In Not the End of the World, Hannah Ritchie uses data to explain why we can stand to be more optimistic about most of the environmental problems we face.

Buy Not the End of the World at: Amazon (affiliate link)

Key Takeaways from Not the End of the World

- The world has never been sustainable.

- While the environmental problems we face are enormous, there are reasons to be optimistic:

- Things are getting better on many measures. We are past the peak of population growth, air pollution, carbon emissions per capita, and deforestation.

- Technological progress has allowed us to decouple a comfortable lifestyle with harming the environment. Clean energy are now cheaper, crop yields higher, and meat and dairy substitutes are better than they’ve ever been.

- There is precedent for cooperation at regional and even global levels to solve environmental problems. We’ve solved acid rain, the ozone hole, and brought numerous wildlife species back from the brink of extinction.

- Doomsday messages do more harm than good:

- Often they’re just untrue, which undermines faith in science.

- Such messages can also make us feel paralysed and hopeless, rather than motivated into action.

- Optimism doesn’t mean complacency:

- Ritchie is cautiously optimistic about many environmental problems, and believes we can get close to the 2°C warming climate target (though we will almost certainly pass 1.5°C).

- We have the opportunity to be the first truly sustainable generation, in that we could meet the needs of the present generation without compromising future generations

- But we will have to change our current trajectory to get there.

I’ve set out in separate posts the solutions discussed in the book (both the good and bad), as well as environmental myths that Ritchie debunks. You can skip straight to them if you want.

Detailed Summary of Not the End of the World

Ritchie structures her book around 7 major environmental problems, devoting a chapter to each:

- Air pollution

- Climate change

- Deforestation

- Food

- Biodiversity loss

- Ocean plastics

- Overfishing

I significantly changed the structure of this summary because there’s a fair bit of overlap between the problems (especially 1 & 2, and 2, 3, 4 and 5), which are all interrelated.

The author’s background

Ritchie was the former Head of Research at Our World in Data a non-profit with an incredibly rich trove of data about global problems such as poverty, disease and climate change. It gained prominence during 2020 as it began publishing research and data on the Covid-19 pandemic, vaccinations, and testing.

While Ritchie was working towards her degree in environmental geoscience, she didn’t hear a single positive trend or solutions. She finished her degree thinking everything was getting worse.

Later, Ritchie realised this was completely wrong. Long-run trends for many environmental problems were gradually improving, but not in an exciting, headline-grabbing way. That’s what motivated Ritchie to write this book. Her aim is to give people an accurate view of environmental problems and what can be done about them.

The world has never been sustainable

Ritchie’s definition of “sustainable” comes from a landmark UN Report. It has two limbs:

- We must meet the needs of the present generation…

- … without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Focusing only on the second limb may lead you to think that the world has become unsustainable pretty recently.

But that’s not true. Ancient humans hunted hundreds of animals to extinction; cut down vast swathes of forest; and created tons of air pollution. The only reason they could do this without completely destroying the Earth was simply because populations were small.

Controversy exists because people often assume an unavoidable trade-off between the two limbs. Historically, that’s been true—we’ve made great progress on things like child mortality, life expectancy and extreme poverty—but it’s come at an environmental cost.

However, technological progress has enabled us to decouple a comfortable life from environmental damage, avoiding the trade-off between the two limbs.

Example: Decoupling in the UK

The UK has managed to decarbonise significantly without sacrificing quality of life. In Ritchie’s grandparents’ days, the average UK person emitted about 11 tonnes of carbon. Today it’s less than 5 tonnes.

Even though Ritchie isn’t nearly as frugal as her grandparents, her carbon footprint is lower because:

- the UK changed most of its energy sources from coal to renewables; and

- stuff has gotten more efficient (e.g. cars, light bulbs, appliances, and insulation).

We now have the opportunity to be the first generation to achieve true sustainability.

There are reasons to be optimistic

‘The world is much better; the world is still awful; the world can do much better.’

All three statements are true.

Past the peak

We’re past the peak on many measures of environmental destruction:

- Population growth;

- Air pollution;

- Carbon emissions per person; and

- Deforestation rates.

Population growth is falling

Some have argued that we need to limit global population growth. Ritchie, however, argues we should instead try to cut our environmental impact per person to zero, such that total impact will be zero regardless of how many people there are in the world.

Reducing the world’s population is not a viable solution because of how demographic change works. We’re already well past the peak of population growth and it will keep trending down for decades. The average fertility rate in the 1950s was around 5, while today, it’s around 2.4. [In most developed countries, fertility rates are below replacement — see e.g. The New New Zealand.]

We can’t really speed this up because people stay alive for decades. Even if the global fertility rate fell drastically from 2.4 to 1.5, the global population in 2100 would still be around 7 to 8 billion.

Air pollution is falling

When we burn stuff, it produces small particles that can get into our lungs and cause a bunch of health issues. Air pollution is one of the world’s biggest killers—the World Health Organization estimates it kills 7 million people every year.

Air pollution is not a modern problem as people have been burning stuff for millennia. Ancient Rome’s air was filthy. There’s even evidence of air pollution in Egyptian mummies’ lung tissue and hunter-gatherers’ teeth.

In fact, many of us are breathing the cleanest air in centuries.

The Great Smog of London

London was way more polluted in the 18th and 19th centuries than it is today. Thieves could even steal under cover of smog—it was that thick.

A particularly nasty event was the Great Smog of London in 1952. The city ground to a halt. People literally had to feel their way around outside to avoid obstacles. While the Great Smog lasted only 4 days, its fatalities are estimated to be around 10,000.

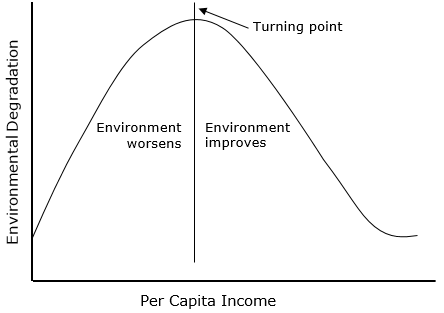

As countries get richer, they move along the “Environmental Kuznets Curve”. It’s a predictable path where pollution gets worse before it gets better:

When a country begins to move out of poverty, it burns more stuff — coal, oil, gas. Pollution rises.

But past a certain tipping point, people demand cleaner air. Governments respond by passing environmental regulations, which incentivise industry to find ways to pollute less. This is true even in non-democracies like China, which has now passed its peak of air pollution. Beijing, which used to be the poster child for air pollution, is no longer even one of the world’s 200 most polluted cities.

Rich countries like the UK and the US took 200 years to go through this rise and fall. Countries today can go through it much faster because the clean technologies already exist. Some of the poorest countries may even be able to skip the curve entirely.

Carbon emissions per person have peaked

Many countries have been able to decarbonise by switching to cleaner forms of energy. Carbon emissions per person have now peaked. Total emissions are still rising but have slowed significantly.

New petrol car sales also peaked in 2017. Electric car sales are growing rapidly, from only 4% of global sales in 2020 to 14% in 2022. In Norway and Sweden, the majority of new cars sold are now electric—88% and 54% respectively. The UK and China are around 20 to 30%. The US has been a relative laggard at only 8%.

There are still more existing petrol cars than electric cars, because people tend to run their cars for a decade or so, but we’ll eventually pass that peak, too.

Deforestation rates have peaked

Deforestation is bad because it destroys a huge amount of biodiversity and natural ecosystems that have built up over centuries or millennia. So deforestation in the tropics, which are thriving with biodiversity, is particularly bad.

We’ve lost around a third of our forests since the end of the last ice age. The main driver has always been agriculture—food lies close to the heart of almost all of our environmental problems. Of the various forms of agriculture, beef is by far the single biggest cause of deforestation, responsible for over 40% of global deforestation.

The good news is that forests began to make a comeback in rich countries as farming got more efficient and crop yields increased. Globally, deforestation rates peaked in the 1980s. Deforestation in the Amazon peaked a little later—Brazil managed to reduce deforestation by 80% in just 7 years under Lula da Silva’s first presidency.

But deforestation rates are still worryingly high in low- to middle-income countries, which tend to be located in the tropics and subtropics.

Technological progress and innovations

Historically, economic growth has come with more resource-intensive lifestyles. As humans got richer, we had larger carbon footprints, used more land, and ate more meat. This led to a “degrowth” movement, arguing that we should solve our environmental problems by shrinking the global economy.

However, Ritchie argues we’ll need economic growth globally if we want to end poverty. The world today is still far too poor:

- If everyone in the world lived on $30 per day with zero inequality, the global economy would need to more than double.

- If world inequality were more like Denmark’s (one of the most equal countries in the world), the global economy would need to increase 5-fold to lift everyone out of poverty.

Luckily, new technologies allow us to decouple a comfortable life from an environmentally destructive one.

Clean energy has gotten cheaper than coal

Solar and wind energy have gone from the most expensive forms of energy to the cheapest in just a decade:

- Prices of solar have dropped by 89%; and

- Prices of onshore wind have dropped by 70%.

Today, solar and wind energy are now cheaper than coal.

If you think about it, this makes sense—the price of fossil fuels and nuclear depends on two things: the cost of operating the plant plus the cost of the fuel (the coal, oil, gas or uranium). But since sunlight and wind are free, there’s no fuel cost for renewables. The only cost is for the technological components, which can get cheaper as technology improves. By contrast, it’s hard to make coal plants more efficient than they currently are.

Agricultural efficiency has improved

Over the past century, agricultural efficiency has improved drastically thanks to technological innovations like synthetic fertilisers and genetic breeding:

- Synthetic fertilisers. Before synthetic fertilisers, crop yields were very low, constrained by the amount of nitrogen in the soil. Once we figured out how to turn the nitrogen in the air into ammonia, a form usable by plants, it quickly became an essential part of agriculture. Without synthetic fertiliser, we’d only be able to produce around half as much food as we do today.

- Genetic breeding. In the 1940s to 1950s, Norman Borlaug spent 10 years trying more than 6,000 cross-breedings of wheat crops to try and improve their resistance to pests and disease. He managed to develop varieties that more than tripled crop yields for wheat.

Thanks to improved crop yields, we don’t need to cut down as many forests to grow the same amount of food.

Meat substitutes are getting more popular

Meat, especially beef, is pretty terrible for the environment in multiple ways. Plant-based substitutes are much better for the environment. [See Solutions in Not the End of the World for more on why this is.]

In recent years, the taste and cost of meat substitutes has improved considerably and their popularity has surged, especially among meat-eaters. Blind taste tests show that most people prefer hybrid burgers (part beef, part plant-based) to a 100% beef burger or a 100% plant-based alternative.

Meat substitutes still haven’t reached the stage where they’re considerably cheaper than meat—but when that happens, it will really be a gamechanger.

Aquaculture

Global seafood production has more than doubled since 1990, while the proportion of overexploited fish stocks has remained relatively constant.

The reason was we started aquaculture, which is basically fish farming. We now produce more seafood from fish farming than from wild ocean catch.

Infrastructure for disaster monitoring and response has improved

Death rates from disasters have plummeted over the past century:

- The annual death toll from disasters in the 1920s-1940s were often in the millions.

- Today, it’s usually between 10,000 to 20,000 (there are some outliers like the Haiti earthquake in 2010). Disasters haven’t gotten less frequent or severe. It’s just that our infrastructure has improved and we’ve gotten better at monitoring and responding to them.

However, this trend of lower death rates may not continue. There is a real risk that climate change in particular will reverse the trend, especially as it will disproportionately hurt lower-income countries with weak infrastructure.

Global and regional collaboration

There is precedent for countries successfully working together to solve environmental problems. Success stories include:

- acid rain;

- the hole in the ozone layer; and

- (some) endangered species.

Acid rain

Acid rain is caused by sulphur and nitrogen oxide emissions from fossil fuels and agriculture. In the late 20th century, it was a big environmental problem, killing forests, fish and freshwater insects. Even statues and monuments started dissolving.

After some strong resistance, the US and much of Europe brought in tight regulations. The solution was actually quite simple. By adding a reactant to a coal plant’s smokestacks, the sulphur dioxide could be stripped away. Sulphur dioxide emissions in the US fell around 95% from their peak, and 98% in the UK.

The hole in the ozone layer

Back in its day, the hole in the ozone layer was like climate change. It dominated the headlines and no country could solve it alone.

The problem was caused by humans emitting chlorine substances into the atmosphere, from things like refrigerators, air conditioners and aerosol sprays. This began to destroy the ozone layer, which absorbs ultraviolet radiation from the sun and protects humans and other animals against skin cancer.

For a long time, there was strong resistance and denial from industry and politicians. Scientists first pointed out the risks in 1970, but it wasn’t until 1987 that countries agreed in the Montreal Protocol to start phasing out ozone-depleting substances.

Once phase-out began, it was fast. Ozone-depleting substances fell 25% within a year, and 80% within a decade.

(Some) endangered species

Biodiversity has been falling and modern extinction rates are scarily high. One of the main causes of animal extinctions is not hunting, but by habitat destruction as we convert land to agricultural use.

But there are instances where we have pulled some species back from the brink with regulations and protected areas. Examples include African and Asian elephants, the blue whale, the European bison, the Eurasian beaver, the American bison and the southern white rhino. In the most extreme cases, populations have recovered from a few dozen to thousands or even hundreds of thousands. There are success stories all over the world.

The story is similar for some fish stocks. Overfishing was rampant in the 1980s and 1990s, but then monitoring technologies improved and fishing regulations got stricter. For example, between 1930s to the 2000s the southern bluefin tuna population fell from 8.5 million to less than 1 million. Today, they are still “endangered” but no longer “critically endangered”.

Doomsday messages do more harm than good

Doomsday messages do more harm than good because they’re often untrue, which undermines faith in science. (See Environmental myths debunked in Not the End of the World.) Such messages can also make us feel hopeless—if we’re already screwed, what’s the point in trying?

But Ritchie argues that giving up is indefensibly selfish. It comes from a position of privilege—the people who will be severely affected by our environmental problems don’t have the option to just ‘give up’.

[There’s research to support this idea that feeling positive about the future makes us more likely to engage in prosocial behaviours (especially if those future fantasies are juxtaposed with actual reality). See e.g. From feeling good to doing and Subjective well-being and prosociality around the globe.]

Optimism doesn’t imply complacency

Pessimism tends to sound intelligent while optimism tends to sound dumb. Indeed, blind optimism—the unfounded belief that things will just get better—is dumb. And dangerous.

Yet the world desperately needs more optimism. Recognising that positive trends exist doesn’t mean we ignore the problems. We can be conditionally optimistic, believing things will get better if we take action.

A sustainable future is not guaranteed—if we want it, we need to create it.

We need to step things up

The environmental challenges we face are massive. We will almost certainly exceed the 1.5°C climate target in the 2015 Paris Agreement, absent some major technological breakthrough.

But it’s not all-or-nothing. It’s not like the world will suddenly end once we pass 1.5°C. Even if we exceed the target, we still must do everything we can to minimise further increases. Every 0.1°C counts.

Ritchie is cautiously optimistic that we can get close to the 2°C target with effective climate policies:

- Without any climate policies, by 2100 we’d reach warming of 4 or 5°C at least. This is the path that most people still think we’re on;

- With the climate policies currently in place, we’re heading towards 2.5 to 2.9°C warming; and

- If each country followed through on its climate pledge, we’d get to 2.1°C by 2100. So we need to step up our efforts if we want to get below 2°C.

(See Our World In Data for the most up-to-date figures.)

Other Interesting Points

- The average annual carbon emissions for a person in Chad are about the same as an American’s emissions in just 1.5 days.

- When comparing land use for different forms of energy, we should also account for the land used to mine the materials, extract fuels, and deal with the waste. Once you do that, nuclear is the most land-efficient source, followed by gas. Solar panels on the ground are about twice as land-efficient as coal, and can be more efficient if you put them on roofs.

- The amount of land that must be moved to extract minerals for solar and wind energy (e.g. lithium, cobalt, copper, silver and nickel) is around 100 to 1,000 times lower than for fossil fuels:

- We currently extract around 15 billion tonnes of coal, oil and gas each year.

- We will need around 28 to 40 million tonnes of minerals for low-carbon technologies in 2040, at the height of the energy transition, according to estimates by the International Energy Agency. (Studies also show we will have enough minerals and won’t run out.)

- There’s no universal “paleo diet” that hunter-gatherers followed. It varies a lot by groups and by the time of year. In some months, meat might make up over 50% of of their diet while other months it might be less than 5%.

- The Great Pacific Garbage Patch stretches over an area 3x the size of France.

My Review of Not the End of the World

Not the End of the World discusses the various environmental problems we face in a balanced and constructive way. The writing style was easy to understand and approachable. Ritchie manages to correct many mistaken beliefs without, in my opinion, sounding condescending as she shares how she used to hold some of those beliefs too.

I found Ritchie to be a very careful and trustworthy author. Given her background at Our World in Data, it’s no surprise that she backs up her points with plenty of references. But she’s also good at treating her readers like adults—clarifying the terms she uses (e.g. life expectancy, sustainability), addressing obvious counterarguments (what about all the emissions rich countries offshore?) and confronting some of the weaker points of her own arguments (why should we care about biodiversity at all?). Ritchie is also nuanced in her writing, conveying a sense of hope and optimism while warning against complacency.

Environmental issues can easily become highly charged because whenever you talk about environmental destruction, questions around morality and who’s to blame inevitably crop up. For the most part, I think Ritchie manages to sidestep this by sticking to the facts, though I’m sure some will still take offence.

Overall, this book did make me more optimistic about our environmental problems, but I’m still not as optimistic as Ritchie seems to be. While it’s encouraging to hear how much cheaper clean energy has gotten, many of the solutions advocated in the book would still require:

- transfers from rich countries to poor countries; and

- the world to eat a lot less meat.

These two are very difficult nuts to crack. But, yeah, we should certainly try. And as Ritchie points out, even though we’ll probably pass 1.5°C, every 0.1°C still counts.

Let me know what you think of my summary of Not the End of the World in the comments below!

Buy Not the End of the World at: Amazon <– This is an affiliate link, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through it. Thanks for supporting the site! 🙂

If you enjoyed this summary of Not the End of the World, you may also like:

2 thoughts on “Book Summary: Not the End of the World by Hannah Ritchie”

An excellent summary, thanks.

Thanks, Christian!