In The Psychology of Money: Timeless lessons on wealth, greed, and happiness, Morgan Housel explains why success with money has more to do with behaviour than knowledge.

Estimated reading time: 25 mins

Buy The Psychology of Money at: Amazon (affiliate link)

Key Takeaways from The Psychology of Money

- How to be successful with money:

- It’s more about psychology and behaviour than being smart.

- Aim to be reasonable, not rational — what matters is what helps you sleep at night, not what is optimal in theory.

- The key steps involve:

- saving (even if you don’t have a particular goal);

- investing for the long-term; and

- surviving.

- Know what game you’re playing and be wary of taking cues from others. Everyone thinks about money differently, based on their own experiences.

- The future is highly uncertain:

- It’s hard to understand the past, because luck plays a role in outcomes—and a bigger role in cases of extreme success or failure.

- It’s harder to predict the future because what surprises us keeps evolving over time. (But some basic features of human psychology are pretty stable.)

- It’s even hard to predict what you will want in the future because people change over time.

- How to deal with uncertainty:

- The good news is you can be wrong half the time and still make a fortune.

- Build in a margin of safety to increase your chances of staying in the game.

- Avoid risk of ruin — be wary of leverage and single points of failure. And don’t risk things that aren’t worth risking, like your reputation or freedom.

- Stay away from extremes to minimise your chance of regret.

- The value of wealth:

- Wealth won’t make people like or respect you. Wealth is what you don’t see—the financial assets that haven’t been converted into tangible things.

- The real value of wealth is flexibility and control over your time.

Detailed Summary of The Psychology of Money

How to be successful with money

It’s more about psychology and behaviour than being smart

Doing well with money is not about what you know, but how you behave. In finance can someone with no college degree, formal experience or connections and massively outperform another person with the best education, training and connections.

Example: The wealthy janitor vs the bankrupt MBA

Ronald Read, a humble janitor, died at the age of 92 with around $8 million. He hadn’t won the lottery or received a big inheritance. He’d just been a diligent saver and invested in blue chip stocks over a long time.

On the other hand, Richard Fuscone was a finance executive with a Harvard MBA, who seemed to have all the advantages Read didn’t. Fuscone had become so successful that he retired in his 40s to become a philanthropist. But he also spent big—his mansion cost more than $90,000 a month to maintain. He was bankrupted in the 2008 financial crisis.

Behaviour is greatly underrated and hard to teach, even to smart people.

Aim for reasonable, not rational

You are a person with emotions. So don’t try to make the decisions that would be optimal for an emotionless robot, but which cause you to lose sleep at night. Aim for decisions that are just “reasonable”, which you can stick with in the long-run. A strategy that works in theory, but requires you to stick with it even if you lose 100% of your savings, is not reasonable.

Few people make financial decisions purely with a spreadsheet. They make them at the dinner table, or in a company meeting.

It’s helpful to think of market volatility as a price or fee. High returns do not come for free—its price is high volatility and risk. You can pay this price by accepting the volatility, or you can find an asset with less risk and a lower pay-off. Trying to get high returns without the volatility (e.g. by timing the market) is like trying to steal a car. A few get away with it. But far more do not, and end up worse off. If you think of volatility as a fee, the trade-off is clearer and may be easier to stomach.

Save, invest and survive

Save

Building wealth is more about your savings rate than it is about your income or investment returns. You can build wealth without a high income, but not without a high savings rate. And, unlike investment returns, your savings rate is mostly within your control.

To increase your savings rate, you have to spend less. You spend less if you desire less. And you desire less if you care less about what others think of you. So one of the most powerful ways to increase your savings rate is to increase your humility. Again, success with money comes back to psychology than knowledge.

You don’t need a specific reason to save, either. Saving for a specific goal may make sense in a predictable world, but the world isn’t predictable. Savings gives you flexibility and options, so you should save simply to hedge against life’s unpredictability.

Invest for the long term

Investments compound, which creates exponential growth. Since we intuitively think in linear terms, we tend to underestimate the power of compounding even when we should know better. When growth is exponential, even small changes in assumptions can lead to vastly different numbers in the long run.

Example: Warren Buffett’s secret is time

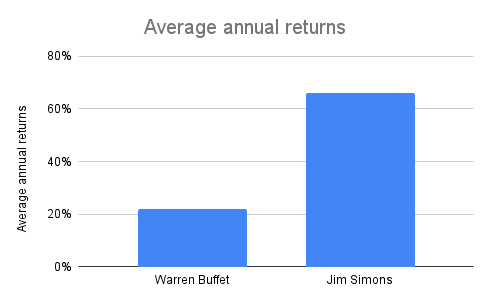

Warren Buffett has compounded money at around 22% annually. This is an impressive return, but it’s only a third of what Jim Simons, head of a hedge fund, has achieved—66% annually since 1988. No one else comes close to this record.

Yet, at the time Housel wrote this book, Buffett’s net worth was $84.5 billion. Simons’ was only $21 billion.

Buffett is so successful because he’s been investing seriously since he was 10 years old. When Buffett was 30, his net worth was already $9.3 million (adjusted for inflation). Simons, by contrast, only hit his investment stride when he reached 50 years old. [See Phil’s comment below which points out that another key difference between the two is that Buffett was able to compound his 22% gains while Simons‘ firm had to return capital to investors each year as they exhaust their investment opportunities. So that is a big part of the difference in their net worths, which Housel doesn’t mention.]

If Buffett had been a more normal person who started investing at 30 (with, say, $25,000) and retired at age 60, his net worth would be around $12 million, even assuming the same 22% annual returns. That’s 99.9% less than his actual net worth of $84.5 billion.

Good investing isn’t necessarily about earning the highest returns, because the highest returns tend to be hard to repeat. It’s about earning “pretty good” returns that you can stick with in the long run, so that compounding runs wild.

… the most powerful and important book should be called Shut Up And Wait. It’s just one page with a long-term chart of economic growth.

Survive

Since compounding is so powerful, money success comes down to survival. You only get the extraordinary results of compounding if you can survive all the inevitable ups and downs over time.

Getting money and keeping money are different skills:

- Getting money requires taking risks and putting yourself out there. There are a million different ways to get wealthy and a million different books on it.

- Keeping money requires the opposite. The only way to stay wealthy is some combination of frugality, humility, and paranoia.

Housel recommends a ‘barbell’ approach where you’re optimistic about the long-term future, but paranoid to avoid any short-term landmines along the way. In the long-term, optimism is the best bet because the world tends to get better for most people most of the time (even though pessimism may sound smarter and be more newsworthy). But in the short-term, there’ll still be setbacks, so you shouldn’t get complacent.

Know what game you’re playing

Bubbles form when long-term investors take their cue from short-term traders

Many finance decisions depend on watching what other people do. But the idea that assets have a single, rational price has done a lot of damage. Since investors have different goals and time horizons, prices that make sense to each of them can be vastly different. If you don’t know why someone behaves like they do, you won’t know how long they’ll keep behaving the same way.

Day traders have incredibly short time horizons. They’re concerned about a stock’s momentum (whether it’s been moving up consistently for a while), not its underlying value (how much money the company will generate in the future). The same is true for housing. A very high price can make sense if your plan is to flip the house within a few months. It won’t matter to the flipper what the house’s price-to-rent ratio is.

When a stock’s momentum attracts enough short-term investors, a bubble can form as long-term investors start taking their cues from short-term traders. Bubbles are less about valuations rising (that’s the domain of long-term investors) and more about time horizons shrinking.

Record trading volumes in the dot-com era

During the dot-com era, trading volumes kept setting new records. The average mutual fund had 120% turnover in 1999.

Many investors who owned Yahoo! stock in 1999 had time horizons so short that it made sense for them to pay ridiculous prices. It didn’t matter to them whether the price was $5 or $500 a share, as long as it moved in the right direction that day.

If you don’t know what game you’re playing, you’ll never hit “enough”

The hardest financial skill is getting the goalposts to stop moving. In developed countries, a lot of consumer spending is socially driven. But while we might see how other people spend on cars, homes and clothes, we don’t know their goals or time horizons.

Wealth is relative to what you need, but if your ambition increases faster than your satisfaction, you’ll always feel as if you’re falling behind. The ceiling of social comparison is so high that almost no one can ever hit it. Many of the wealthiest people do not have a sense of “enough”:

- Rajat Gupta, a successful businessman worth $100 million, wanted to be a billionaire so badly that he resorted to insider trading. He ended up going to prison and ruining his reputation.

- Bernie Madoff used to be a legitimately successful businessman making millions of dollars before he started a massive Ponzi scheme.

- Rihanna nearly went bankrupt from overspending and sued her financial advisor.

There are less extreme, non-criminal examples of people not sensing their “enough” and only stopping when they are forced to. Something as innocent as burning out at work can be a sign you don’t know when is “enough”.

Everyone thinks about money differently

Every person thinks about money differently depending on their own experiences with money (especially experiences in their early adult years).

This means people go through life with completely different views on money simply depending when they were born. A 2007 study found that those who born in the 1960s, who grew up in periods of high inflation, invested less in bonds later in life. Similarly, those born in the 1970s, growing up when the stockmarket was strong, were more likely to invest in stocks later in life.

Your personal experiences with money make up maybe 0.00000001% of what’s happened in the world, but maybe 80% of how you think the world works

Even when people do crazy things with money, it doesn’t mean they’re crazy. Their financial decision may not make sense to you, but it may make sense given their assumptions.

The future is highly uncertain

Everyone’s view of the world is incomplete. We often don’t realise this, because we fill in gaps to form a coherent explanation that seems to make sense. We desperately want to believe the world is understandable and controllable, even when it’s not.

[A]strophysics is a field of precision. … Business, economics, and investing, are fields of uncertainty, overwhelmingly driven by decisions that can’t easily be explained with clean formulas, like a trip to Pluto can. But we desperately want it to be like a trip to Pluto.

It’s hard to understand the past, because of luck

It may seem easy to explain an event with the benefit of hindsight, but we often overlook the role of luck because it’s so hard to quantify.

We prefer simple, clean stories of cause-and-effect that explain why we succeeded or failed. It’s demoralising to attribute our own success to luck, and rude to attribute others’ success to it. But there are many forces outside our control that influence whether we succeed or fail.

Example: Bill Gates vs Kent Evans

Bill Gates was lucky. Yes, he was incredibly smart, hardworking and visionary. But he was still lucky in that he went to one of the only high schools in the world that had a computer at that time. Even university graduate schools didn’t access to a computer as advanced as the one Gates had access to in the 8th grade. The odds of Gates having access to that computer were roughly 1 in a million.

Kent Evans unlucky. He was Bill Gates’ best friend in the 8th grade. According to Gates, Evans was the best student in the class, and just as skilled with computers as he was. Evans also shared Gates’ business mind and ambition. But Evans died in a mountaineering accident before he graduated high school. The odds of dying on a mountain in high school are also around 1 in a million.

For every Bill Gates there is a Kent Evans who was just as skilled and driven but ended up on the other side of life roulette.

Bill Gates himself calls success “a lousy teacher”. The same is true for failure. People assume that a failure implies they made a bad deciison, but sometimes it just reflects the reality of risk and uncertainty. [In poker this is called “resulting”—judging a decision based on how it turned out rather than how sound the decision was when you made it.]

Another reason why understanding the past is hard is because we tend to focus on the extreme examples. Those paths tend to be the least generalisable, because they’re more likely to be influenced by extreme luck or risk. Finance is full of “long tails”, where a small number of events can account for the majority of outcomes. Anything huge, profitable, famous or influential is therefore due to a tail event.

Many successes and failures became so because of leverage, which magnifies both gains and losses, and lack of diversification. In 2013, Warren Buffett said he’d owned 400 to 500 stocks during his life and made most of his money on just 10 of them. Benjamin Graham is considered one of the greatest investors of all time, yet he owes most of his success to a large chunk of GEICO stock, which he admits breaks nearly every diversification rule. This means we should focus more on broad patterns than on studying why specific players succeeded or failed.

It’s harder to predict the future

We’re very, very bad at making market forecasts or predicting recessions.

Part of why major events were so impactful was because we weren’t prepared for them. Think of the Great Depression, World War II, the dot-com bust, September 11th and the Global Financial Crisis. We often use such events as a benchmark for our “worst-case scenarios” for the future. But those had no precedent when they occurred. What surprises us keeps evolving. There’s no reason to assume the best and worst events in the past will match the best or worst events of the future.

The correct lesson to learn from surprises is that the world is surprising. Not that we should use past surprises as a guide to future boundaries …

The further back you look, the less likely that the past’s lessons will apply today. Many things that we take for granted today are not actually that old:

- There were virtually no technology stocks 50 years ago, but they make up more than 20% of the S&P 500 index today.

- The idea of retirement as an entitlement was only born in the 1980s.

- Index funds are less than 50 years old.

- The first credit card was only invented in 1950.

This doesn’t mean we should ignore history altogether. It just means that, the further back we look, the more general our takeaways need to be. Things like how people respond to incentives or behave under stress tend to be pretty stable.

It’s even hard to predict ourselves

We all change, and most of us change more than we expect. Daniel Gilbert has written about the “End of History Illusion”, which shows that people of all ages tend to be aware of how much they’ve changed in the past, but underestimate how much their personalities and desires will change in the future.

This makes it hard to set goals and plan for the future. Compounding means it’s the long-term that matters—not just in finance but also in careers and relationships. But will our future selves like what our past selves have done for them?

We should accept that it’s okay to change our minds. Don’t stick to a career only because it’s what your 18-year-old self wanted. The sooner you accept the reality of change and move on, the sooner you can get back to compounding.

How to deal with uncertainty

You can be wrong half the time

The bad news is that the future is really hard to predict. But the good news is you can be wrong half the time and still make a fortune. One reason is because of extreme tails—one major success can make up for many losses.

40% of companies lost 70% of their value

J.P. Morgan published the returns for a broad index of the 3,000 largest US public companies since 1980.

Forty percent of those companies lost at least 70% of their value and never recovered over this period. And yet the index has increased more than 73-fold over that time.

This is because almost all of the index’s overall returns came from the top 7% of companies, and these companies significantly outperformed the average.

The fact that we can fail so often and still succeed is not intuitive. We generally only see the successful, finished products; we don’t see the losses along the way.

Build in a margin of safety

Over the past 170 years, the standard of living in the US increased 20-fold. Yet this same period experienced:

- 9 major wars;

- 4 president assassinations;

- 48 years of recessions; and

- at least 12 times when stocks lost a third of their value.

Your plan must therefore allow a margin of safety (also known as room for error or slack) so that you survive long enough for compounding to pay off. This can come in many forms—cash, frugality, flexible thinking, or a loose timeline.

No one wants to hold cash with 0% returns when stocks are going up by 10% or 20%. But if that cash prevents you from having to sell your stocks when the market drops or gives you the option of holding out for the right job, the actual return on that cash can be extraordinarily high.

A margin of safety is often mistaken for simply being “conservative”, but they’re different things. Being conservative means avoiding risk, while a margin of safety raises your chances of success at a given level of risk.

Avoid risk of ruin

Statistically, Russian roulette should work. But it’s not worth playing, because the risk of ruin is too high.

Two things that increase risk of ruin are:

- Leverage. Taking on debt to invest can convert routine risks into potential risks of ruin.

- Single points of failure. You can’t plan for unknown unknowns. The best you can do is to avoid single points of failure by having backups upon backups. With money, the biggest single point of failure is not having savings and relying solely on your paycheck to fund short-term spending.

Example: Leverage when buying a house

Quick finance lesson here (not from the book). If you buy a house with a mortgage, you’re taking on leverage. This supercharges both your gains and your losses.

Say you buy a $500,000 house with a $100,000 deposit and a $400,000 mortgage.

If the house price rises 20% to $600,000, your equity stake has doubled. You still owe $400,000 but if you sell the house, you’ll pocket $200,000. While your return would have been only 20% if you’d paid for the house in full, it becomes a 100% return thanks to leverage.

But the converse is also true. If the house price drops 20% to $400,000, your equity stake has vanished. You still owe $400,000 but if you sell the house, you’ll pocket nothing. What would’ve been just a 20% loss becomes a 100% loss.

Many people don’t appreciate this and believe that buying a house is “less risky” than buying stocks. My short example shows why this is not true if you’re buying housing with a mortgage. Plus, if you’re buying a single house, you have an extremely undiversified, hard-to-sell asset, which are other sources of risk — e.g. what if a natural disaster strikes your property? What if you discover weathertightness issues? Yet buying multiple houses will likely require increasing your leverage.

This isn’t to say that buying a house is a bad decision. It’s just riskier than many people assume.

You have to take risk to get ahead, but some things in life are just not worth risking, no matter the potential gain. Your reputation. Freedom and independence. Family and friends. Love. Your best bet at keeping these things is knowing when to stop taking risks that might harm them. This means knowing when you’ve reached “enough”.

If you risk something that is important to you for something that is unimportant to you, it just does not make any sense.

Stay away from extremes

Since we can’t know for sure what our future selves will want, Housel suggests staying away from extremes. For example, when you’re young, don’t assume you’ll be happy with a very low income when it comes time to raise a family or retire. But don’t assume you’ll be glad you spent your young and healthy years working endlessly, either.

Regret is particularly painful when you abandon a previous plan and feel you have to run twice as fast in the other direction to make up for it. Balance increases the chance you can stick to your plan in the long-run and avoid future regret. Extremes increase the odds of regret.

The value of wealth

Wealth won’t make people like or respect you

Many people splash their wealth around because they want to signal to others that they should be liked and admired.

But it’s a mistake to think wealth will get you respect and admiration, especially from the people whose respect you care about. When other people see your wealth, they’ll use it as a benchmark for their own desire to be liked and admired and bypass admiring you.

People admire nice cars, not the drivers in them

When Housel worked as a valet, he got to drive cool and expensive cars. He’d dreamed about having one of his own, because he thought it would send such a strong signal to others that he’d “made it”.

But the irony was he rarely ever looked at the drivers of the cars. It’s not like he’d see someone driving a nice car and think the driver was cool. He would just admire the cars and imagine himself in the driver’s seat.

If you want respect and admiration, seek humility, kindness, and empathy. Those will bring you more respect and admiration than wealth ever will.

Wealth is what you don’t see

We can’t see people’s bank or brokerage accounts, so we rely on outward appearances. But people who flash wealth around don’t necessarily have it.

If someone has spent $100,000 on a car, all you know is that they have $100,000 less than they did before. The world is filled with people who look modest but are actually wealthy and people who look rich who are on the brink of insolvency.

… if you spend money on things, you will end up with the things and not the money.

Wealth is financial assets that haven’t been converted into “stuff”. It’s the nice cars not purchased. The diamonds you haven’t bought.

The real value of wealth—flexibility and control over your time

So what’s the point of wealth if not to buy cars, diamonds, respect and admiration?

Wealth is an option you haven’t taken yet. Its value lies in giving you options and flexibility to buy things later.

One of the greatest things wealth can do for you is to give you control over your time. Though there’s a lot of variation in what makes people happy, feeling able to control one’s life is a pretty dependable predictor. A small amount of wealth means you can afford to take a few days off work when you’re sick. A bit more means you can hold out for a better job if you’re laid off, instead of taking the first one you find. Even more wealth can let you retire when you want to, instead of when you have to.

Housel’s personal approach to money

Housel’s financial goal has always been independence—doing only the work he likes, with people he likes, on his own terms.

His household finances are pretty simple—basically a house, checking account, and some low-cost index funds. Their lifestyle is pretty frugal because they got the goalposts to stop moving early on, even as their incomes increased. The things they enjoy—like going for walks, reading, podcasts—don’t cost much, so they don’t feel like they’re missing out.

Everyone should pick an investment strategy that has the highest odds of successfully meeting their goals. For most, that probably means dollar-cost averaging into a low-cost index fund over the long-term. But Housel doesn’t have anything against active stock-picking. He thinks it is possible to beat the market—it’s just harder than most people realise. And if you can meet your goals without having to take on added risk, what’s the point of even trying to beat the market?

Housel admits he’s made financial decisions that are not optimal on paper. For example, they paid off their mortgage when interest rates were incredibly low, and keep more of their net worth in cash (around 20% of their non-housing assets) than most financial advisers would recommend. These aren’t decisions Housel is recommending to others—but it works for them and gives them peace of mind.

My Review of The Psychology of Money

I found this to be a surprisingly good read, especially for a pop-psychology/finance book. Housel’s writing style is similar to Gladwell‘s in that he uses compelling stories and analogies to make his points, rather than hard data. And, like Gladwell, Housel is a journalist whose aim is to bring ideas that are already well-understood in certain circles (like margins of safety and financial independence) to a wider audience. He does this very effectively—at a mere 256 pages, The Psychology of Money is short and incredibly easy to read. Housel also has a talent for capturing insights with pithy quotes.

One minor quibble I had is that Housel can be prone to exaggeration. There were many statements like “the most important thing is” or “if I had to summarise this in a single word” or “tails drive everything“, which felt a bit irritating. But the underlying advice is sound, and much of it applies not just to money but to life more generally.

Housel also did a great job distinguishing between avoiding risk of ruin and general risk aversion, which is more nuance than I expected from a book like this. I do think he could’ve explained leverage better because, in my experience, it’s quite poorly understood (which is why I added a small explainer above).

Housel’s money philosophy seems to align broadly with the FIRE community’s, with more emphasis on financial independence (FI) and less on retire early (RE). His writing comes off far less extreme than, say MrMoneyMustache‘s. While I enjoy and have learned a lot from MrMoneyMustache, I wouldn’t recommend him to most of my friends—but I could see myself recommending The Psychology of Money.

Let me know what you think of my summary of The Psychology of Money in the comments below!

Buy The Psychology of Money at: Amazon <– This is an affiliate link, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through it. Thanks for supporting the site! 🙂

If you enjoyed this summary of The Psychology of Money, you may also like:

5 thoughts on “Book Summary: The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel”

I enjoyed the book when I read it a few years ago, but one particular thing in it irritated me and it’s something you mentioned. It’s the Warren Buffett and Jim Simons comparison.

The difference between the two is not time. It’s that Warren Buffett was actually able to compound his wealth, while Jim Simons’ capacity for exploiting his edge was much more limited. 66% is much much higher than 21% if it compounds, but it doesn’t.

To see this, think about what it would mean if Jim Simons compounded at 66% from when he started in 1988. It would mean that his starting capital was…. $1900.

Or put it another way – the book was published in 2020. If Jim Simons could compound at 66% and Buffett at 21%, it would mean Jim Simons overtakes Buffet in 2025 (with $265b, to Buffet’s $219b). So it would be saying that Jim Simons overtook Buffet in 2025, despite Buffett starting his first partnership in the 1950s, and Jim Simons starting with $1900 in 1988. Time is not very impressive when you put it like that. 66% is impressive!

Basically, Renaissance Technologies (Simons’ firm) cannot compound capital. They return all profits to investors each year, because their opportunity set becomes exhausted.

Overall I enjoyed the book though. His next book was quite a bit weaker – just seemed like a collection of lightly edited blog posts.

Thanks for that explanation – I’ve added a note in the summary to refer to your comment.

I didn’t fact-check that claim but I did do a rough calculation for the claim that if Buffett had been more of a normal person and started investing at 30 and retired at 60, he’d only have around $12 million, which seemed to check out. Of course, even after Buffett retired, he could still keep compounding at a more normal growth rate like 7%. But he’d still be well below $100m which is much less than $84.5 billion.

So I think time is still pretty impressive – but, yes, 66% investment returns are very impressive.

Also thanks for the heads-up that his next book is weaker. I’ll give that a miss.

The influence from Nassim Taleb comes through quite strongly, specifically regarding uncertainty of the future and how to deal with it. A lot of the tidbits here are reminiscent of the Incerto series – profiting off long tails, avoiding risk of ruin, the role of luck/randomness in success. FWIW Taleb was a finance guy too

Yeah, I don’t think any of Housel’s ideas are original (he’s more of a journalist than a finance guy) and I’m not surprised to hear that Taleb’s influence comes through. I still haven’t read Taleb’s books – I tried Antifragile once but didn’t gel with his writing style. I wonder if his ideas have almost been too successful – like, they’ve been repeated so much since that they won’t sound that original if I read him now in 2024.

Haha yes his writing style is very distinct… comes across as the stubborn uncle at the dinner party. I think that has actually helped keep his books evergreen – his ideas may have caught on, but no one puts it quite the way he does! (for better or for worse)