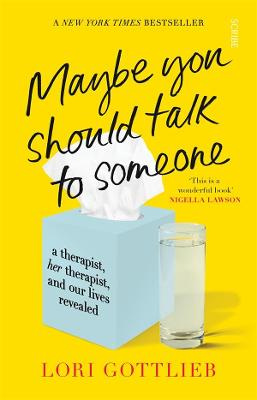

My latest summary is for Maybe You Should Talk to Someone, a book that gives us a peek into the therapy room, and the lives of five different people receiving therapy. One of those five is the author, Gottlieb, and we see her perspective both as a therapist and as a patient.

The book is non-fiction, with patients’ identifying details altered. However, Gottlieb writes in a narrative format more familiar to fiction. She also intersperses her thoughts and observations on therapy and life throughout the book. In that way, its structure is somewhat similar to Evicted by Matthew Desmond.

This summary is therefore a bit different from my normal summaries. I first briefly outline the stories in Maybe You Should Talk to Someone (I’ve added spoiler warnings below as appropriate). Then I try to group Gottlieb’s insights along some general themes. However, my summary is not an accurate reflection of the time spent on each of these in the book. The main focus of the book is on the stories, with Gottlieb’s observations being peripheral. I reverse that focus in this summary.

Buy Maybe You Should Talk to Someone at: Amazon | Kobo (affiliate links)

Key Takeaways from Maybe You Should Talk to Someone

It’s very difficult to summarise the key takeaways of Maybe You Should Talk to Someone. But if I had to take a stab, I would say the key takeaways for me are:

- Therapy is about helping people understand themselves and take responsibility for their own lives.

- The therapist’s role is to guide patients, not to tell them what to do.

- The reason a therapist can help a patient isn’t because they’re just “better at life” than the patient. Rather, a therapist helps by providing an objective perspective, bringing insights from their experiences with other patients, and giving the patient a safe, non-judgmental space to work through their issues.

- Therapy involves changing people’s relationships with the “past”. We can’t alter the past, but we can stop fantasising about a better past and do what we can with the present.

- Change is an inevitable part of life.

- Many of us resist and fear change, even when it is positive, because our current situation feels more familiar and safer.

- It’s never too late to change, but it’s up to us to change our own lives. Sometimes what we need to do is just get out of our own way.

- We all suffer pain and loss:

- There is no hierarchy of pain. Problems that may appear trivial are, at their core, often driven by a deeper fear or emotion.

- “Closure” is a bit of myth. If you’ve had a deep loss, you may well feel the pain many years afterwards. Some days will be worse than others. The aim isn’t to make the pain go away, but simply to integrate it into your life so that you can keep living.

- Therapists are human.

- Therapists have their own problems, too.

- Sometimes therapists don’t know what to say in a therapy session. Therapy is an art, and therapists constantly have to weigh up how best to help a patient.

- It can be difficult to see a patient as they truly are. Patients generally want to be liked by their therapists, and so may hide their flaws and give skewed accounts of events. But patients often place unrealistic expectations on their therapists.

Detailed Summary of Maybe You Should Talk to Someone

The Stories

Maybe You Should Talk to Someone contains 5 stories. The stories feature:

- The author, who turns to therapy after a bad breakup.

- John, a TV executive, who initially comes off like an asshole.

- Julie, a college professor in her early thirties, who receives a terminal cancer diagnosis.

- Rita, a lonely 69-year-old woman, who presents with depression.

- Charlotte, a 25-year-old woman, who feels anxious and bored and drinks a lot. Her story is relatively minor and not particularly interesting so I don’t cover it further.

The author’s story

Gottlieb’s boyfriend breaks up with her unexpectedly. The reason he gives is that he doesn’t really want to have kids around anymore, as his kids are about to leave the nest but Gottlieb’s son is still very young. Gottlieb takes this quite badly and seeks therapy herself.

She tries to find a male therapist who will essentially tell her that she’s right and that her ex-boyfriend is a “sociopath”. But her therapist, Wendell, doesn’t give her that. Instead, he works with her and, over time, we find out what is really bothering her.

It’s interesting to see how Gottlieb observes her own behaviour as a patient, in light of her own experience as a therapist. At one point, Wendell tells her that her feelings don’t have to mesh with what she thinks they should be, and Gottlieb realises she’s said the same thing to her patents many times. Coming from Wendell, however, she feels like she’s hearing those words for the first time.

Gottlieb is also a deliberately unreliable narrator. It’s only well into the book that she reveals some important facts that she’s been hiding from us. No doubt this is intended to mirror the way many patients (like John) reveal pertinent facts only after months of therapy.

John’s story

John’s a very successful Hollywood scriptwriter, who thinks he’s surrounded by idiots. He secretly starts going to therapy due to stress and difficulties with his wife. Rather than admitting to going to therapy, he jokes about how he tells others that Gottlieb is his mistress. It’s almost comical how rude he is, ordering food and getting it delivered to his therapy session.

Julie’s story

Julie is a likable 33-year-old college professor, who receives a cancer diagnosis after returning from her honeymoon. She and her new husband are forced to come to terms with this, and they struggle with decisions over whether to start a family as they’d always dreamed.

At one point, Julie decides to work as a weekend cashier at Trader Joe’s. When Gottlieb and her son run into Julie at Trader Joe’s, they see her thriving, full of joy and moving her line along efficiently to boot.

Rita’s story

Rita is 69-years-old when she starts therapy. She tells Gottlieb that she plans to end her life if it doesn’t improve within a year. Rita’s been divorced 3 times and has 4 estranged adult children. The one thing she has going for her in life is her art. She chalks her sad circumstances up to her bad choices in the past.

Her first husband, Richard, was a charming lawyer… until their first child was born. Then he started working late, drinking, and beating her and their children. Rita wanted out but felt she had no choice but to stay. She had dropped out of college to look after the kids so and couldn’t bear the thought of looking after 4 kids by herself and working a dead-end job.

Rita started drinking, too. She confesses her shame at not defending her children, instead going into another room while Richard beat their children.

Gottlieb’s observations on therapy

The life of a therapist

- Since therapists work alone, they don’t have the benefit of others’ input. They do hold group consultations with other therapists to get others’ views, objectivity, etc.

- Therapists frequently feel uncomfortable when they run into their patients outside work. A patient may feel surprised when they see their therapist in a situation that suggests they don’t have their lives completely together (e.g. crying, arguing with a spouse), and lose respect for them. One of Gottlieb’s colleagues has even lost a patient that way.

- When a patient dies, their therapist has to grieve alone. Even if they attend the funeral (which they often won’t), they have to be mindful of confidentiality, which doesn’t end on death. For example, if someone asks how they know the deceased, they can’t say they were the therapist.

The therapist’s perspective

- Usually, therapists let their office phones go to voicemail, so patients don’t feel rejected if they call during a crisis and the therapist only has a few minutes to talk.

- Therapists tend to sit close to the door in case things escalate and they need to escape.

- Instead of being neutral and suppressing their feelings, therapists try to be conscious of their un-neutral feelings and biases and use them to guide the therapy. The way a therapist sees or feels about a patient may well be how other people in the patient’s life see or feel about them.

- It’s common for therapists not to know what to say at some point during therapy.

- A therapist will occasionally have a complicated reaction to some new information and need more time to understand it. They are taught to hold off on doing anything for now and get consultation from others.

- A therapist will usually be several steps ahead of their patients, simply because they are able to take a more objective, outside view. Sometimes they will store up a question or statement, waiting for the right moment to float it. Therapists constantly weigh up when to support their patient (building trust) and when to confront them (get to the real work so the patient can improve).

- Therapists also struggle to decide what personal information to disclose to their patients. Sometimes self-disclosure can help connect with patients. But if the patient views the self-disclosure as inappropriate or self-indulgent, they may feel uncomfortable.

Finding a therapist

- Finding a good therapist can be hard. Most people aren’t comfortable going around asking for recommendations. People may also be reluctant to give recommendations, if they don’t want others to know they go to therapy.

- Gottlieb suggests going to PsychologyToday.com and looking through profiles in your area.

- It may pay to try a few different therapists to find one you “click” with. Studies show that clicking with your therapist matters more than their training, the kind of therapy they do, or the type of problem you have. For example, there are therapists who specialise in cancer patients, but Julie prefers to go to Gottlieb.

- Finding a therapist is even harder for therapists. Ethical constraints meant that Gottlieb had to find a therapist she doesn’t know.

The therapy process

- At the start:

- Patients come to therapy with a presenting problem. Usually that problem is just one aspect of a larger problem, or even a complete red herring.

- In the early sessions, the focus is just on making patients feel heard and understood, rather than for them to gain any insight or make changes.

- Gottlieb will often ask patients to recount their past 24 hours in as much detail as possible. She can then get a good sense of the people in their lives, how connected they are, how they choose to spend their time, etc.

- Therapists also commonly inquire about their patients’ parents. They do this not to blame, judge or criticise the parents, but to understand how their patients’ early experiences shaped who they are.

- Understanding the issues:

- The sessions that tend to be the most revelatory are the ones where patients don’t come with a crisis or agenda. Instead, there is space for their minds to wander.

- Though it’s a bit of a trope, silences can really unearth the important things. Talking can be a distraction that keeps people away from their emotions. Even great joy is sometimes best expressed through silence.

- When a therapist sees the “heart” of the problem, they won’t take the patient straight there. Instead, they nudge patients to arrive there because people take a truth more seriously when they slowly get understand it on their own.

- Improvement:

- Patients have to tolerate some discomfort for therapy to be effective. Therapy requires people to see themselves in ways they normally choose not to. A therapist will constantly calibrate how they’re going. If they hit a nerve, they’ll back off slightly but will keep pressing gently at it. At the core is usually some form of grief.

- Therapy is most effective when the crisis has passed and people start getting better, as this is when people are less reactive and better placed to engage. Unfortunately, people sometimes leave when their immediate symptoms lift, which is when the work is just beginning.

- It’s common for patients to want to be told what to do, believing their therapist would know the right answer. One reason is so that they don’t have to take responsibility for their decisions if they don’t work out. But Gottlieb thinks people actually resent being told what to do – even if they ask for it, and even if the advice seems pretty benign. Ultimately, people want agency over their lives and the therapist wants them to be independent. People can also often misconstrue what their therapist says.

- Flight to health:

- Flight to health is a phenomenon where the patient thinks they’re suddenly over their issue. It’s especially common when there’s been a break in the therapy. The patient thinks that, since they did fine in the break, they don’t need therapy anymore.

- Sometimes the change is genuine. Other times, it’s just that the patient can’t tolerate the anxiety involved in working through their issues.

- People also commonly mistake feeling less for feeling better.

- Termination:

- The final stage of therapy is “termination”. People tend to remember experiences based on how they end, and the termination stage should give patients the experience of a positive conclusion.

- One litmus test of whether a patient is ready for termination is whether they carry the therapist’s voice in their head, applying it to situations and eliminating the need for therapy. For example, Gottlieb describes how she’d internalised Wendell’s voice and his ways of questioning and reframing situations, sometimes having entire conversations with him. [I sort of understand, but this sounds odd to me.]

- Sometimes people just drop out of therapy because it makes them feel accountable when they don’t want to be.

Therapy sessions

- A therapy session has a certain flow or rhythm. Therapists try to open patients up in their sessions, and put them back together towards the end. Putting people back together takes around 3-10 minutes. So even if the therapist discovers something worth digging into near the end, they’ll park it for next time.

- It’s not uncommon for a patient to go through a session talking about pretty mundane stuff, then blurt out something important right at the end. Gottlieb calls these “doorknob disclosures”.

- Remote sessions are nowhere near as good as in person. The therapist can notice a lot more in person – e.g. a foot shaking, a subtle facial twitch.

- Walking out of therapy is not uncommon, particularly in couples therapy.

- Sometimes people don’t show up to “punish” the therapist and send a message that they’re upset.

The therapist-patient relationship

- Patients can place unrealistic hopes and demands on their therapists. Many hope that the therapist can help them find a cure quickly. But it can take a lot of time to get to know patients since they are complete strangers at the start.

- It’s common for patients to want to be liked by their therapists.

- Many patients secretly want to be their therapist’s only, or at least “favourite”, patient. They can be unreliable narrators, trying to hide their vulnerabilities and weaknesses. This can frustrate the therapy, as therapists need to see patients as they truly are for therapy to work.

- Patients often wonder if they bore their therapists with their mundane lives. Gottlieb says she doesn’t think her patients’ lives are boring at all. They’re only boring when they refuse to share and open up.

- Sometimes patients develop romantic feelings towards their therapist.

- This is called romantic transference and is apparently quite common.

- Since the therapist pays undivided attention to the details of your life, knows you, accepts you, and supports you, it’s easy to conflate that intimacy with the intimacy of romance or sex.

- Therapists don’t need to like their patients:

- They can still do a good job if they don’t like their patients. Therapists just need to be warm, non-judgmental, and accepting.

- A “high-functioning patient” is therapist code for “good” patient.

- Many patients feel shaken when a therapist is late for a session. It can bring up old feelings of distrust or abandonment.

- Patients can accidentally let slip things that they’ve found out (often deliberately) about their therapists’ lives. Gottlieb says this knowledge can contaminate the relationship and cause patients to edit what they say in their sessions.

Gottlieb’s thoughts on people and life

It’s fascinating to hear Gottlieb’s perspectives on people and on life more generally. Of course, her perspectives are just one person’s, and she may well be wrong about some things. Yet very few people will have as much experience as Gottlieb’s had, hearing the deepest secrets, fears and insecurities of so many people from different walks of life. So I’m inclined to place some weight on her views.

Understanding

- We all have a deep desire to be understood. In couples therapy, “you don’t understand me” is a more common complaint than “you don’t love me”.

Therapy is about self-understanding

- Many people go to therapy trying to understand others (“why did he do this?”). Instead therapists try to get people to be more curious about understanding themselves.

- Gottlieb contrasts therapy with counselling, which is about getting advice.

- Most people are afraid of delving deep into their own thoughts and feelings, and don’t want to do it alone. With therapy, they have somebody to go into those depths with.

- Our biggest problem is usually that we don’t know what our own problem is. So we keep doing the same things that guarantee our own unhappiness over and over again. Once we identify our feelings, we can choose what to do with them. But if we push them away, we get lost. And if we suppress them, they can escape at an unexpected time.

- Part of getting to know yourself is to “unknow” yourself, letting go of the old stories we tell that limit us.

Feelings can be tricky

- Children are emotionally free, at least for a while. They can cry, laugh, or have tantrums unselfconsciously. Gottlieb explains that part of why she’s going to therapy is trying to free herself emotionally again.

- Sometimes people can’t identify their feelings because their parents discouraged them growing up. For example, their parents may have told them they shouldn’t feel sad or angry. Or their parent may have distracted them whenever they did feel sad.

- Men tend to be worse at identifying and talking about their feelings, because society pressures men to keep up their emotional appearance. Gottlieb observes that when men tell her how they feel in therapy, she’s almost always the first person they’ve said it to.

- Women are more likely to confide in others. But almost every woman Gottlieb has seen apologises for her feelings too – especially tears.

- Anger can cover up other feelings.

- It’s an outward-directed emotion, and many people resort to it because it feels good and sanctimonious. [The Courage to be Disliked by Kishimi and Koga made the same point.]

- Anger often covers up feelings like: fear, envy, loneliness, insecurity. Understanding and listening to these deeper feelings can help manage anger and make you feel angry less often.

Defence mechanisms help us deal with unacceptable feelings

- People use defence mechanisms to deal with feelings like anxiety and frustration, though they aren’t aware of that in the moment.

- Some defence mechanisms are “primitive” and others “mature”.

- Examples of defence mechanisms include: denial, rationalisation, reaction formation displacement and sublimation.

- Reaction formation is expressing the opposite of an unacceptable feeling. For example, a closeted gay man making homophobic slurs.

- Displacement is a neurotic defence, neither primitive nor mature. It involves shifting a feeling from one person onto a safer alternative. For example, if someone’s boss yells at them, they might come home and yell at their family.

- Sublimation is a mature defence mechanism. It is when someone takes a potentially harmful impulse and turns it into something less harmful, or even constructive (e.g. channelling aggressive impulses by taking up boxing).

Common insecurities

- Everyone who goes to therapy worries that they’re not “normal” or “a good person”. Therapy aims for self-compassion (am I human?) rather than self-esteem (am I good or bad?).

- People who can’t say “no” are usually worried about others’ approval. In contrast, people who can’t say “yes” usually lack trust in themselves. They worry they might mess things up. However, sometimes what seems like saying “no”, is actually an inverted way of avoiding saying “yes”.

Loneliness and intimacy

- Gottlieb thinks that almost all her patients had this common element of loneliness, a desire for stronger human connection.

- Intimacy comes with pain. Even in the best possible relationship, you’ll sometimes get hurt, and you’ll sometimes hurt the other person.

- But the great thing about a loving intimacy is that there is room for repair.

- Some people never learned in their childhoods to take responsibility for mistakes and learn from them (often because their parents didn’t teach them that). Such people can find it harder to tolerate and recover from ruptures in their adult relationships. It can take them time to learn that a rupture doesn’t signal the end of the relationship. And even when it does, that they can survive it.

- Love later on in life still exists. It tends to be especially forgiving, generous, and urgent. The heart is just as fragile at age seventy as at age seventeen. Falling in love never gets old, no matter how jaded you are.

Loss

- “Silent losses”, like miscarriages and breakups, are less tangible to other people. Unlike losing a child or spouse, people will tend to assume you’ll move on relatively quickly.

- Losses tend to have multiple layers. There’s the actual loss and the underlying loss (what it represents). For many people, a breakup or divorce is only partially about losing the other person. Often it’s also about failure, rejection, betrayal, fear of the unknown, unmet expectations.

- There are many things we take for granted until we lose them, even things that frustrated us. Gottlieb notes that many women told her that they hated getting their menstrual periods but grieved losing them when they reached menopause.

Suicide

- Suicidal thoughts are common with depression, but most people never act on them.

- People are most likely to commit suicide when they start getting better. They’re not so depressed that eating or dressing seem like monumental efforts, but they’re still in enough pain to want to end it.

- Bringing up suicide doesn’t “plant” the idea in someone’s head, as is commonly believed.

- When suicide does come up, the therapist has to weigh things up and assess if there is a real danger. If they think there isn’t, they monitor the situation closely and work on the depression.

Common myths

Closure

- The well-known 5 stages of grief (denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance) were originally conceived in the context of terminally ill patients coming to terms with their deaths. Decades later, the model became used for grief more generally. But for those who keep living, the idea that they have to get to “acceptance” can make them feel worse.

- Instead of the 5 stages, grief psychologist William Worden came up with tasks of mourning. The fourth task is to integrate the loss in your life – creating an ongoing connection with the person who died while also finding a way to keep living.

- Gottlieb points out there is no endpoint to love and loss. People seek “closure”, where they stop feeling pain. But you can’t mute pain without also muting the joy.

- Feelings come and go. You might feel fine most days, but then a trigger (a particular day, a certain song) reminds you of your loss and you’ll feel the pain again.

Forgiveness

- True forgiveness can serve as a powerful release that helps you move on. However, sometimes people feel like they have to forgive someone to get past a trauma. Well-meaning people keep tell them that until they can forgive, they’ll hold onto the anger. Therapists call this “forced forgiveness”.

- The patient may then feel pressured to forgive. And if they can’t bring themselves to do it, they may start thinking that they’re not compassionate enough or something.

- Gottlieb thinks you can move on and have compassion without forgiving someone who has wronged you.

- Sometimes we ask others for forgiveness, to avoid the harder task of forgiving ourselves. It’s a form of self-gratification.

Deathbeds

- Transformative deathbed conversation tend to be fantasies. People hope for peace, clarity, understanding and healing.

- Instead, deathbeds usually involve fear, confusion, drugs and weakness.

Personality disorders

- Personality orders lie on a spectrum. A person may have traits of a personality disorder without meeting the criteria for an official diagnosis.

- The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders lists 10 types of personality disorders, divided into 3 clusters:

- Cluster A (odd, bizarre, eccentric) are the paranoid, schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders.

- Cluster B (dramatic, erratic) are the antisocial, borderline, histrionic and narcissistic personality disorders.

- Cluster C (anxious, fearful) are the avoidant, dependent and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders.

- Most patients in outpatient practice are in cluster B (though not so much the antisocial ones). Those in clusters A and C don’t tend to seek out therapy. Borderline types tend to pair up with narcissists, and that is a common pairing in couples therapy.

- As a therapist, Gottlieb tries to see the person’s underlying struggles and not focus too much on their “diagnosis”. Seeing everything through the lens of a diagnosis interferes with forming a real relationship.

Taking responsibility is key to improvement

- Many people come to therapy feeling trapped. Usually we’re the ones imprisoning ourselves. There’s a way out as long as we’re willing to see it.

- For example, patients often have an ideal scenario in mind, and think they can only be happy in that scenario. This kind of thinking causes us to pass up opportunities for joy.

- People often believe their problems are mostly external, so they don’t see the need to change themselves. Therapy helps people take responsibility for their own situations. It’s only once someone realises they can construct own lives, that they can generate change. [Sounds a bit like The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck by Mark Manson. But I was surprised to hear that people often see their problems as external. I expected that people with such a view wouldn’t attend therapy, since they probably wouldn’t think therapy could solve external problems.]

- A common theme in therapy is patients wanting other people to change, when those people don’t want to change (even if they say they do). For example, a patient’s boyfriend may not want to stop smoking pot all the time even if he says he does. In that case, the patient has to change instead and take responsibility for their own lives.

- We can choose our responses.

- Viktor Frankl, an Austrian psychiatrist, believed that people ultimately want to find meaning in their lives. Frankl was detained in a concentration camp for 3 years and, when freed, found out that his wife, parents and brother had all been killed.

- He wrote Man’s Search for Meaning, a treatise on resilience and salvation. It made the point that reactions are reflexive but responses are chosen. We can always choose our response. And it is our responses that lead to growth and freedom.

- Gottlieb thinks that Frankl’s ideas could be applied to every patient she saw.

Changing our relationships with the past (and future)

- Our pasts affect the ways we think, feel and act. But at some point, we have to accept that we can’t change the past and stop fantasising about a better past. We’ll get stuck if we keep trying to get our parents, siblings or partners to fix what happened in the past. Changing people’s relationships with the past is a “staple” of therapy.

- People start therapy thinking they’ll talk through things from the past but much of therapy is about the present – what they’re thinking and feeling day-to-day. [This reminded me of Adlerian psychology’s emphasis on the present, from The Courage to be Disliked.]

- Parental relationships evolve in midlife as people shift from blaming their parents to taking responsibility for their lives.

- Younger patients come to therapy to understand why their parents won’t act in ways they want.

- Older patients come to therapy to understand how to manage the relationship the way it is.

- Gottlieb thinks most parents did their best, regardless of how good that “best” was. While discussing Rita’s parenting regrets, Gottlieb comments that she wishes all adults had an opportunity to hear parents (not their own) open up, become vulnerable and give their versions of events. She thinks that once you hear that, you can’t help but come to a newfound understanding of your own parents’ lives.

- Our futures can block change as well. We create a “future” in our minds every day. When things in the present fall apart (like a relationship break-up), the future we had in mind also falls apart. If we keep trying to control the future, we remain stuck in place.

The Trans-Theoretical Model of behaviour change (TTM)

- James Prochaska developed the TTM of behaviour change in the 1980s.

- Research showed that people don’t just suddenly changes, but instead move through different stages:

- Stage 1: Pre-contemplation. At this stage, the person isn’t even thinking about changing. It’s similar to denial.

- Stage 2: Contemplation. The person recognises the problem and isn’t opposed to making changes (in theory) but can’t seem to do it. People often start therapy in this stage.

- Stage 3: Preparation. People procrastinate as a way to stave off change, because they’re reluctant to give up something they already have for something new and unknown.

- Stage 4: Action

- Stage 5: Maintenance. This is the goal, the point where the person has maintained the change for a significant period. While there may be relapses, by this point people can usually get back on track with some support.

People are resistant to change

- The nature of life is change and the nature of people is to resist change.

- When one person in a family starts to make changes, even positive ones, the other family members will often resist and try to maintain the status quo. For example, if an addict stops drinking, their family members may unconsciously sabotage their recovery, because the status quo involves having a “troubled person” in the family.

- People are attracted to familiarity. It’s why people with angry parents often end up with angry partners. Until they work through those complicated feelings with their parents, they keep getting drawn to the same “type”, which is often familiar but unhealthy.

Other interesting facts

- Since the 1990s, psychotherapy has been on the decline and drug therapy has been increasing.

- Gottlieb thinks that psychotherapy still works, just not fast enough for today’s patients who find it easier and cheaper to swallow a pill.

- Psychiatry is more about medication and neurotransmitters than people’s life stories. Clinical psychologists are the ones who do therapy.

- Older patients are underrepresented in therapy

- Most of Gottlieb’s patients are young or middle aged.

- Many older adults (as around Rita’s age) are sceptical of therapy. They grew up believing that they can just get through problems on their own. Moreover, the staff in lower-cost clinics tend to be younger (e.g. interns in their 20s), which can be off-putting to older retirees seeking help there.

- Medical students’ disease is an actual phenomenon, where medical students believe that they’re suffering from whatever illnesses they happen to be studying.

- Cherophobia is the irrational fear of joy (“chero” meaning “rejoice”).

- Touch is a deep human need. It can lower blood pressure and stress levels, and boost moods and immune systems. Babies can die from lack of touch and adults who are touched regularly tend to live longer. “Skin hunger” is the term used to describe a lack of touch.

- It’s not uncommon for parents to envy their children. The children might have more opportunities or financial stability than the parents had. In addition, they still have their whole lives ahead of them. While parents strive to give their children everything they didn’t have, they sometimes end up resenting them for it, without even realising it.

- Bucket lists help us procrastinate death. Most people’s bucket lists are long, as they imagine they have a lot of time left to tick off everything they want.

My Thoughts

The premise of Maybe You Should Talk to Someone sucked me in. Unless you’re a therapist, you’ll never know what goes on in the therapy room. Even if you’ve been to therapy, you might wonder what other patients talk about in therapy, and what therapists really think of their patients. The premise piqued my curiosity, and Gottlieb delivered.

Gottlieb’s writing style is easy and relatable. The stories themselves are engaging and involve a varied selection of life’s common problems – I found Julie’s story particularly touching. The book feels a bit like a chick flick and I see that ABC is turning the book into a TV series featuring Eva Longoria. Though I don’t mean “chick flick” in a derogatory sense at all, and I’m sure plenty of men can enjoy the book too. But it’s worth noting that, with the exception of John, the patients Gottlieb focuses on are all women.

Maybe You Should Talk to Someone probably made me think more about therapy more than I ever have. In turn, that has caused me to reconsider some of my old thoughts (okay, prejudices) about it. I think I’ve always kind of secretly believed that it was a bit indulgent – not that I’d ever say that out loud. In the TV Show Scrubs, Elliot once commented that her dad always believed that therapy was “for people with more money than problems”, which I found funny and, also kind of true.

Now I’m sure it’s true that poor people have less access to mental health services than richer people, as mental health tends to get less public funding than physical health services. It’s also plausible that poor people have more problems than richer people, as money can solve a lot of (external) problems, and lack of money often creates stress. But that of course doesn’t mean that richer people don’t have very real problems, or that they won’t derive much benefit from therapy. In that sense, I think some of the stigma around therapy (at least for me) was driven by the high price tag. If it was a lot cheaper – and therefore equally available to the poor and the rich – I think I would have viewed it differently.

Buy Maybe You Should Talk to Someone at: Amazon | Kobo <– These are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase. I’d be grateful if you considered supporting the site in this way! 🙂

Have you read this book? Disagree with my thoughts? Let me know what you think in the comments below.

If you enjoyed this summary of Maybe You Should Talk to Someone, you may also like: