contain every action step, but it has to contain some action to help bridge the implementation gap and those actions should be coordinated to work together.

- Strategy is ultimately about harnessing power and applying it. Sources of power include:

- Advantages. No one has an advantage at everything, as advantage is rooted in asymmetries.

- Understanding systems. One reason why strategy is hard is because the connections between actions and results are not always clear.

- Things to watch out for:

- Attempts to engineer growth. Growth is the outcome of good strategy, not an end to be pursued in itself.

- Inertia. As organisations grow bigger and more complex, they tend to become resistant to change.

- Entropy. Over time, organisations naturally become less organised and focused unless they are properly managed.

- Think like a strategist:

- Strategy is hard and requires analysing unstructured information.

- New strategies are like hypotheses — success is never guaranteed, but you can test and learn from them.

- Be aware of your own cognitive limits and biases. The kernel can help with this as it forces you to think carefully about strategy.

Detailed Summary of Good Strategy, Bad Strategy

What is strategy?

For many people, “strategy” has become a meaningless buzzword. But when a word can mean anything, it stops being useful. The word “strategy” comes from military affairs. Rumelt defines it to mean “a way through a difficulty, an approach to overcoming an obstacle, a response to a challenge”.

While business competition is quite different from military battles, there are still valuable business lessons to be learned from military history. Throughout the book, Rumelt uses a variety of business case studies and military examples to illustrate his points.

What is bad strategy?

Bad strategy is not the same as no strategy or a failed miscalculation. Rather, it is the active avoidance of the hard work of crafting a good strategy.

Bad strategy is a way of thinking and writing about strategy that:

- fails to identify or face up to the challenge; and

- fails to bridge the implementation gap.

It often uses fluff — buzzwords, restatement of the obvious — to hide its shortcomings. People with true insight can make a complex subject understandable. People who lack such insight make things complex to mask the absence of substance. Good strategy almost always looks simple and obvious.

Bad strategy fails to face the challenge

Bad strategy glosses over challenges because of concerns that negative thoughts will “get in the way”. But a strategy that fails to identify obstacles isn’t a strategy at all.

Strategy involves focus and focus requires choice. To try and placate everyone, bad strategy spreads rather than concentrates resources. The result is a long list of desirable outcomes or “things to do”. This is particularly common when decisions are made by consensus—universal buy-in indicates that no real choices have been made.

This failure to define the challenge or to make hard choices and trade-offs is bad strategy. It’s a luxury that rich and powerful organisations can get away with, and it’s common in complex organisations with many stakeholders who have conflicting goals.

Rather than focus on a few important items, the group sweeps the whole day’s collection into the “strategic plan.” Then, in recognition that it is a dog’s dinner, the label “long-term” is added so that none of them need be done today.

Good strategy is as much about what an organisation doesn’t do as it is about what it does. Good strategy focuses energy and resources. Usually, this redirection of resources will make some people worse off, so good strategy often faces resistance.

Example: Intel moves from DRAM to microprocessors

By 1984 it was clear that Intel could not match its Japanese rivals in producing DRAM (dynamic random access memory). Intel CEO Andy Grove made the hard choice of exiting the memory business and refocused the company on making microprocessors instead.

This was not an easy change. The memory business had driven a lot of research, production, careers, and pride at Intel, and it took over a year to make the change. But it was the right choice. By 1992, Intel became the world’s largest semiconductor company.

Bad strategy fails to bridge the implementation gap

Strategy is not the same as vision, planning or goal-setting. Some examples of bad strategy include:

- To be the graphics arts services firm of choice;

- Grow revenue by at least 20% each year;

- Foster an honest and open work environment; or

- To be a learning community that seeks to serve society by educating the leaders of tomorrow and extending the frontiers of knowledge.

These are all statements of mere goals or visions. None of them is an actual strategy that specifies how the organisation will achieve its goals.

Strategy should transform vague goals (the organisation’s overall values and desires) into a coherent set of actionable objectives (specific operational targets). A proximate objective — i.e. on that is close enough to be feasible — can galvanise people and help focus efforts. The more uncertain and dynamic a situation, the more proximate your objective should be because it’s harder to see ahead.

Example: Placing a man on the moon

In 1961, President Kennedy gave a speech calling for the US to put a man on the moon and return him safely to earth by the end of the decade.

This objective was carefully chosen. The Soviet Union had larger launch vehicles at the time, so could be expected to beat the US in any near-term space achievements. But landing a man on the moon would require much larger rockets than either country had. This gave the US an advantage, because it had a larger underlying base of resources.

While the objective may have appeared audacious to laypeople, it was actually quite feasible because US engineers had already developed much of the technology to design and build spacecraft as part of the ballistic missile program.

Every organisation faces situations with overwhelming amounts of complexity and ambiguity. Leaders have the duty to absorb much of that complexity and ambiguity and pass on a simpler, solvable problem. Lower-level units can then look to the high-level proximate objective to work out what their subgoals should be and, in this way, the problem-solving can cascade down the organisation. Many leaders fail badly at this duty.

Inspirational leadership is not strategy

In the mid-1980s, people began to believe that CEOs and other leaders had to be charismatic. The idea was that leaders just inspired and motivated others, and then empowered them to carry out their vision. This idea gained traction because it satisfied leaders’ sense that organisations should “somehow be forced to change” but relieved them from the awkwardness of telling other people what to do.

Charismatic and inspirational vision can indeed motivate people, but inspiration is not a substitute for strategy. Business competition is not just a battle of motivation and grit; it’s also a battle of insights and competencies. While a leader may reasonably call for a ‘push’ to get stuff done, to do their job, they must come up with a strategy worthy of that push.

Planning is not strategy

Many wrongly use the word “strategy” to describe any decision made by the leaders of an organisation, even though many of those are actually planning decisions. Opportunities, challenges, and changes don’t come along in nice annual packages. True strategy work is episodic.

Approving annual budgets or projections for revenues, costs, profits, etc and determining where to allocate resources just maintains the status quo. There’s nothing wrong with planning—it’s just not strategy.

The ‘kernel’ of good strategy

Rumelt sets out the three elements that make up the “kernel” or barebones centre of a strategy:

- Diagnosis to define the challenge — why you are doing this.

- Guiding policy for dealing with the challenge — what you are doing.

- A set of coherent actions to carry out the guiding policy — how you will achieve it.

For example, a doctor’s diagnosis names a disease or pathology. They then choose a particular therapeutic approach as their guiding policy. Lastly, they prescribe medications or lifestyle changes as a set of coherent actions to implement that guiding policy.

1. Diagnosis

Since a good strategy is about finding a way to overcome a challenge, the first step involves figuring out what is even going on. Only after you have a diagnosis can you begin problem-solving.

A good diagnosis simplifies the often overwhelming complexity of reality by identifying certain aspects of the situation as critical.

For example, in 2008, Starbucks experienced flat or declining growth and profits. Were the markets saturated? Were consumer tastes changing? Or had competition intensified? Each of these possible diagnoses is a judgment about the critical issues. None of them can be proven to be correct — each is just an educated guess.

A good strategy that insightfully reframes a situation can itself be a source of power. A good strategic diagnosis should also define a domain of action. Sometimes a diagnosis may classify the situation as being a certain type, which lets you draw on knowledge about similar past situations.

Example: Operation Desert Storm

Towards the end of the first Gulf War, Iraq invaded Kuwait. The US and its coalition members rapidly built up their ground troops but Iraq had a big lead.

US General Norman Schwarzkopf developed a strategy for the ground war involving a two-pronged attack:

- first, air attacks reduced the Iraqi forces by 50%.

- second, while the media focused on the troops in the south, they secretly shifted 250,000 soldiers to the west and north of Kuwait, forming a secret ‘left hook’. When the ground war began, this force slammed into the Iraqis’ flank.

This combined-arms left-hook strategy was very successful. The ground war only lasted 100 hours and the US coalition suffered minor casualties.

The left-hook strategy was hardly groundbreaking. In fact, the US Army publishes field manuals describing its methods and FM100-5 Operations, which was publicly available at the time, even includes a diagram of the left-hook strategy on p 101. Schwarzkopf had simply used one of the US Army’s most basic offensive manoeuvres.

The real surprise wasn’t the strategy itself—it was the fact that a pure and focused strategy was implemented at all.

2. Guiding policy

The guiding policy is the overall approach chosen to deal with the obstacles identified in the diagnosis. Think of the guiding policy like guardrails — it directs some actions and rules out other possible actions, without fully defining the exact steps to be done.

Example: Stephanie’s grocery store

Rumelt’s friend, Stephanie, owned a corner grocery store and wanted to increase profits. Even in a corner grocery store, there are hundreds of possible changes to make.

The first step was to simplify this complexity with a good diagnosis: Stephanie’s challenge was competition with the local supermarket, which had lower prices and was open 24/7.

Stephanie then divided her customers into several categories (e.g. price-sensitive students or time-sensitive professionals). Framing the problem this way drastically reduced the complexity and helped her see a coherent guiding policy: target the busy professional who doesn’t have time to cook.

That guiding policy suggested a set of actions: Stephanie set up a second checkout stand to handle the burst of traffic at 5pm and repurposed some shelf space to sell high-quality prepared meals to professionals.

Stephanie could not be certain that her policy was the best one. But the guiding policy focused and coordinated her efforts. Without it, her actions would have probably been inconsistent and incoherent.

3. Coherent actions

The kernel of a strategy must contain action in order to bridge the implementation gap. It doesn’t need to contain every action step, because these will change as events unfold. But it has to do more than set the big-picture direction.

When executives complain about execution problems, it’s usually because they’ve confused their job of setting strategy with setting goals. Bringing strategy down to the implementation level can help flush out the conflicts that will result when action has to be taken.

The actions in a strategy should also be coherent — i.e. they should work together to overcome the identified challenge. Coordination alone can be one of the most basic and enduring sources of advantage because a well-coordinated strategy is hard to copy.

Example: IKEA’s highly coordinated system

IKEA’s giant retail stores in suburbs allow for large selections and plenty of customer parking. The catalogues in the stores substitute for a sales force. And not only do the flat-pack designs reduce shipping and storage costs, they also allow customers to take their purchases home right away.

IKEA’s strategy is hardly secret. But more than 50 years on, no one has really replicated it. This is because IKEA has many unusual policies that fit together in a coherent system. Adopting only one of these policies won’t work.

Strategy is an exercise in centralised power

The essence of strategy is coordinated action imposed on a system. It’s an exercise in centralised power to overcome the natural workings of a system. Decentralised decisions work pretty well in many cases but can fail when externalities, principal-agent problems and/or short-term thinking is involved.

Example: Walmart’s centralised model

Before Walmart entered the market, the conventional wisdom was that general discount stores could only survive in places with a local population of at least 100,000. This was because you needed enough customers to spread your store’s overhead costs in order to keep retail prices low.

But Walmart succeeded by putting big stores into small towns. Their innovation was to use a network of stores, instead of a single store, as the basic management unit. The population limit of 100,000 still applied — but to the entire regional network.

The previous model used by K-mart (the market leader at the time) was decentralised. Each store manager picked their product lines, vendors and set their own prices. Decentralisation has some benefits, but it also comes with costs — in this case, lost coordination across stores. Decentralised stores had less bargaining power in negotiating good terms with their vendors, less efficient logistics, and couldn’t benefit from each other’s data on what worked or didn’t. Walmart, by contrast, used a centralised distribution system to get gains from coordination.

Kmart filed for bankruptcy in 2002. It was too difficult to copy Walmart’s strategy because its whole design — its strategy, policies and actions — was coherent. Everything complemented each other.

This isn’t to say that centralised coordination is always good. In many cases, the decentralised actor in an organisation will have more expertise and local knowledge than upper management. So we should only seek coordinated policies when the gains from it are very large.

Sources of power

At its core, strategy harnesses power and focuses it at the points where it will have the greatest effect. The most basic idea of strategy is applying strength against weakness — or to the most promising opportunity.

Rumelt lists many things under the “Sources of Power” part of the book: Leverage, Proximate objectives, Chain-link systems, Design, Focus, Growth, Advantage, Dynamics, Inertia and Entropy. Some of these (e.g. Growth, Inertia and Entropy) are not sources of power while others (e.g. Leverage, Focus and Advantage) seem to overlap with each other.

In this summary, I have rearranged these into two broad categories:

- Advantage

- Understanding systems

Advantage

Advantage is rooted in asymmetries. In classic military strategy, higher ground provides a natural advantage as it is harder to attack and easier to defend.

No one has an advantage at everything. In any rivalry, there will be countless asymmetries between the two parties. A leader has to work out which asymmetries can be turned into advantages. They should then press where they have an advantage—and sidestep situations where they do not.

Example: The US vs the Taliban

The US military is much stronger and well-resourced than the Taliban, but there were some key asymmetries that gave the Taliban advantages in the war in Afghanistan:

Perhaps most importantly, the Taliban had time on its side. It cost the US $1 million per year per soldier in Afghanistan. The Taliban could simply wait it out.

Afghanistan has a weak central government and highly localised power and loyalty. Even after years of US support, the Afghan central government has little power outside of Kabul.

The Taliban is not an army and has no uniform. Many people in Afghanistan are connected to someone in the Taliban, but it was hard for the US to tell who.

Focus and leverage

If you can focus minds, energy and action onto a pivotal objective at the right moment, you can leverage your efforts.

There are three elements:

- Anticipating others’ actions. In business, you may anticipate buyer demand and competitors’ reactions. In foreign policy, you may need to anticipate other countries’ actions.

- Finding the right pivot points. Pivot points are asymmetries that magnify the effects of effort.

- Concentrating efforts. Concentrating on the right things can yield large payoffs because of constraints (resources are always limited) and threshold effects (sometimes there’s a critical level of effort needed to affect the system, and efforts below that threshold have little payoff). An example of a threshold effect in politics is the “salience effect” — an intervention that completely turns around two schools can impact public opinion more than one that improves 100 schools by 2%.

Example: Anticipation in the Battle of Cannae

The Battle of Cannae took place in 216 BC on an open field. Carthage, led by Hannibal, had about 55,000 troops while the Romans had at least 85,000. Each army’s front was about a mile long.

Hannibal arranged his troops in a broad arc, bulging out in the middle. At that bulge, he placed troops from Spain and Gaul who had been liberated from Roman rule or hired. This was the first point of contact when the two armies met. The Spaniards and Gauls fell back, which heartened the Romans, who kept moving forward.

But as the Romans pushed in, the arc reversed. At Hannibal’s signal, reinforcements bolstered the centre, which stopped retreating. His heavy infantry flanks moved to surround the Roman army on three sides. Lastly, the cavalry came around and closed off the Roman’s rear. By fully surrounding the Romans, Hannibal completely nullified their numerical advantage.

At least 50,000 Roman soldiers died that day, more than in any single day of battle before or since. [Wow!] About 1/10th of that number died on Hannibal’s side. Rome’s defeat was so great that most southern city-states in Italy declared allegiance to Hannibal.

One aspect of strategy that the Battle of Cannae highlights is the importance of anticipation. Carthage had fought Rome before and understood its military system. In 216 BC, its formula for success was simply: keep in formation, keep discipline, and keep troops from panicking. Hannibal anticipated that if a Roman saw an enemy retreat, they’d think they were winning. He therefore used this to entice them into a trap.

Example: Apple’s focus

When Microsoft released its Windows 95 operating system, it quickly gained market share. Apple, meanwhile, fell into a death spiral. By 1997, it was two months from bankruptcy. Steve Jobs, who had originally co-founded Apple in 1976, returned as interim CEO and implemented a focused and coordinated strategy.

Job cut Apple back to a small core, so that it could survive as a niche producer. Its product line shrunk:

- desktop models went from 15 down to 1;

- portable and handheld models were similarly cut down to one laptop; and

- printers and other peripherals were cut entirely. Jobs made cuts in other areas, too — development, distribution, and virtually all manufacturing. Within a year, Apple’s fortunes radically changed.

The power of Jobs’ strategy came from directly tackling the fundamental problem with a focused and coordinated set of actions. He did not announce ambitious revenue or profit goals; he did not indulge in messianic visions of the future. And he did not just cut in a blind axe-wielding frenzy—he redesigned the whole business logic around a simplified product line sold through a limited set of outlets.

Using advantages to increase value

A business has a competitive advantage if it can produce at a lower cost or deliver more value than its competitors. But the connection between competitive advantage and wealth is a dynamic one — wealth increases when the size or value of a competitive advantage increases.

Example: eBay is like a silver machine

Imagine a passing UFO leaving behind a machine that can produce $10m per year in raw silver at no cost. However, there’s no way for the machine’s owner to make the machine more efficient or to learn from or replicate it. Although the silver machine is very valuable and generates an advantage, its value will be static because its advantage is static.

eBay is like the silver machine. It definitely has a competitive advantage — it can generate value by providing a service at a cost below what its customers are willing to pay. And it has been able to do this well enough that competitors have not been able to steal its core business.

eBay’s advantage, and therefore value, has also been static. Unlike the silver machine, however, there are ways in which eBay could be made more efficient or valuable.

Rumelt suggests 4 different ways to increase the value of something:

- Create or deepen an advantage. This means widening the gap between what a buyer values a product at and the cost of producing it (the surplus). You can do this by increasing the value to buyers, reducing costs, or both.

- Extend an existing advantage. Use your strengths and resources in new ways. Applying knowledge in new ways is often good because it doesn’t get “used up” and may even be enhanced. But using your relationships or reputation in new ways can be riskier — if you fail in the new arena, the damage can rebound to your core.

- Increase demand for advantaged products or services. Creating higher demand will only work if you already have scarce resources that make your competitive advantage stable.

- Strengthen your isolating mechanisms. Isolating mechanisms stop competitors from undermining your competitive advantage. Intellectual property rights like patents or copyright are obvious isolating mechanisms. Relationships, network effects, or tacit knowledge and skill can also work as isolating mechanisms. One way to strengthen isolating mechanisms is to just keep innovating and improving since it’s harder for competitors to copy a moving target.

Understanding systems

One source of power comes from understanding complex systems. Much strategy work involves recognising interactions and trade-offs you face. Changing one part in isolation can create problems for other parts. You want to fit various pieces together so they work as a coherent whole.

A master strategist is a designer. Rumelt uses the word “design” rather than choice or plan to emphasise the adjustment that goes on. One reason why strategy is tricky is that the connections between actions and results are not always direct or clear. For example, we tend to associate current profits with recent actions, even though they’re likely the result of past decisions. This disconnect makes it hard to find the sources of success.

Partial substitutes

Factors of production can sometimes act as partial substitutes for each other. For example, resources and coordination can be partial substitutes. If an organisation has limited resources, it will depend more on clever coordination to overcome its challenges.

But not all factors of production can substitute for each other. Quantity does not always substitute for quality—if a 3-star chef is ill, you can’t just replace them with several short order cooks.

Chain-link systems

Chain-link systems are bottlenecked by their weakest link. You can’t make the chain stronger by strengthening the other links, or adding more links. Incremental changes may not pay off and can even make things worse.

Chain-linked systems are part of the reason why economic development is so hard. If each link in a chain-linked system is separately managed, the whole system may get ‘stuck’. Turning around a chain-link system requires strong centralised direction and coordination, at least for a while.

Example: Tinelli’s machine company

Marco Tinelli had a machine company in Lombardy stuck in a low-profit state because of some chain-link issues:

- Better quality machines wouldn’t help until the sales force could accurately represent their benefits;

- A better sales force wouldn’t help until the machines got better; and

- Better machines and sales would not save the firm unless costs were reduced.

To remedy these three issues, Tinelli conducted three consecutive campaigns focusing first on machine quality, then sales, and lastly cost-cutting.

Even though the first campaign yielded no immediate returns, Tinelli still congratulated his team for achieving their proximate objective of improving machine quality. He took personal responsibility for the short-term losses and kept going because he understood the chain-link nature of the system. In the end, his efforts paid off and his company is now a profitable firm.

Exploiting large waves of change

Sometimes large waves of change come along and disrupt an entire industry. Existing market advantages get erased while new ones get built up.

To exploit such waves, you have to understand how things are likely to play out. This is hard — you have to look beyond the main effects and anticipate the second-order effects. For example, the rise of the microprocessor created at least two different second-order effects: first was a move from hardware to software; second was the vertically-integrated computer industry becoming horizontal. Leaders also need to get into the details, acquire enough expertise to question the experts, and discover the fundamental forces at play.

It is hard to show your skill as a sailor when there is no wind. Similarly, it is in moments of industry transition that skills at strategy are most valuable.

Example: Steve Jobs waiting for ‘the next big thing’

Even after Jobs turned Apple’s fortunes around, it remained a niche producer. In 1998, Rumelt had a chat with Jobs and asked what Apple’s longer-term strategy was. At that time, Apple had less than 4% of the personal computer market. Rumelt observed that there didn’t seem to be any way for Apple to significantly increase its market share given Windows’ lead and the strong network effects in the market.

Jobs didn’t agree or disagree with Rumelt’s argument. He just smiled and said, “I am going to wait for the next big thing.”

Waiting for the next big thing isn’t always a winning strategy. But it was a strategy that leveraged Apple’s strength — as a small, niche producer, it could move quickly and pounce on any new opportunities. And, at that time, in that industry, it was a good strategy.

Luckily, you don’t have to get things completely right — your strategy just has to be more right than your rivals’.

Things to watch out for

Attempts to engineer growth

The idea that growth is good has become “an article of almost unquestioned faith” in business. And it’s true that it’s a good sign when demand for your firm’s superior products or skills increases.

But growth is the outcome of a successful strategy. Attempts to engineer growth, such as by acquisition, rarely create value. To buy another company, you usually have to pay a premium of around 25% plus fees above its market value. Moreover, adding more products and projects makes it harder to maintain focus and coordination.

So unless you can buy a company for less than its value, or unless you are specially placed to add more value to it than anyone else, acquisitions won’t create value.

Inertia

Inertia is an organisation’s unwillingness or inability to change. New upstarts often succeed thanks to the inertia of incumbents. But success leads to laxity and, over time, the nimble upstarts become bloated and inert themselves.

A very powerful resource position produces profit without great effort, and it is human nature that the easy life breeds laxity.

Rumelt describes 3 types of inertia:

- Routine. Routines that describe “the way things are done” limit the scope of possible actions and shape managers’ perceptions. Routine inertia can be fixed by getting top management’s perceptions to change.

- Culture. Organisational culture cannot be changed quickly or easily. In general, changing a group’s norms requires replacing the alpha member (the highest status member from which others take their cue) with someone who expresses different norms and values.

- By proxy. Inertia by proxy occurs when a business is slow to change because it wants to hang onto existing profit streams and its customers are slow to change. For example, established banks may not increase their savings interest rates even when other banks do, if most of their depositors have inertia and are unlikely to switch banks.

Example: Routine inertia following airline deregulation

Before the US airline industry got deregulated in 1978, long-haul routes were the most lucrative and short-haul routes generated losses. Airlines only flew short-haul because regulators forced them to.

Rumelt predicted that, with deregulation, airfares would shift to match routes’ actual costs — i.e. short-haul fares would rise and long-haul fares would fall. This was what ended up happening.

But the inertia of routine meant that the major airlines’ planning, pricing and marketing strategies remained focused on long-haul routes, assuming (wrongly) that they would remain as profitable as they’d always been. So, for several years after deregulation, the old, major airlines kept losing money by targeting long-haul routes while the short-haul carriers made a profit.

Entropy

Entropy measures a physical system’s degree of disorder. The second law of thermodynamics states that entropy always increases in an isolated physical system. Rumelt extends this analogy to business. Over time, organisations naturally grow less organised and focused unless they are properly managed. This is what distinguishes competent from incompetent management — good leaders deliberately work to counteract entropy.

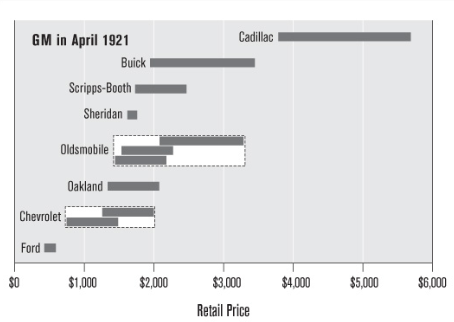

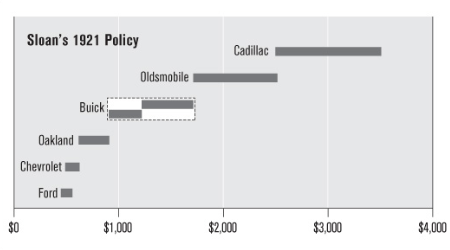

Example: Entropy at General Motors (GM)

In 1921, GM produced 10 different lines of cars. Many of these overlapped in price ranges and competed with each other in the mid-range of around $2,000. Meanwhile, it did not have a single car that competed with Ford’s $495 Model T.

Alfred Sloan, the vice president of operations, led a study of GM’s product lines. He recommended decluttering the product line so that customers easily understood where each car stood in relation to GM’s overall product line. This new policy dramatically reduced intra-company competition.

But by the 1980s, this clear delineation between product lines had faded away and models again clustered around the mass-market range. In a decentralised company, this is bound to happen as each unit tries to increase its market share — even if that comes at the expense of another unit in the same company. Management’s job is to coordinate efforts and direct competitive energy outward, not inward.

How to think like a strategist

Strategy requires analysing unstructured information

It’s not quite correct to describe strategy as being a choice or decision as leaders rarely get a clear set of options to choose from. Effective strategies are constructed more than chosen.

Working out a company’s actual strategy can require some work. It’s not necessarily what the CEO or some other executive says it is. To work out a company’s actual strategy, you have to do your own analysis and pull together various bits of unstructured information. This is hard and time-consuming. You’ll need a rich knowledge of the facts as well as the skill of logical thinking.

Example: Crown Cork & Seal

Crown makes metal containers such as cans. The industry is terrible. Cans are essentially indistinguishable from each other, so it’s hard to stand out. Each beverage company usually has at least two can suppliers, so there’s very direct competition. Plus, can-makers often set up plants to supply a particular customer, so they’re captive producers. The major can companies only earn return on assets of around 4 to 5%.

Despite being smaller and having higher per-unit costs, Crown manages to beat the big 3 can-making companies by a large margin. How is Crown so successful?

Crown is one of the oldest business school case studies. The conventional wisdom was that Crown specialised in containers for hard-to-hold products like aerosols and carbonated soft drinks. This is true, but not very useful.

Rumelt uses the Crown case study in a class to illustrate the importance of doing your own analysis. To identify the company’s strategy, he looked at how the company’s policies differed from the norm and then tried to work out why. What were these policies coordinated to achieve?

In Crown’s case, some unusual features were:

- Crown had smaller plants, likely with higher per-unit costs;

- none of Crown’s plants were captive—each had at least 2 customers and some had waitlists;

- they emphasised technical assistance;

- Crown also responded rapidly to customer needs.

What kind of customer needs these things?

The answer was that Crown’s strategy was to do short runs. While the major can-makers accept long runs to avoid costly changeovers, Crown does the opposite and focuses on short runs. Runs may be shorter because the customer is smaller (hence the emphasis on technical assistance — smaller companies don’t have the internal expertise); or it’s a rush order to cover seasonal or unexpected demand (hence the rapid response); or it is a newer product.

Even though Crown’s per unit costs were higher than its competitors’, it could charge higher prices because it avoided the captive squeeze. Its strategy was one of focus—it coordinated its policies to produce power and applied that power to an underserved segment of the market.

The logic of Crown’s strategy was only visible after Rumelt’s analysis. It was not visible in the company’s own self-description, nor in what Wall Street analysts said about it. The strategy wasn’t a secret, but it took some work to fit the pieces together.

Even if you do the work, you may not be able to find the inner strategic logic for every business. The truth is that many organisations, especially large ones, don’t really have strategies. As noted above, strategy is ultimately about focus and choice most complex organisations choose to spread, rather than focus, their resources.

New strategies are like hypotheses

Being a good strategist requires thinking like a scientist. The business world is much less rigorous than the world of science. Executives often choose a course of action based on their gut and no one ever knows if it was the right choice.

By contrast, scientists start with what they know and then conduct experiments to discover new knowledge. In the same way, we can treat a new strategy as a hypothesis and test it out. As results appear, we can learn what works and adjust accordingly. Good strategy work is empirical.

Strategies won’t always work, just like hypotheses won’t always pan out. In a changing world, good strategy must involve some new idea or theory. A good strategy is an educated judgment about what will work, but there are no guarantees.

Be aware of your own cognitive limits and biases

We all have cognitive limitations and biases. To be strategic, you just have to be less biased than others and recognise when your instincts are likely to lead you astray. Our instincts tend to be particularly bad at judgments involving the likelihood of events; our own competence; and cause-and-effect relationships. Being able to think about your own thinking is a personal skill more important than any particular strategy concept, tool, or framework.

Most people usually solve problems by using the first solution that pops into their heads. They then spend their efforts justifying it rather than questioning it, and overlook the better ideas that may still be out there. In many simple, low-stakes situations, this is fine. But strategy, almost by definition, is about very difficult and important issues, which require deeper analysis.

To scrutinise his own ideas, Rumelt uses a mental trick where he calls upon a virtual panel of experts, comprised of people whose judgments he values. He engages in internal mental dialogues with them to critique his own ideas and generate new ones. This trick works well because humans are naturally better at recognising and understanding personalities than at applying conceptual frameworks.

The kernel can also help with this, because it reminds you to push past your initial insight and think carefully about all three elements. Flashes of insight are usually localised—they may strike in the form of a diagnosis, guiding policy, or action, but not all three.

My Review of Good Strategy, Bad Strategy

Good Strategy, Bad Strategy should really be mandatory reading for people in top leadership positions. Many examples of bad strategy matched my personal experiences and I enjoyed Rumelt’s low-key snark on them. I suspect he was getting years of frustration at bad strategy off his chest.

Rumelt’s experience is pretty impressive and he really seems to know what he’s talking about. He claims to have started studying business strategy in 1966, well before it became popular and, throughout the book, he describes many of his own experiences as a consultant to both megacorps and governments. I also appreciated how Rumelt didn’t oversell or over-generalise. For example, in his story about Steve Jobs saying waiting for “the next big thing”, he is careful to point out that waiting for the next big thing is not a general formula for success. It was just the right one at that moment, in that industry, with many new technologies around the corner.

I have to admit that I was sceptical that a book could teach me much about something as vague and amorphous as ‘strategy’, but the kernel framework brought some valuable structure and clarity to the topic. Beyond that, Rumelt’s underlying advice still appeared to be sound, though I found the structure messier and repetitive (which is why I’ve adopted a different structure in this summary).

At times I found some of the case studies a little dry, because I didn’t care to know all the details about whatever particular business. But this was kind of the point. In the real world, you don’t get all the relevant facts nicely distilled and set out for you. In the real world, you have whatever unstructured information you have. A key part of strategy is in making sense of that information, working out which pieces are relevant, and figuring out how to get any further information that you need.

Let me know what you think of my summary of Good Strategy, Bad Strategy in the comments below!

Buy Good Strategy, Bad Strategy at: Amazon <– This is an affiliate link, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through it. Thanks for supporting the site! 🙂

If you enjoyed this summary of Good Strategy, Bad Strategy, you may also like:

8 thoughts on “Book Summary: Good Strategy, Bad Strategy by Richard Rumelt”

This was great!

One thing I wondered about when I read this review and the originally the book was the proportion of good strategies that came about through deliberate thought.

Clearly Rummelt is advocating for the idea that through deliberate thought, one can craft a good strategy. But especially with businesses, how much of it is just descriptive after a much more messy, evolutionary process, after the fact?

So we have 1000 businesses, each somewhat randomly try things, and at the end of the day 1 of them is the most successful. If we then breakdown what they did, it will look like a very clever strategy. But how often did that actually arise from doing work of the sort Rummelt advocates, vs just a random evolutionary process?

(Rhetorical question – probably impossible to answer)

This is something I definitely thought about too. How much of this is retroactively looking at business successes and trying to fit their actions into a “good strategy” model? Humans love to look for causality.

Thanks! Yeah, you make a really good point and I think it’s always good to be sceptical of post hoc explanations as to why a particular course of action succeeded or failed.

One thing I appreciated Rumelt clarifying was that “bad strategy” isn’t a mere miscalculation, but the active avoidance of confronting challenges and making tough decisions. In which case, why bother with strategy at all? I also liked that Rumelt wasn’t too prescriptive about what a “good strategy” is (the kernel is pretty barebones and flexible).

I agree with your point that real life, things are messy and success involves a lot of randomness – and you rightly point out that most of his examples of good strategies seemed to come about through deliberate thought.

My impression is that applying deliberate thought and reasoning will at least increase the chances of success. To take your 1000 businesses example — say 100 of them apply good strategy while 900 of them do bad or no strategy. Perhaps 33% of the no strategy group will succeed due to random chance, while the success rate among the good strategy group is 50%. So if you then look at the successful companies, far more would have employed no strategy (300) than a good strategy (50). But good strategy would still have been worth it.

Of course, I’m making up these numbers and it’s possible that the success rate for good strategy remains 33% (or even lower, if you think good strategy is counterproductive!). But that seems implausible to me. Even in areas of great uncertainty, I generally think applying some deliberate thought and reasoning improves the chances of success. And if bad/no strategy is very common, I’d expect the gains from applying deliberate thought to be higher.

Really interesting topic. It’s cool strategic thinking systemically broken down like this. It clearly takes a lot of observational awareness and critical thinking to devise good strategy. And of course, one needs the courage to confidently carry it out!

Though, I’m still left wondering how to evaluate the effectiveness of one’s strategy. The common pitfall to avoid is conflating the outcome from the process, which is mentioned in this summary. I do think it would be nice to see examples of good strategy that did NOT pan out, just to hammer this distinction home

Good point about it still being hard to evaluate how effective one’s strategy is. Even if you followed Rumelt’s approach and applied the ‘kernel’, you could come up with a dozen different strategies for the same situation given how flexible the kernel is. I liked the example with Stephanie’s grocery store, where Rumelt admits Steph couldn’t be sure the guiding policy she chose was necessarily the best one (or even a good one), but it helped make her efforts coherent.

My overall takeaway was more “To avoid doing bad strategy, you need to consider A, B, C at a bare minimum” than “Do A, B and C and then you’ll succeed”.

Yes I really liked that example too My takeaway is that deciding between strategy A vs strategy B doesn’t matter so much as having a strategy at all, something to direct your efforts towards

Thank you for the review, I enjoyed it and found the way you organised its contents helpful. I look forward to picking up the book!

Thanks, glad you found it helpful!