In Principles: Life and Work, Ray Dalio reflects on his life and career, setting out the principles that helped him succeed and become one of the wealthiest people in the world.

Estimated reading time: 25 mins

Buy Principles: Life and Work at: Amazon (affiliate link)

Key Takeaways from Principles: Life and Work

Why Principles?

- Principles allow you to systemise your decision-making and operate consistently.

- When you can explain your principles, you can also debate them with others and reflect on and refine them.

Life Principles

- Understanding the cause and effect relationships that govern how reality works is essential for success. Be radically open-minded and listen to believable people with good track records.

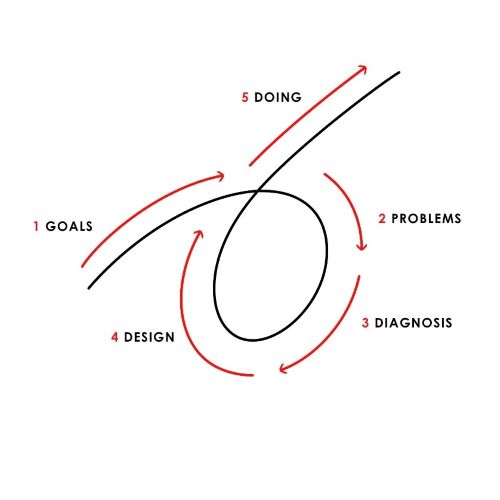

- Get what you want out of life by following the 5-step process (goals, problems, diagnosis, design, and doing).

Work Principles

- The best approach to decision-making is an idea meritocracy where the best ideas win out. This requires people to put their honest thoughts on the table, have thoughtful disagreements about them, and use idea-meritocratic ways (like believability-weighted voting) to get past any remaining disagreements.

- To be successful, you need to be like a conductor of people:

- Get the right people—bad hires are extremely costly and most people don’t change all that much.

- Accurately assess them—tools and objective data can help with this.

- Assign tasks and responsibilities well—assign based on people’s abilities (rather than job title), set clear expectations, and hold people personally responsible.

- Pay attention to the bigger “machine” that makes up your organisation:

- Make sure it is focused on goals that you are excited about.

- Understand that the machine operates at different levels—find ways to leverage the people at the top.

- Don’t forget governance—power should be checked and balanced, so that the interests of the whole are placed above those of any individual.

Detailed Summary of Principles: Life and Work

Ray Dalio is the founder of Bridgewater Associates, one of the largest hedge funds in the world, and a multi-billionaire.

Part I of the book covers Dalio’s life from 1949 to 2017. He goes over how he made various mistakes, which gave him the humility to learn and improve. While it’s interesting to read some of Dalio’s observations about historic events, there’s not enough to learn much about finance or decision-making here.

This summary therefore focuses on Parts II (Life Principles) and III (Work Principles). There is, unsurprisingly, some overlap between these two sections. My summary will also be more of a sampling of the points I found interesting, because Dalio lists way too many principles to summarise in full.

Why Principles?

Being principled means acting consistently with principles that you can clearly explain.

Principles allow you to systemise your decision-making criteria and convert them into algorithms for computers to carry out. One advantage of doing this is that computers are immune to biases and herd mentality, so will never panic. Computers can also observe patterns and come up with their own pattern-matching algorithms without understanding any of the logic behind them. However, Dalio personally prefers making decisions based on an understanding of cause-and-effect relationships to relying on algorithms he doesn’t understand (but he’s not sure this is an entirely logical preference).

When Bridgewater was small, its principles were mostly implicit. But as the firm grew, Dalio felt the need to make their principles explicit and explain the logic behind them. He first prepared a rough list of about 60 Work Principles in 2006.

Most people can’t explain the principles they apply. It’s very rare for people to write their principles down at all. The advantage of writing out your principles is that it lets you debate them with other people, and reflect on and refine them.

Life Principles

Understand how reality works

Understanding how reality works is essential for success. When you understand the cause and effect relationships that govern reality and have principles for dealing with it, you can achieve your goals. Conversely, idealists with dreams not grounded in reality will flounder.

Understanding your own weaknesses will make you freer and will let you deal with them better. If you know where you are weak, you know where you should defer to others. However, accepting your weak parts can be hard because we all have deep-seated needs and fears (of being loved, of not surviving, etc) in the primitive parts of our brains. These can act as defence mechanisms against reality.

Color-blind people eventually find out that they are color-blind, whereas most people never see or understand the ways in which their ways of thinking make them blind.

The fundamentals of effective decision making are relatively simple and timeless. Logic, reason, and common sense are your best tools for understanding reality and working out what to do. But intuition can be useful too. Animals in the wild instinctively make expected value calculations to optimise the energy they expend to find food, because the ones that did this well thrived and passed on their genes.

None of us are born knowing what is true. We have to figure it out as we go. Be radically open-minded and replace your attachment to “being right” with the joy of learning what’s true. Open-minded people genuinely believe they could be wrong and are more interested in listening than speaking.

One of the most important decisions you can make is who you listen to. Listen to believable people—those who are well-informed and have a good track record on the issue in question. Some people may be believable on one issue but not on another. Listening to others can lead you to much better answers than you could come up with on your own.

Other observations

- Understand the difference between first, second and third-order consequences. Root causes of problems can manifest themselves over and over again in seemingly different situations.

- Absolute levels matter. People might say “it’s getting better” without considering how far below the bar “it” is or whether the rate of change suggests it will get above the bar in an acceptable amount of time.

- Nature is self-correcting, but it optimises for the whole rather for any individual. Everything—including people, companies and countries—has to evolve or die.

- Most attributes are double-edged. They can help us or hurt us depending on the situation. The more extreme the attribute, the more extreme the potential good or bad outcomes.

Get what you want out of life

Getting what you want out of life involves the following 5-step process:

- Have clear goals.

- Identify and don’t tolerate the problems that stand in the way of your achieving those goals.

- Accurately diagnose the problems to get at their root causes.

- Design plans that will get you around them.

- Do what’s necessary to push these designs through to results.

The key is doing all 5 steps well and in order.

This summary just focuses on the Goals step. The keys here are to:

- Prioritise. You can have virtually anything you want, but not everything. The amount of time and energy you have are fixed, so make sure you figure out what you want and invest time and energy in the goals that will yield the biggest returns.

- Be ambitious. Set goals beyond what you know you can achieve, else your bar is way too low. Don’t rule out goals you think are unattainable. If you’re not failing, you’re not pushing your limits. If you’re not pushing your limits, you’re not maximising your potential.

There are many paths to happiness. Even the worst circumstances can usually be made better with the right approach. One of Dalio’s friends became a quadriplegic after a diving accident but still found happiness because of the way he approached his situation.

The marginal benefits of having more money and wealth fall off pretty quickly. At some point, the burdens that come with having more may not be worth the marginal benefits. Beyond a basic level, there is no correlation between happiness and conventional markers of success. [More recent research suggests otherwise. Though I’m sure Dalio is right that there are plenty of wealthy but unhappy people, as wealth cannot guarantee happiness.]

Do what you love—this can be any kind of long-term challenge that leads to personal improvement. This doesn’t have to be a job, though Dalio believes it generally is better if it is.

Make good decisions

Decision-making is a two-step process: learning and deciding. The biggest threat to good decision-making is harmful emotions.

Good habits lead to good decisions. Everyday decisions typically involve subconscious processes that are complex and not widely understood. Habits put your brain on autopilot so you can do stuff without thinking about them.

The greatest plan is worthless if you don’t execute. Having the best life possible consists of knowing what the best decisions are and having the courage to make them.

Work Principles

Work Principles are probably even more important than Life Principles, since a group’s power is much greater than an individual’s.

I’ve divided this section into 3 broad parts:

- Idea meritocracy

- People

- The Machine

Idea meritocracy

An idea meritocracy is an environment where the best ideas win out. It is evidence-based, and doesn’t just follow the decisions of the CEO or whoever has power.

Dalio thinks this is the best approach to decision-making, and superior to the traditional autocratic or democratic approaches in almost all cases. While an idea meritocracy isn’t for everyone, he estimates around two-thirds of people who try it take to it.

An idea meritocracy must operate according to agreed-upon principles. The three things required for an idea meritocracy are:

- People put their honest thoughts out on the table.

- Thoughtful disagreements in which people evolve their thinking to come up with the best possible collective answers.

- Using idea-meritocratic ways of getting past remaining disagreements—the main one Dalio discusses is believability-weighted decision making.

When this works, an idea meritocracy is both liberating and effective. However, Dalio admits that even in an idea meritocracy, merit cannot be the only determining factor—you also need to take into account vested interests, like the owners of a company.

Honest thoughts

Dalio is a big proponent of radical transparency. People must be aligned on many things in order for an organisation to be successful. When everyone is held to the same principles and decision-making is transparent, it’s hard for people to pursue their own interests at the expense of the organisation’s.

Radical transparency doesn’t mean full transparency, as some things need to be kept confidential for legal or commercial reasons. But Bridgewater is more transparent than most organisations. For example, almost all meetings are recorded, so that people can reflect on and learn from them without being in the room.

You should distinguish between complaints and suggestions or questions. These are different things and should be treated differently. The key is helpfulness. When people can question, debate, challenge and probe ideas and proposals (including the Principles themselves), it leads to better quality. But private complaints and grumblings aren’t helpful. Moreover, after the decision-making machine has settled an issue and moved on, it is unhelpful to keep stubbornly insisting that you were right.

Thoughtful disagreements

Disagreements are inevitable. Avoiding a conflict means you won’t resolve the underlying differences. People who suppress minor conflicts tend to have much bigger conflicts later on.

When faced with a conflict, start by assuming you’re not communicating or listening well instead of blaming the other party. Remain calm and analytical. If either party is too emotional to be logical, defer the conversation.

Resolving a disagreement requires a balance being open-minded and assertive:

- Open-minded means seeing things through the other’s eyes. Repeat what you’re hearing to make sure you’re getting it right.

- Assertive means clearly communicating how things look through your eyes.

The right balance between the two depend on your relative understanding of the subject. If you’re more believable on it, you should be more assertive, playing the role of a teacher—explaining things and answering questions. If you’re less believable, you should be more open-minded, like a student asking questions.

Dispute Resolver

One of the tools used in Bridgewater is the Dispute Resolver, which uses a series of questions to guide people through a disagreement using idea-meritocratic principles. Among other things, the Dispute Resolver can identify believable people on the issue who can help determine if the dispute is worth escalating.

Focus on what’s accurate rather than how it’s perceived. People who receive critical feedback often get preoccupied with its implications rather than whether it’s true. This is a mistake. If you focus on what’s accurate, you’ll focus on the most important things.

Work hard to solve disagreements, especially with believable people. If the issue is important, Dalio recommends slowly working through the disagreement until you’re on the same page, rather than just going along with the other person’s thinking even when it doesn’t quite make sense to you. When worked through properly, disagreements lead to better decisions and new insight.

Getting past remaining disagreements

Don’t get stuck in disagreement—escalate or vote. It’s more important that the decision-making process is fair than that you get your way on a particular issue. At Bridgewater, the process for escalating disputes is not unlike what you’d find in courts (but less formal).

Group decisions in Bridgewater are based on believability-weighted votes. Dalio thinks that this is the fairest and most effective decision-making system when done correctly and consistently, and even people who disagree with the decision can usually get behind a decision if they accept the believability-weighting process. Sometimes a single “Responsible Party” can override a believability-weighted vote, but they’ll do this at their own peril especially if the believability-weighted vote had a clear margin.

Dot Collector

Bridgewater uses an app called the Dot Collector in meetings to solicit people’s views in real-time. The app’s name comes from the fact that participants continuously record their assessments of each other by giving them positive or negative “dots”. The Dot Collector includes a polling interface which allows for believability-weighted and normal-weighted voting, so people can see the difference between the two.

People

Meaningful relationships and meaningful work are mutually reinforcing.

Meaningful relationships are invaluable for building and sustaining a culture of excellence. Ideally, you want to work with “partners” whose values and interests are aligned with yours. However, meaningful relationships can be hard to maintain as an organisation grows—beyond about 100 people, Bridgewater’s sense of community faded.

To be successful, you need to be like a conductor of people. The main advantage of working in groups is that it’s much easier to obtain all the qualities you need for success in a group than in a single person. No one can play every instrument yet, together, the team excel.

Getting the right people

Hiring is important, because bad hires are extremely costly. You can waste months or years along with countless dollars in training and retraining. There are also intangible costs like lower morale or gradual drop in standards. So if you’re less than excited to hire someone for a particular job, don’t.

People are wired very differently and typically don’t change all that much, especially in short periods like a year or two. Many of our mental differences are physiological, but are much less obvious than differences in how our bodies work. If you know what someone (including you) is like will tell you what you can expect from them. Dalio is a big fan of personality tests like Myer-Briggs Type Indicator to work out what people are like.

When hiring, match the person to the design. First, understand the responsibilities of the role and the qualities and skills needed to fulfill them. Then look at whether the person possesses those qualities and skills. Note that performance in school doesn’t tell you much about whether a person has the values and abilities you want.

But you also want to hire for the long term. Don’t just hire people for the first job they will do; hire people you want to share your life with. You want people with whom you are compatible, but who also challenge you. These people should have great character, in that they are radically truthful and committed to the organisation’s mission. Most people will operate in a way that maximises the amount of money they get and minimises the amount of work they do to get it. When you find honourable people who treat you well even when you’re not looking, make sure to treasure them.

If it comes to it, you must be willing to “shoot the people you love”, instead of lowering your standards. Most people naively assume that when someone does something wrong, they will learn from their mistakes and change. Dalio thinks it’s best to assume people won’t change unless you have good evidence to suggest otherwise.

Assessing people

You need to know your people extremely well, provide and receive regular feedback, and have quality discussions. Tools, protocols and evidence can help with this.

Make sure your assessments of people are accurate and that the other person agrees. Your reports shouldn’t see you as their enemy but as someone trying to help them.

One way to ensure accurate assessments is to collect objective data on people. Effective metrics can tell you what and who is doing well or poorly, all the way down to specific people. You can also tie your metrics to an algorithm with consequences (e.g. bonuses for delivering certain outcomes).

To get good metrics, think first about what information you need to answer your pressing questions, then figure out how to get it. You don’t need to watch what everyone is doing all the time to make sure they do a good job—just know what the person is like and get a reasonable sample.

Baseball Cards

One tool Bridgewater uses to manage people are Baseball Cards, which summarise an employees’ key attributes, such as their strengths, weaknesses and what they’re generally like.

The attributes are collected through tests, reviews, and records of their choices over time, and the person being assessed has a chance to weigh in with their own perceptions. These cards also help match people to roles within the company.

Make sure the information that goes into your metrics is accurate. Manager ratings, for example, can be highly subjective as some are easier or harder graders. Forced rankings (i.e. grading on a curve) can be help reduce subjectivity. Dalio admits that Bridgewater’s evidence-based approach to learning about and sorting people is imperfect. However, he still thinks it’s much fairer and more effective than the subjective systems most organisations use.

People will evolve and learn. Sometimes you’ll have to let people make mistakes as it’s better to teach people to fish than to give them fish. But the evolutionary process should be relatively quick—Dalio thinks it takes between 6-12 months to get to know a new employee reasonably well, and about 18 months for them to internalise and adapt to the culture. So it’s more of a discovery process, as people don’t change all that much.

Assigning tasks and responsibilities

When you assign responsibilities and authority, assign them based on workflow design and your assessment of people’s abilities, rather than job titles. Don’t, for example, give HR the responsibility of determining who to hire or fire. Also make sure people understand the difference between goals and tasks—otherwise you can’t trust them responsibilities.

Be clear on expectations and what the quid pro quo is. Allow time for rest and rejuvenation, and celebrate victories. When you’re being generous, make sure it’s recognised as such, and doesn’t become an expectation.

If you put your goals in the hands of capable ‘Responsible Parties’ and make it clear that they are personally responsible for achieving those goals, they should produce excellent results. Capture assigned tasks on a checklist so that both parties know what’s been done and what still needs doing. That said, people’s responsibilities are more than just what’s on their checklists and they should do their whole job well.

Make reporting lines and delineation of responsibilities very clear. Dual reporting causes confusion and muddies accountability, especially when the supervisors are in two different departments.

The Machine

An organisation is like a machine with two major parts: culture and people. Get both right, and your organisation will be great.

Beware of paying too much attention to what is coming at you and not enough attention to your machine.

Goals

Your goals should be ones you and your organisation are excited about. If you’re not excited about a goal you’re working for, drop it.

Think about how your tasks connect to your goals. Don’t act before thinking—the time you spend thinking through a plan will be virtually nothing compared to the amount of time spent executing it, and a good plan makes the execution far more effective.

Different levels

The machine operates at different levels. Decisions must be made at the appropriate level, and should be consistent across levels. When you encounter cross-departmental issues, involve the person at the point of the pyramid.

The most important Responsible Parties are those responsible for the goals, outcomes, and machines at the highest levels. You don’t need to make judgments about everything—”by-and-large” is the level at which you need to understand most things to make an effective decision. But you do need to know your people extremely well.

Find ways to produce leverage, so that the people at the highest levels can achieve more with less. For example, Dalio estimates he worked at about 50:1 leverage at Bridgewater, meaning that for every 50 hours someone worked for him, he’d spend around 1 hour with them. The ratios for those beneath Dalio would typically had ratios of around 10:1 or 20:1 with their direct reports. Principles are one form of leverage, but merely writing down or talking about the principles is not enough. Behavioural change only occurs when people practise them.

You can facilitate this by embedding your principles in tools, as technology is another form of leverage. Good tools help you collect data and convert it into decisions. Bridgewater uses a variety of tools to support its idea meritocracy. One example is the Coach app (see My quick review of the Principles in Action App), which helps people handle common situations like disagreements or some unethical action by referring to the principles relevant to similar past instances.

Daily Update Tool

For years, Dalio has asked each of his direct reports to take 10-15 mins to write up a brief email of what they did that day and the issues they’re currently facing.

Later, he used a Daily Update Tool to help him better manage these daily updates. The tool pulls his reports’ updates into a dashboard with metrics, which makes them easier to track.

Problems and mistakes

Problems are inevitable. To create a culture of excellence, you must constantly reinforce the need to identify problems, no matter how small. Explicitly ask for regular, honest feedback and give people ample opportunity to speak up. But note that complaints can sometimes come from people who only see one side of the decision and don’t know what factors the decision-maker had to weigh.

Accurately diagnosing a problem is key to both progress and quality relationships. Some problems are just one-off imperfections, while others are signs of a root cause that will show up repeatedly if not fixed. To work out which is which, you must attribute specific actions or omissions to specific people. Next, work out if a specific person’s failure is due to lack of capacity, training or abilities. Sample size is important—has the person made similar mistakes in different circumstances? Problems of capacity are relatively easy to fix. Problems due to inadequate training are a bit harder. But problems caused by a lack of ability may not be fixable at all.

Don’t get frustrated. If something seems hard or frustrating, step back and triangulate with others to see if there’s a better way to handle it. Figure out what to do about it instead of just wishing it were different.

Governance

Governance is the oversight system that checks and balances power. Since power will rule, it must be placed in the hands of the right people, who will check and balance others’ power. The “right people” must have both the ability and the courage to hold others accountable. Most people don’t.

Good governance ensures that the interests of the whole are placed above the interests and power of any individual or faction. In an idea-meritocracy, a single CEO is not as good as a great group of leaders. Bridgewater, for example, has multiple CEOs and Chief Investment Officers. So beware of fiefdoms—you can’t allow loyalty to a leader to conflict with loyalty to the organisation as a whole. Even the most benevolent leaders are prone to autocracy, because managing a lot of people with very little time means they have to make many difficult decisions quickly. It’s therefore easy for leaders to lose patience with arguments and issues commands instead. But no single person should be irreplaceable or more powerful than the system.

Reporting lines and decision rights should also be clear. The board and the CEO should have independent reporting lines (though there should be cooperation between them). People should also know how much weight each person’s vote has so they know what the decision will be if a disagreement isn’t resolved.

Good controls and guardrails can protect you from the dishonesty of others. Use “public hangings” to deter bad behaviour. But recognise that even the best governance system with principles, rules and checks and balances cannot substitute for a great partnership.

My Review of Principles: Life and Work

This book made it onto my reading list because of Dalio’s excellent YouTube video, How the Economic Machine Works, which I’ve watched multiple times over the years. But, sadly, I found it rather disappointing.

It’s not a terrible book. There actually looks to be a great deal of wisdom in it, and it was interesting to read about Bridgewater’s unusual culture and Dalio’s unorthodox approaches to management.

It’s just terribly written. There are plenty of clunky, multi-part sentences that squish a bunch of different ideas together. The ideas themselves are repeated frequently and scattered throughout the book. There’s a structure to the book, but Dalio doesn’t stick closely to it. The density of useful ideas is high, but Dalio only ever skims across the surface.

I suspect the reason Principles is so badly written is because Dalio originally wrote it as a PDF for internal consumption at Bridgewater. Unfortunately, it reads like a book still in draft. Interestingly, Dalio released a “Principles in Action” mobile app (Apple, Google), which I would recommend over the book. (The app is free and even lets you read Principles for free on it.)

I see the main value of Principles as an example of how you might externalise your core beliefs and principles. It’s something I’ve been interested in for a while, and I even started an outline of my core beliefs earlier this year. My reasons for doing this are not to try and leverage my own abilities but to clarify my own thinking, identify logical inconsistencies, and guard against motivated reasoning. So although I agreed with some of Dalio’s principles, disagreed with others, that’s all beside the point

As Dalio explains:

So, as I believe that adopting pre-packaged principles without much thought is risky, I am asking you to join me in thoughtfully discussing the principles that guide how we act. When considering each principle, please ask yourself, “Is it true?” While this particular document will always express just what I believe, other people will certainly have their own principles, and possibly even their own principles documents … . At most, this will remain as one reference of principles for people to consider when they are deciding what’s important and how to behave.

On a final note—I know Dalio has his detractors, such as Rob Copeland who wrote The Fund: Ray Dalio, Bridgewater Associates, and the Unraveling of a Wall Street Legend. I haven’t read that book (and don’t plan to) but apparently it paints Dalio as an “egomaniacal cult-of-personality leader”. I don’t know if it’s true, but I could believe it. Dalio is surprisingly blunt in Principles and I saw a few signs that raised eyebrows (“public hangings” or “even the most benevolent leaders are prone to autocracy”).

Luckily, I think you can get value from Principles regardless of your view of the man behind them. Even if Dalio implemented his own ideas poorly—there are claims that he manipulated the believability-weighting system so that his opinion always mattered most—it doesn’t mean the system itself is flawed. And even if certain ideas worked at Bridgewater, they may not work for you—I suspect believability-weighting will be much harder to pull off in industries where feedback isn’t as frequent or clear as it is in finance. Books like these are really just sources of ideas—you just have to try the ones that seem to be worth trying and moderate your expectations.

Let me know what you think of my summary of Principles: Life and Work in the comments below!

Buy Principles: Life and Work at: Amazon <– This is an affiliate link, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through it. Thanks for supporting the site! 🙂

If you enjoyed this summary of Principles: Life and Work, you may also like:

- My quick review of the “Principles in Action” app

- Book Summary: Thinking in Systems by Donella Meadows — Dalio talks a lot about cause and effect and understanding the broader “machine”. Though Thinking in Systems is not a business book, it gives much better explanations of how machines/systems actually work.

- Book Summary: Good Strategy, Bad Strategy by Richard Rumelt

7 thoughts on “Book Summary: Principles: Life and Work by Ray Dalio”

I had that on my long list of books to read but now I won’t :).

Your review fits with my impression, and I was aware of the various criticisms. Seems like he’s got some interesting ideas, but I don’t want to wade through a hard-to-read book.

Cool, glad I saved you some time!

I have seen a few other much more positive reviews (like this one) from people who seem generally sensible. But I think they read the book at a time when its ideas really were new and applicable to them – and I don’t think that’s the case for you or me.

Reading about the cultural values/practices he emphasizes makes me wonder… how well do we think these are actually implemented and enforced? Especially with something like radical transparency. And maybe this can connect to a broader point about how important company “cultural values” actually are.

Yeah, I have no idea how well things like radical transparency are enforced. I can believe Bridgewater was more transparent than most, especially at the beginning. It does seem hard to maintain as a company grows – but he also talks a lot about the importance of hiring the right people to begin with.

On your broader point about company/organisation values – having worked in different places with vastly different cultural values, I don’t think they’re overrated. Cultural values can make a huge difference to your day-to-day work experience and I’m sure the overall performance of the organisation. But firms also really enjoy talking about their values in waffley, meaningless ways that just make them sound good and which do not reflect the firm’s true values.

Oh yes, I like how you frame that differentiation on company values. TRUE values matter a lot, but how much they reflect corporate-espoused “values” is another question.

FWIW in my limited experience, working at Amazon, it did seem to make **some** difference (people would occasionally refer a specific cultural tenet when justifying their actions) but I’m sure it varies wildly from org to org

What are your favourite sites that summarise books?

I mostly use Blinkist. Their summaries are not the best, but enough to give me an idea of what a book is about to help me decide if it’s worth reading.

I also follow some sites like AstralCodexTen that occasionally do book reviews, not summaries.