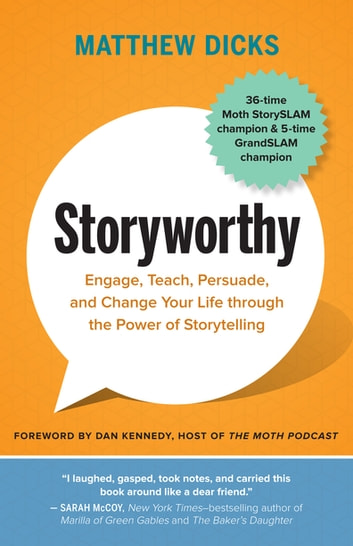

This book summary of Storyworthy by Matthew Dicks explains how to find your story, craft it, and tell it to others.

Buy Storyworthy at: Amazon | Kobo (affiliate links)

Key Takeaways from Storyworthy

Finding your story

- Every story has a five-second moment at its heart. These are moments about growth, change, or some realisation.

- Big, exciting stories are actually harder to tell, because they are less relatable. To tell a big story, you still have to find the five-second moment in it.

- One of the best ways to find stories is by doing “Homework for Life” — spending just five minutes a day jotting down your most storyworthy moment from that day.

- Not only will Homework for Life give you plenty more stories, it will also make you recognise and appreciate the small, meaningful moments that make up our lives.

Crafting your story

- Your story should start at the opposite of the five-second moment so that your story has an arc.

- Stories must have stakes. One way to build stakes is by describing your plan, bringing your audience with you.

- Some lies are okay — omission, compression, simplification, reordering. Lies should be for the benefit of the audience, to make things easier to follow, etc. Making up things that didn’t happen, or lying to make yourself look better, are not okay.

- Immerse your audience. Give each scene a location, so your audience can see it in their minds. Use the present tense. And don’t pop the bubble by doing things like referring to your story as a story.

- Stories are about change and contrasts. Use “but” and “therefore”, rather than “and” to join sentences and scenes.

- Keep things short and simple, particularly when your story is oral. Aim for 5-6 minutes.

- Surprise is the only way to make your audience feel an emotion. To generate surprise, you might bury the lead in other details

- Humour is helpful but not essential. It should be used strategically. For example, a laugh at the start can settle and reassure your audience.

- If you tell a story about your success, you should cast yourself as an underdog or downplay your success.

- Endings should be a little messy. They should linger with the audience, so that they return to it in their heads even days afterwards — like a coat that is difficult to take off.

Telling or performing your story

- Don’t rehearse in front of a mirror, as you’ll never see yourself when performing.

- Don’t memorise your story. Just remember the first and last lines, and each “scene”. That comes off more authentic and will help you recover even if you forget a line.

- Find one friendly-looking person to each of your left, right and middle and make eye contact with them throughout.

- Always use a mic if offered one, and take the time to check it is set up properly. Even if you have a mic, you still need to project your voice.

Detailed Summary of Storyworthy

To get a sense of Dicks’ storytelling skills and style, watch him perform these stories featured in the book:

I will refer to some of these stories as examples throughout the summary (as Dicks did in the book), so watch those videos first if you don’t want to be “spoiled”. (Don’t worry, they’re short.)

What is the point of the book?

Storyworthy tries to help you tell better stories.

Everyone can benefit from getting better at telling stories, even if they have no intention of performing in a public show. Telling stories better can improve your presentation skills and sales pitches.

No one ever made a decision because of a number. They need a story.

Telling good stories can also make you more interesting on dates and social situations. It can even help grandparents connect with their grandchildren. One of Dicks’ primary goals is to get people to share better stories and conversations about their lives, so that the world will become a more entertaining and meaningful place.

Dicks admits that not all storytellers agree with his strategies. Storytelling is more art than science, and there are no universal laws or absolutes. But he claims that every student who has followed his advice has become an effective storyteller.

Finding your story

What is a story?

Storyworthy is about personal stories about yourself, rather than fiction or folktales. Personal stories spark a connection and bring people closer together.

A personal story has three requirements:

- Change. It can be a tiny change, and it need not be a positive change. But stories without change won’t leave a mark on anyone. They are just anecdotes, drinking stories or vacation stories. Although such stories can be fun, they are ultimately forgettable.

- It must be your story. People want to hear your story because it requires courage and vulnerability to tell. They would rather hear a story about you than about your friend, even if your friend’s story is better. You can still tell stories about someone else, but you have to make it about yourself—how that person’s actions or circumstances impacted you.

- It must pass the “dinner test“. The story you tell in public shouldn’t be too different from the kind of story you tell at the dinner table. Don’t use weird hand gestures, unnatural sounding phrases, sound effects, or unattributed dialogue.

Storyworthy moments are everywhere

People often think that big, unusual events make the best stories. Dicks disagrees. He argues it’s the simple stories about small, relatable moments in our lives that are most compelling. My Childhood Secret is one of Dicks’ most-requested stories. Most of us are just bad at identifying them and recognising their importance.

Dicks suggests three tools to help you find storyworthy moments:

- Homework for Life — discussed below.

- Crash and Burn — continuous, stream of consciousness writing.

- First Last Best Worst — thinking of the first, last, best and worst experiences you’ve had for various prompts (e.g. kiss, gift, car). This can also act as a game or icebreaker.

[I only describe Homework for Life in any detail as I think it’s the most original and important of these three method. Even if you have zero intention of ever performing your stories, I can see a lot of value in Homework for Life, but I can’t say the same for the other two methods.]

Homework for Life

Every day, you ask yourself what story you would tell if you had to tell a story onstage about something from that day—no matter how boring and inconsequential that day may seem. Reflect for a few minutes, then write down a sentence or two to help you remember it.

Dicks uses an Excel spreadsheet with one column for the date and one column for the snippet, but you can use whatever works for you. The key is to keep it short so that it’s easy to do, and you can keep up the habit. It shouldn’t take more than 5 minutes a day.

After six years of doing Homework for Life (at the time of writing), Dicks has more than 500 possible story ideas on his spreadsheet. Not every day will yield a story idea. Some days you might just get an amusing anecdote, or even nothing. This is particularly common for the first few months, up to a year.

But, over time, Homework for Life helps you develop a storytelling ‘lens’ and you get better at identifying storyworthy moments as you’re living them. This helps you recognise the beauty and meaning in the small moments of your life. Homework for Life can also help you see patterns in your actions that you might not otherwise notice. Reflecting regularly can trigger old memories that you might otherwise forget. It can also make you more willing to try new things. There are therefore many advantages to this daily exercise.

Crafting your story

Stories don’t start out polished and perfect. They have to be crafted. Dicks runs storytelling workshops where he lets students pick a random untold story idea from his Homework for Life spreadsheet, and he’ll attempt to craft a story from it out loud in real time.

It’s easy to listen to a well-crafted story from a professional storyteller and assume that these things spring forth from our brains like tulips in the spring. I wish. It’s a messy process. Ugly and halting and imperfect. Knowing this makes my students feel better about their own messy process.

The five-second moment

All great stories, no matter how long, tell the story of a five-second moment in a person’s life when something changes forever. Falling in love. Falling out of love. Changing your mind. A realisation. These are the moments you look for when doing Homework for Life. Jurassic Park, for example, is not a story about dinosaurs. It’s about a man who changes his feelings about children.

“Big” stories can be the hardest to tell. In This is Going to Suck, Dicks dies on the side of the road, which is not a common or relatable experience. So he doesn’t make that the focus of the story and the audience will almost forget it by the end.

Your story can only be about one five-second moment. Even if your story actually means multiple things to you, choose one meaning to focus on when telling it. That will affect how you craft your story — where you begin it, what you omit, what you emphasise, etc. You can tell a different version of it when you tell it for another meaning.

Storyworthy contains lots of advice on crafting your story. However, the first step is just to tell your story out loud without worrying about all that advice to try to find the meaning of that story and your five-second moment. Sometimes you’ll see the meaning immediately, but other times you need to tell it to understand it.

Finding your beginning

The beginning of your story is very important. Don’t just use the first thing that comes to mind. Dicks says more than half the time he spends crafting stories is spent searching for the beginning.

Your five-second moment helps you find both the beginning and the end to your story. The end is simply the five-second moment itself. The beginning will usually be the opposite of that moment to create an arc in your story. Stories always involve change. It may just be incremental change, and it may not be a positive change, but it still must be change.

The story of how you’re an amazing person who did an amazing thing and ended up in an amazing place is not a story. It’s a recipe for a douchebag.

The story of how you’re a pathetic person who did a pathetic thing and remained pathetic is also not a story. It’s a recipe for a sad sack.

Some tips for finding your beginning:

- Start as close to the end as possible. A simple story that takes place in a limited time and space is easier for an audience to follow, and easier for you to remember and tell. Often, Dicks will pick one place to start his story, and then work closer and closer to the end as he revises it.

- Use forward momentum if possible. For example, start your story when something is already happening. This can create instant momentum and immerse your audience in a story. Movies do this a lot.

- Don’t start off by setting expectations. For example, saying “This is hilarious,” or “You’re not going to believe this”. It can set unrealistic expectations and makes it less likely that you’ll be able to surprise your audience. It’s also boring.

Stakes

Every story must have stakes. Stakes are why audiences listen and care about your story. A story without stakes, or with low stakes, is boring. Some stories naturally come with stakes, but others don’t, so you’ll have to find ways to create or raise stakes.

Five strategies Dicks uses to raise the stakes in a story are:

- The Elephant. The Elephant clearly signals where the story is going. Every story needs an Elephant, which should appear as early as possible, so that your audience has a reason to listen. Elephants can “change colour” — your audience may think they are on one path, and then you surprise them by showing them they’ve been on a different path. This can be a very effective strategy, particularly if the end of your story is sad or emotional. You don’t want the whole story to be heavy, so you might make the beginning light and funny. Two examples of this are in The Promise and Lemonade Stand.

- Backpacks. Backpacks load up the audience with your hopes and fears to make them feel the same worry, anticipation and suspense you did at the time. For example, heist movies like the Ocean’s Eleven franchise always spend a lot of time explaining the robbers’ plan so you feel invested in it. Backpacks are particularly effective when a plan does not work. It’s odd. The audience wants storytellers to succeed, but they don’t really (or at least they don’t want everything to go smoothly).

- Breadcrumbs. Give your audience hints to keep them guessing. Find a balance between giving enough hints to pique your audience’s curiosity but not so much as to allow them to guess correctly. Breadcrumbs are particularly effective when the thing that happens is unexpected, so your audience is likely to guess wrongly.

- Hourglasses. Slow things down at the key moment. When you reach the key moment your audience has been waiting for, you want to milk the moment for all it’s worth. You can do this is by describing irrelevant details or summarising what’s already happened. Slowing your pace and lowering your voice can also draw out the suspense.

- Crystal Balls. Crystal balls are false predictions that make your audience wonder if your prediction will turn out correct. We make predictions all the time, many of which turn out to be false. By sharing what you were predicting at the time, your audience will be more likely to follow along with you. Your false prediction should be something that seems reasonably possible. It should also be interesting or exciting if true.

Dicks uses all 5 strategies in Charity Thief (which is why he uses this story as a model when teaching). While the ending of Charity thief is quite compelling, the beginning is not, so it needs extra work. But these 5 techniques will only get you so far. A story without stakes will always be boring.

Lies

Some lying or truth-bending is inevitable as stories will never be 100% accurate.

Three important caveats!

- Only lie for the benefit of the audience, and never for personal gain (i.e. don’t lie to make yourself look better).

- Memory is unreliable. Research shows that every time you tell a story, it becomes less true. Stories will inevitably contain mistakes or inaccuracies. But try to be strategic in your accuracies.

- Don’t make things up. Don’t add something to a story that was not already there.

There are 5 permissible lies in storytelling:

- Omission. Omissions are inevitable. Everything in your story should serve your five-second moment, so cut or downplay things that don’t emphasise that moment. People are frequently omitted from stories if they’re irrelevant to it. Even if something is hilarious or entertaining, it may still be better to omit it if it detracts from your five-second moment.

- Compression. In real life, stories might take place over several days at different locations. But those details may be ultimately irrelevant to your story and five-second moment, and add unnecessary complexity and distraction. Especially when you’re telling an oral story, you want your audience to follow along easily. If your audience has to take the time to construct a mental map or timeline, you’ll lose them. Compression makes a story easier to tell and to follow, and can also increase the drama.

- Assumption. Assumption is when you fill in a missing detail that you can’t remember, but which is critical to the story. Your assumption has to be reasonable. For example, in one of Dicks’ stories, he wants the audience to picture in their minds a Batman toy hitting a car. He can’t remember the make or model of the car, so he assumes that the car was a station wagon (which were common at the time).

- Progression (changing the order). Progression can make a story more emotionally satisfying or easier to comprehend. For example, in one story, Dicks suggests reversing the order of events because “it’s always better to make people laugh before they cry.” Dicks thinks this is the least common of the five lies. [I also think this is the most dishonest of the five lies, at least when done to make things more emotionally satisfying. Perhaps others do too, which may explain why it’s the least common.]

- Conflation. In real life, change and personal growth usually occurs gradually, rather than in a “Eureka!” moment. Conflation pushes together change and emotion into a single moment, making your story shorter and easier to follow. [This seems similar to compression, but focused on internal emotions and thoughts, rather than external events.]

Immerse your audience

Provide a location

Dicks argues that every storyteller’s goal should be to create a “cinematic experience in the minds of every listener”. To do this, you need to provide a physical location for every moment of your story so that your audience can “see” it in their heads. A single sentence providing a location can convert an essay into a story.

At times, you will need to give some backstory. Dicks demonstrates how he does this in Charity Thief by talking about how he’s parked at a gas station, gripping his car’s steering wheel, thinking about his life circumstances. He just lets his 20-year-old self explain his backstory, instead of his present-day self. This way, the audience never has to leave the setting of the story.

Use the present tense

The present tense creates a sense of immediacy and can make an audience feel like they are right there with you in the story. It also helps you “see” your story as you relive the moment, which can help you connect to it.

You may alternate between the present and the past tense. The past tense may be particularly useful for:

- Telling backstory. However, this is not a rule. For example, when Dicks talks about his friends’ old-fashioned phone tree in This Is Going to Suck, he uses the present tense because it’s a powerful moment and he wants you to “see” the phone tree happening in real time.

- Creating distance. Sometimes you want to create a bit of distance and you don’t want your audience right there with you. Dicks gives the example of a story about his son peeing — he doesn’t want the audience right there in the bathroom!

With practice, shifting between the past and present tense will become instinctual. It’s barely noticeable when you listen to a story, but becomes more obvious a story is written down.

Although Dicks is a big proponent of the present tense, he understands that some people never really get the hang of it. They find the past tense much more natural and trying to use present tense is more effort than it’s worth. That’s okay, as great stories can be told in the past tense, too. But you should at least give the present tense a try.

Don’t pop the bubble

Creating a cinematic experience also means not doing things that take the audience out of the story, such as:

- calling your story a “story”;

- making thesis statements;

- asking rhetorical questions;

- cracking jokes or making observational non-sequiturs (the focus should be on the story, not on yourself);

- acknowledging the audience’s existence (e.g. saying “you guys”);

- wearing distracting clothing;

- using celebrity or pop culture references (a good portion of your audience won’t get it, and those that do will start picturing that celebrity in your story instead of the actual person — which can be jarring); and

- using anachronisms (sometimes these are unavoidable, but try not to use them).

Use Contrast — “But” and “Therefore”

It’s boring to connect sentences and paragraphs with the word “and”. There’s no momentum or contrast. Dicks recommends using the words “but” and “therefore” instead. (You can also use their synonyms, as well as implicit buts and therefores). These words make a story feel like it’s going somewhere, changing direction.

Thinking about the next “but” or “therefore” can help you craft your story by figuring out where your story is headed next. Even the creators and writers of South Park (Trey Parker and Matt Stone) use this when storyboarding their scenes.

Stories are not a simple recounting of events. They are not a thorough reporting of moments over a given period of time. Stories are the crafted representation of events that are related in such a way to demonstrate change over time in the life of the teller.

Negative statements are also useful in storytelling. “I’m not smart” is better than “I am dumb”, because it suggests the potential to be smart. But this isn’t always true. Simple, positive statements can be better at summarising stuff, or at answering questions.

Surprise your audience

Surprise is the only way to elicit an emotional reaction from your audience, whether that be laughter, sadness, or anger.

Tips to preserve surprise

- Don’t open with a thesis statement, saying what the story is about.

- Enhance the surprise by using contrast. For example, in This is Going to Suck, Dicks talks about his hopes for a perfect Christmas.

- Use stakes. For example, Dicks gave his audience a Backpack in Charity Thief by describing his plan in detail. Then he left a Breadcrumb to trigger curiosity and false expectations, and used an Hourglass to build anticipation.

- Hide or obscure the critical information. Often you need to reveal pertinent information for a surprise to pay off later, but in a way that won’t ruin the surprise. Some ways to do this:

- Reveal the critical information early on (as far away from the payoff as possible).

- Hide it amongst other unimportant details.

- Hide it with humour, so your audience thinks you only told them that information to get a laugh.

Humour

Humour is optional. Stories should not be solely based on humour, else they will be one-dimensional and forgettable. The goal is not to tell a funny story but to move your audience emotionally. Ideally, you want your audience to experience a range of emotions over the course of your story.

When to use humour

Humour is best used strategically, either at the start or in the middle of your story. Dicks insists that you should end your story on heart, rather than on a laugh:

Far too often I hear storytellers attempt to end their story on a laugh. A pun. A joke. A play on words. This is not why we listen to stories. We like to laugh; we want to laugh. But we listen to stories to be moved.

Humour is particularly useful in the following situations:

- At the start. Starting with a laugh signals to the audience that you’re a good storyteller and relaxes them. It’s also a sign of approval, so can put you at ease.

- Before an emotional moment. Contrast can make the emotional moment pack more of a punch.

- To break the tension. After a story has gotten very tense, you may want to break that tension with a laugh. Similarly, if you’ve just made your audience cry, you may want them to take a breath and collect themselves before you make them cry again. (You don’t want them crying the whole way through.)

- To set up a surprise. See above — you can use humour to hide critical information.

How to be funny (even if you’re not naturally funny)

The two easiest ways to be funny are:

- Milk cans and baseballs. This is just a setup (the milk cans) and a punch line (baseball). You build up your tower and save the funniest thing for last. [There’s not much real advice here. Dicks argues that specificity is funny by claiming that “I’m pouring water over Raisin Bran because I am too stupid and lazy to buy milk” is funnier than “I’m pouring water over a bowl of cereal”. I mean, the former might be funnier (I’m unconvinced), but I doubt it’s because he mentions Raisin Bran. He also claims that some words like “Pop-Tart” are just funny. He may be right, but it’s hardly useful or actionable advice.]

- Babies and blenders. It’s often funny to put together two things that rarely or never go together. Exaggeration is one form of this. You may have to experiment with different combinations to see what gets the most laughs.

Keep your story short

Shorter is better. Many people speak for 8 to 10 minutes; Dicks suggests aiming for 5 to 6 minutes, and no more than 7 scenes (physical locations). The longer you speak, the more engaging you have to be. Expectations are higher. If you’re quick, you don’t have to be nearly as good.

Short stories are harder to craft, because you have to make difficult choices about what to keep in. But you’ll end up with a better story.

Success stories

Sometimes we want to, or are even required to, share our success stories. But success stories are hard stories to tell well because failure is more engaging than success, and you don’t want to sound like a douchebag.

Dicks recommends two strategies:

- Cast yourself as an underdog. People love underdogs. Moreover, seeing an underdog succeed is surprising because we expect underdogs to lose (and hope they win).

- Downplay your accomplishment. For example, you can talk about how have succeeded but still a long way to go. Most accomplishments consist of many small steps, rather than a single great leap, and people prefer such stories. Moreover, overnight success stories can be disheartening and hard for your audience to relate to. Another way to downplay your accomplishment is by emphasising the contributions that others made to your success.

Ending

The best stories are a little messy at the end and leave the audience with unanswered questions. For example, when Dicks first told the Charity Thief story, he told the complete version, ending with a redemption as Dicks more than repays all the money he stole. However, he’s since learned that it’s more effective to end the story early, without any redemption, because it sticks with the audience longer.

A story is like a coat. When we tell a story, we put a coat on our audience. Our goal is to make that coat as difficult to remove as possible. I want that coat to be impossible to take off. Days after you’ve heard my story at the dinner table or the conference room or the golf course or the theater, I want you to be thinking about my story.

The redemption fixes everything and puts the world into order. It’s then easy for the audience to take off the coat and forget about the story. Without the redemption, however, the world remains broken and the story lingers with them.

Telling your Story

Rehearsing

Don’t rehearse in front a mirror (this goes for speeches as well). You’ll never perform or speak in front of a mirror, so this should be the last place you should rehearse. [Obviously people practice in front of a mirror to see how they come across, rather than because they think it will be similar to their actual performance conditions. I agree with Dicks that a mirror can be distracting, though. Recording yourself may be a better way to see how you come off but Dicks does not comment on that.]

Don’t memorise your story. Memorising is bad because you’re less likely to come off authentic and vulnerable. Also, if you memorise your story, you’re more likely to freeze up if you forget a word. Dicks has seen this happen — storytellers just stop speaking for a minute or even longer as they forget their line.

Instead, just remember the first and last few sentences of your story (so you can start and finish strong) and the “scenes” of your story. The scenes are the places where everything, including any internal monologues, takes place. (Remember Dicks’ recommendation to provide a physical location for everything.) If you remember the scenes, then you can recover even if you forget a detail.

Performing for an audience

Don’t worry about your appearance or your hands. Just leave them be and concentrate on your story.

Make eye contact when possible (sometimes it won’t be possible, such as if a spotlight is shining in your eyes). But you don’t have to make eye contact with every person. Find three people — one on your left, one on your right, and one in the centre — who are nodding or smiling as you tell your story. Use them as guideposts and make eye contact with them.

Always use a microphone when one is available, as hearing impairment is a lot more common than you think. But using a microphone doesn’t mean you can speak super softly; you should still try to project to the back of the room. Also, learn to use the microphone and take time to make sure it’s perfectly adjusted. Every second you take will feel very long to you, but very short to your audience.

You may feel emotional when telling parts of your story, which is good. But if you don’t want to become too emotional, Dicks recommends trying to shift your perspective from a first person view to a third person out of body view when reliving your story. (He uses the example of racing video games, where you can change the perspective from being in the driver’s seat to being “above” the car, looking down on it from outside.) Another tip is to practise repeating the most emotional sentences to yourself, to take away some of their power.

Further tips and notes

- Profanity and vulgarity. Stories without profanity or vulgarity are accessible to a larger audience. For example, Dicks doesn’t swear much, which makes it easier for large organisations, religious institutions and schools to hire him. Dicks suggests swearing only:

- if it really is the best word in the situation (e.g. Dicks always calls his former stepfather an “asshole” because he thinks that is the best word to describe him);

- you’re repeating what someone else said, verbatim;

- to convey extreme emotion, especially anger and fear; or

- for humour (but don’t rely solely on profanity for humour).

- Be careful about accents. Don’t put on an accent unless it’s your parents’ or grandparents’, and possibly the accents from the area you grew up if you’re the same race as the people you’re imitating. If in doubt, don’t.

- Stories with other people. You can change people’s names to protect their anonymity. A small change (e.g. Bobby instead of Barry) is easier to remember. But Dicks advocates using the real names of any “villains” who deserve it (such as his former stepfather). Sometimes a name change will not be enough. Some stories might irreparably damage relationships with people you care about, or expose someone’s secrets. Those stories are simply not worth telling.

Other Interesting Points

- No one will ever care about your drinking stories as much as you, and drinking stories will never impress the type of people you want to impress. [Very true.] Drinking stories that take place between the ages of 40 to 70 are usually sad and pathetic (over 70, such stories become acceptable again).

- No one wants to hear about your vacation. Anyone who asks is just being polite. [Also true.]

- Dicks feels deeply hurt when people doubt his stories. In his storytelling career (over 6 years at the time of writing), only 5 people has, in front of him, doubted whether his story was true. Each one of those occasions still hurts him — he even recounts them in the book. [I found it surprising how much this doubt seemed to affect him. In one example, he says a magazine editor “doubted that my moment of revelation was as succinct and powerful as I made it out to be”. Dicks doesn’t say which story that was, but this seems to be a very reasonable doubt to me, particularly as he claims conflation is a “permissible” lie in storytelling.]

My Thoughts

Storyworthy wasn’t quite what I expected. I had wanted a book that might help me tell stories to better persuade others of my arguments. Something like How Minds Change, perhaps. Instead, Storyworthy is about telling personal stories in a performance or entertainment setting. I’d never heard of The Moth before and didn’t even know such storytelling events existed (they don’t where I live).

But Storyworthy can be worth reading even if you have zero interest in public storytelling. For one, it’s interesting to get a “behind the scenes” look at a master storyteller’s process. Like Dicks’ students, I found some comfort in knowing that his early story attempts are very messy, and that he puts a lot of thought into a short, 6-minute story. I also started doing Homework for Life as Dicks suggests, largely because I am a sucker for ideas that help me capture and remember my life. (Besides, I wanted more practice building tiny habits.)

Overall, I found Storyworthy to be an enjoyable and useful read. Dicks is a compelling writer and he illustrates his advice with reference to stories he’s told. The writing is also very tight. He makes his points simply and clearly, without too much repetition. Structurally, the book was logical and easy to follow. Interspersed between the chapters are short “Story Breaks”, pleasant little interludes from the main advice.

It’s important to remember that, as Dicks says, storytelling is an art, not a science. It’s easy to forget this because, despite Dicks’ disclaimer, his writing style is rather prescriptive. After reading Storyworthy, I listened to some stories on The Moth Podcast. Most stories deviated from Dicks’ advice in one way or the other, with mixed results. Some redemption stories, in my opinion, still made great stories. Yet I did find myself losing interest in stories which did not reveal an early “Elephant”. So there’s something to be said for Dicks’ advice.

Buy Storyworthy at: Amazon | Kobo <– These are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase. I’d be grateful if you considered supporting the site in this way! 🙂

Have you started “Homework for Life” or picked up some helpful tips for telling your next story? Share your thoughts about Storyworthy in the comments below!

If you enjoyed this summary of Storyworthy, you may also like:

2 thoughts on “Book Summary: Storyworthy by Matthew Dicks”

The comment about drinking stories is hilarious!

Oops, did I just set the expectations too high there? Haha

Can you share one of your story ideas?

Yeah I have a friend who loves to tell drinking stories and I often zone out when he does, so I appreciated that comment. (He is approaching 40, too!)

Hmm… one idea I jotted down recently was inspired by a lunch with some former colleagues. It got me thinking about how saying goodbye to people now in my 30s feels different from back in my 20s. In my 20s, it felt like everyone was leaving, and I always kind of assumed I would see those people again. Years later, I realise I *haven’t* seen some of those people again – or even if I had, many of those relationships had changed as our paths had diverged. So the goodbyes now felt more poignant.