This summary of Why Are the Prices So D*mn High? Health, Education and the Baumol Effect seeks to explain why it seems like prices in education and healthcare keep rising.

Note that the book was published at the start of 2019 and is about the long-run trend of increasing prices in healthcare and education since 1950. It is not about the surge in inflation post-Covid.

Estimated time: 19 mins

Download Why Are the Prices So D*mn High? for free in PDF and epub

Key Takeaways from Why Are the Prices So D*mn High?

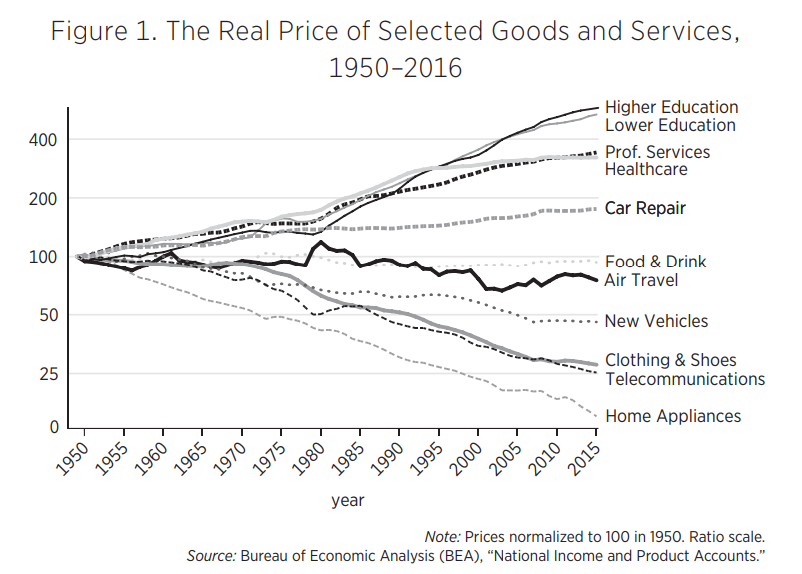

- Since 1950, manufactured goods have gotten much cheaper while costs in education, healthcare, and other service industries have kept going up.

- Usual explanations for the rising prices include:

- Increasing quality;

- Waste and efficiency;

- Government intervention; and

- Increasing market concentration.

- However, none of these can explain the long-run trend of rising prices under a variety of regulatory, legal, and economic environments.

- Instead, the best explanation for the long-run trend is the Baumol effect:

- All prices are relative. Prices are ultimately opportunity costs, and it is simply impossible for all opportunity costs to fall.

- So if you have uneven productivity growth across sectors, relative prices will rise in the slower-growing sectors.

- Price increases have been particularly large in service sectors that rely heavily on skilled labour. Education and healthcare are two examples, but we also see this in law, accounting and car repair.

- Even as prices have gone up in education and healthcare, real resource use has also gone up. This is consistent with the Baumol effect, but not with the waste and inefficiency explanations.

- The Baumol effect suggests rising prices are not necessarily bad. Paradoxical as it may seem, a product can rise in price and become more affordable at the same time.

Detailed Summary of Why Are the Prices So D*mn High?

There are lots of graphs (33 in total) where Helland and Tabarrok go through the evidence in detail. Since this is a summary, I’ve focused more on the explanations, but I’ve picked out a few graphs that I liked.

Why have prices in education and healthcare increased so much since 1950?

Since 1950, most manufactured goods have gotten much cheaper. When microwaves first became available to consumers, they cost $11,600 in 2016 dollars. New vehicles today are about half of what they cost in 1950.

Over this same price, the prices of many services has increased. For example, while the cost of purchasing a vehicle has halved, the cost of servicing it has nearly doubled.

Helland and Tabarrok focus on three service industries:

- Lower education (K-12) — real expenditures per student have increased around five-fold since 1950;

- Higher education (college) — around the same as lower education;

- Healthcare — real expenditures per person have increased almost nine-fold since 1960. [The graph seems to show healthcare costs growing more slowly than education, though. I don’t know why.]

The usual explanations for these price increases include:

- Quality — we’re paying more because we’re getting better services;

- Waste or ‘bloat’ — we’re not getting better services, there are just more middlemen taking a cut or other inefficiency.

- Government intervention — this is a subset of the waste argument

- Market power — increasing market concentration may reduce competition and therefore lead to higher prices.

Helland and Tabarrok address each of these in turn, and think there could be some truth in them. But the better explanation for the long-term trend is the Baumol effect.

[A]ny “explanation of the day” for rising prices in education, healthcare, and the arts must come to grips with the fact that rising prices have been a prominent feature of these industries for well over 100 years and under a wide variety of regulatory, legal, and economic environments.

Quality

For education, Helland and Tabarrok don’t think quality improvements explain the roughly five-fold price increases:

- Test scores certainly haven’t improved by that much;

- Classrooms haven’t changed that much;

- Time to completion in college has increased, which suggests students may be learning more slowly; and

- The research share of higher education spending has not changed much since 1980.

For healthcare, the quality explanation is more plausible. Life expectancy in the US has increased considerably, both at birth and at age 65. And healthcare is somewhat of a luxury good—the better your life is, the more healthcare you want (see Hall and Jones (2007)). Some have suggested that increases in income may even be the primary reason for rising expenditures in healthcare. While the US spends more on healthcare per capita than any other country, it also has a higher GDP per capita than any other large country. So to the extent that this is driving high healthcare expenditures, it’s no more a concern than increased spending on, say, tourism.

Helland and Tabarrok acknowledge that it’s hard to say with certainty whether quality improvements caused the rising costs in healthcare. They also note that many increases in life expectancy came from better knowledge, which does not necessarily increase costs.

Waste or bloat

The bloat theory is popular because it is easy enough to find examples of bloat.

The two main bloat theories in education are that rising prices are due to increases in:

- Student amenities (e.g. nice buildings, climbing walls, lazy rivers in college); or

- Administrator salaries (e.g. David Graeber has called “academic administrator” one of the biggest bullshit jobs).

In higher education, the administrative share of spending has been pretty consistent since 1980. The equipment and plant share (where you’d expect to see stuff like climbing walls) has actually declined.

In lower education, the numbers of principals and administrators did double between 1970 and 1980. But they stopped after that, yet expenditures kept growing. Plus, the base numbers are so small (around 0.4 per 100 students) that the overall increase in administrators is negligible.

A bloated little toe cannot explain a 20-pound weight gain.

In healthcare, contrary to popular belief, the growth rate for per capita healthcare costs has been declining over time. It was around 6.2% during the 1960s; in recent years, it’s around 2%. Costs related to medical malpractice are also unlikely to be the culprit as they’re too minor—medical malpractice payments accounted for only 0.12% of national healthcare costs in 2017. There are plenty of plausible reasons why US healthcare is more expensive than it needs to be. However, these don’t explain why costs have grown over time.

Government intervention

One hypothesis is that certain government interventions like increased regulation raises costs.

In education, Helland and Tabarrok are sceptical of this explanation. They consider lower and higher education separately because the two sectors are very different. Lower education is produced by government monopolies with little market pricing, while higher education is produced in a competitive market with market prices.1Though college subsidies exist, the costs are still mostly borne by students and their parents. Students have also been paying a larger share of education costs over time—between 2000 and 2015, the student share increased from 50% to nearly 75%. But despite their very different competitive structures, costs in lower and higher education have steadily increased at comparable rates. And in higher education, the growth in costs has been similar at both private and public institutions.

It is difficult for the same theory to explain why both higher education and K–12 education should bloat. Indeed, one of the signs that bloat is not a productive theory is that bloat in higher education is often blamed on competition—a common term is the “amenities arms race”—while in K–12 education, bloat is often blamed on lack of competition.

For healthcare, they observe that the US healthcare system has experienced massive changes since 1960 including: the rise of third-party insurance; introduction of Medicare and Medicaid; and the Affordable Care Act. But over this period, healthcare cost continued to steadily rise. So while those policy changes may explain deviations from the trend, they don’t explain the long-term trend itself. [Tabarrok also points out in the Rationally Speaking podcast that pet healthcare costs have gone up just as much as human healthcare, even though that sector doesn’t get government subsidies and pet insurance is still uncommon.]

Helland and Tabarrok also look at price changes in different industries between 1987 and 2016 compared to changes in the QuantGov‘s regulatory index over that same period. They find no clear correlation. Of course, regulation may still have an impact on productivity and prices. It just doesn’t seem to be the primary factor driving price increases in the long-run.

Market power

Another hypothesis is that prices rise as markets grow more concentrated and firms gain more market power. However, the fact that growth rates for healthcare costs per capita have been declining over time suggests this is not the driver of increased costs.

Across industries, there is a weak correlation between the changes in the level of concentration in an industry and price changes. But the effect is driven entirely by petroleum and coal products and tobacco manufacturing.

The Baumol effect

Helland and Tabarrok think the Baumol effect is the best explanation for rising prices in the long-run. The Baumol effect occurs because all prices are ultimately relative, and productivity growth across different sectors is uneven.

All prices are relative

Behind the veil of money, prices are ultimately relative prices—prices tell how much butter society must give up to get guns. But if butter becomes cheaper and society can buy more butter by giving up the same number of guns, then guns must have become more expensive—it takes more butter to buy the same number of guns.

We are used to thinking about prices as a measure of affordability. In the short-term, this is true. When the price of something falls, it becomes more affordable because incomes are fairly constant in the short term. But over the long-term, this no longer holds. A surprising implication of prices being relative is that it‘s possible for a product to rise in price and become more affordable.

For example, say we got 5x more efficient at producing cars but only 2x more efficient at producing education. The price of education relative to cars would rise. But both cars and education would become more affordable as we can produce more of both at a lower cost.

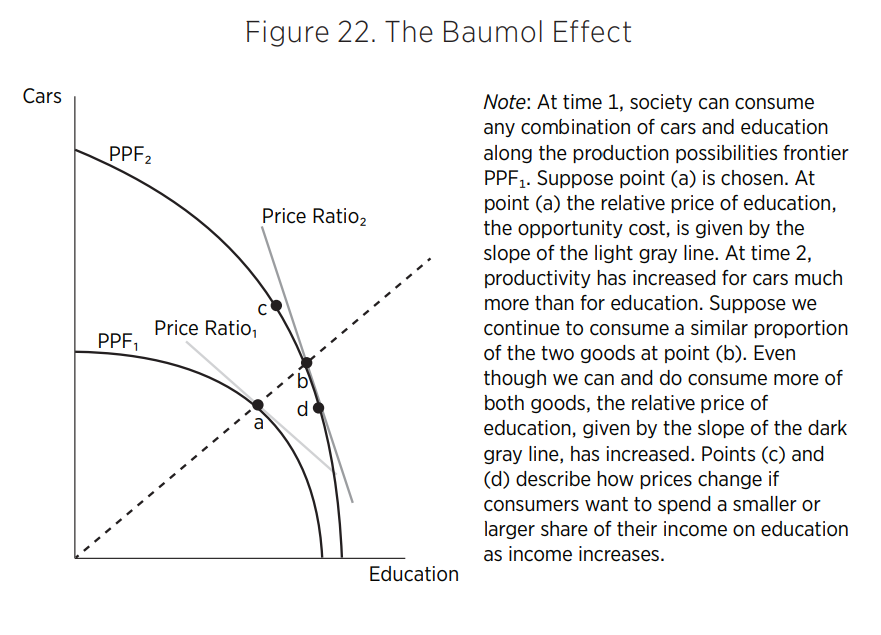

Helland and Tabarrok explain this using Figure 22 below. Don’t worry if you’re not economically-inclined — the key takeaways are simply:

- all prices are relative prices (this shown in the price ratio tangents in the graph);

- over the long-term, relative prices change as we get more efficient at producing some types of products (like cars) than others (like education).

So while your intuition might say that prices fall with economic growth, this is not true over the long term. Since all prices are relative, they cannot all fall at the same time.

Uneven productivity growth

Because the Baumol effect is all about relative prices, it occurs when different sectors grow at different rates.

Example: String quartets

The classical example of Baumol’s effect is the string quartet performance. In 1826, it would take 4 hours to perform a particular composition. Today, it takes exactly as long. Put another way, while most other sectors have experienced substantial productivity growth since 1826, there been zero increase in labour productivity in live string quartet performances.

Listening to a live string quartet has therefore become costlier in relative terms. Since we’ve gotten so much more efficient at producing other goods, we have to give up more of those goods to produce a string quartet performance. The opportunity cost of a string quartet performance has therefore increased.

But the affordability of a string quartet has not changed at all. It takes just as much time to produce as before. There hasn’t been any increase in waste or inefficiency.

… [B]etween 1826 and 2010, the price of a string quartet performance increased by a factor of 23, and yet there has been no increase in quality. But who would expect otherwise?

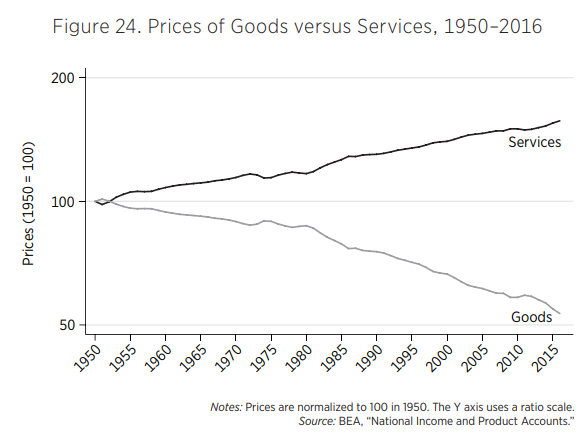

At a high level, we’ve seen much higher productivity growth for consumer goods than for services. Since 1950, prices for consumer goods have fallen by a factor of two (from 100 to 53), while prices for services have increased by around 1.5 times (from 100 to 157).

Data across a wider range of industries is also consistent with the Baumol effect—there’s a clear negative correlation between productivity growth2“Productivity” growth refers to increases in outputs that cannot be explained by increased inputs (increased capital, labour, energy, materials or services). Technological advancements that let us produce the same or more outputs with fewer inputs therefore increase productivity. and industry prices. The computer industry experienced large productivity increases and falling prices, while pharmaceuticals had less productivity growth and rising prices. These effects persist even after controlling for regulation and market concentration.

For both education and healthcare, the fastest growth in costs occurred between 1950 and 1970—the period in which productivity growth in the general economy was fastest.

Slow productivity growth in skilled labour-intensive services

Not all services are alike. Some services like teaching, healthcare or massage are labour-intensive in that they require a person’s time and attention. Other services, like telecommunications, air-travel or online entertainment do not. These are the only services to see significant price declines. If we focused looked at labour-intensive services like healthcare and education, the price increases since 1950 would be even more than the 1.5 times increase we see for services overall.

Another consideration is whether a service uses skilled labour. Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F Katz explain that technology increases the demand for skilled labour while education increases the supply of such labour. Since the 1980s, growth in educational attainment has slowed, creating a shortfall of educated workers. The college wage premium has therefore increased, as have relative prices of goods or services that use skilled labour.

If an industry has low productivity growth and relies heavily on skilled labour, it will see especially large price increases. Education and healthcare use a lot of skilled labour and are examples of two such industries. But there are other examples too, like law, accounting, veterinary services and car repair.

Increasing real resource use

Helland and Tabarrok also look behind prices to real resource use—the number of real resources (people, hours worked) being used in those sectors. If rising prices are caused by increasing waste or inefficiency, you’d expect real resource use to fall as people substitute away from that product or service.

But we see the opposite in healthcare and education:

- In K-12 education, the number of teachers per 100 students almost doubled between 1950 and 2015, and the number of other staff per 100 students has roughly tripled.

- In higher education, the number of faculty per student has increased.

- And in healthcare, the number of physicians and nurses more than doubled between 1960 to 2016.

This increase in real resource use has occurred even as the cost of these resources has gone up:

- In K-12 education, instructional expenditures per teacher (mostly salaries and benefits) increased 2.6x between 1950 to 2013, with the fastest growth between 1950 and 1970.3While the rising cost of labour inputs is the best explanation for the rising cost of education, Helland and Tabarrok aren’t suggesting that teachers are overpaid. They think teachers are earning a relatively normal wage for their level of skill and education. (They earn about 5% more than similar workers in the private sector because of teachers’ unions. But unions can’t explain why teachers’ wages have increased over time—and they certainly can’t explain why faculty compensation has increased.)

- In higher education, faculty compensation has also increased.

- And in healthcare, the real income of both physicians and nurses tripled between 1960 and 2016. No other profession has seen such large increases in that time period.

Increased real resource use against a backdrop of higher costs is entirely consistent with the Baumol effect. Recall that, under Baumol, price increases in health and education are driven by productivity improvements in other sectors. People’s real incomes4By “real income”, Helland and Tabarrok don’t just mean nominal income as adjusted for inflation. They mean the amount of stuff we can produce for the same amount of capital and labour hours. have therefore gone up — i.e. they don’t need to spend as much to make the same amount of manufactured goods. This frees up resources for healthcare and education.

Implications of Baumol

This effect is not a “cost disease”

The Baumol effect is usually called “Baumol’s cost disease”. However, Helland and Tabarrok prefer to call it the “Baumol effect”, because they think the phenomenon is actually a good thing. Over time, goods can increase in price and become more affordable.

People often contrast the tremendous increases in expenditure on education or healthcare with the relatively flat levels of quality and conclude that the increased spending has been fruitless or even wasteful. But the Baumol effect suggests a completely different interpretation.

Waste and efficiency can still exist

The Baumol effect does not explain every case of rising prices. For example, the high cost of infrastructure construction in large cities does not seem to be caused by Baumol. The Baumol effect suggests rising costs and rising purchases. But in urban infrastructure we see rising costs and what appears to be declining purchases. That phenomenon—consumers reducing their purchases in response to higher prices—is consistent with a true cost disease.

Moreover, the Baumol effect doesn’t explain why productivity growth is faster in some sectors than in others. So bad regulations might partly explain why productivity growth in health or education has been slower.

Increasing productivity is still good

The Baumol effect is not a call for complacency. Instead, it just suggests we need to take a closer look at productivity.

To increase productivity in a service, we need to tie it to a progressive sector. For example, online education could greatly increase productivity in the education sector by teaching to much greater numbers.5Bryan Caplan has argued that a large part of education is not actually learning stuff, but about signalling certain desirable qualities (intelligence, conscientiousness and conformity) to employers. Though I think Caplan overstates the signalling portion, I’m sure he’s right that it’s non-zero. Plus, there are other non-signalling, non-learning benefits that traditional education has over online education (e.g. making friends, having a socially acceptable excuse to delay working). These limit the size of potential productivity gains in education. In healthcare, better use of IT and AI could similarly help reduce costs by standardising records or automating diagnosis. The better capital is as a substitute for labour, the more the Baumol effect will disappear.

Another way to lower prices in healthcare and education is to increase the supply of skilled workers (thereby reducing the cost of skilled labour). Those workers don’t even have to be in education or healthcare, since skilled labour can substitute for each other.

We should neither ignore this difference [in productivity growth] nor make too much of it. For thousands of years there wasn’t much improvement in goods production, either, but that changed with the Industrial Revolution. We may be on the verge of a service revolution brought on by robots and artificial intelligence. Growth is always uneven.

Other Interesting Points

- People have been complaining about the healthcare crisis for ages. Consider this quote from the early 1970s:

The health care crisis is upon us. In response to soaring costs, a jumbled patchwork of insurance programs, and critical problems in delivering medical care, some kind of national health insurance has seemed in recent years to be an idea whose time has finally come in America.

- Slowing net productivity growth is inevitable as we move more resources from fast-growing sectors into the slower-growing services sectors. However, this is not necessarily a bad thing. Faster growth is only good if it increases consumer satisfaction. Moving resources from manufacturing to the service sector could increase consumer satisfaction even if it reduces productivity growth.

My Review of Why Are the Prices So D*mn High?

Why Are the Prices So D*mn High? was a revelation for me. Even though I’d heard of Baumol’s cost disease and the string quartet example before, I hadn’t really understood it that well. The book is free and short, at just 92 pages. I wouldn’t say it’s exactly easy to read for a lay audience, but it’s certainly more accessible than the typical economic paper.

I also appreciated that Alex Tabarrok published this even though he’s a Libertarian and some of their findings are inconvenient for the standard Libertarian complaints about government regulation causing high prices. While the book points out (quite reasonably) that the Baumol effect doesn’t preclude those complaints, overall Tabarrok shows himself to be someone who follows the evidence. (I have no idea where Helland’s political affiliations lie.)

I know some commentators have quibbled over the exact figures used and how much of the price increases in healthcare and education really are caused by government intervention, administrative bloat or something else. I’m not going to get into that here because I think they’re kind of secondary to the main point. Helland and Tabarrok don’t claim that Baumol drives everything, or that policy interventions to try and lower costs in this space are all futile.

As I see it, the main point is just that if you get uneven productivity growth in different sectors, prices in slower-growing sectors will rise relative to prices in faster-growing sectors, because all prices are relative. I think Tabarrok actually states this more clearly in a podcast promoting the book:

Here’s another way of thinking about why, even in a perfectly fantastic working economy, a healthy economy, some prices must rise — it’s because prices are opportunity costs. And all opportunity costs cannot fall. Sort of by definition, all opportunity costs cannot fall. So we have to see, so long as there’s some differential productivity, it has to be the case that some prices rise.

I just don’t see how that can be wrong.

Let me know what you think of my summary of Why Are the Prices So D*mn High? in the comments below!

Download Why Are the Prices So D*mn High? in PDF and epub

If you enjoyed this summary of Why Are the Prices So D*mn High?, you may also like:

- Book Summary: The Case Against Education by Bryan Caplan

- Book Summary: Economics: A User’s Guide by Ha-Joon Chang

- Book Summary: Thinking in Systems by Donella Meadows

- 1Though college subsidies exist, the costs are still mostly borne by students and their parents. Students have also been paying a larger share of education costs over time—between 2000 and 2015, the student share increased from 50% to nearly 75%.

- 2“Productivity” growth refers to increases in outputs that cannot be explained by increased inputs (increased capital, labour, energy, materials or services). Technological advancements that let us produce the same or more outputs with fewer inputs therefore increase productivity.

- 3While the rising cost of labour inputs is the best explanation for the rising cost of education, Helland and Tabarrok aren’t suggesting that teachers are overpaid. They think teachers are earning a relatively normal wage for their level of skill and education. (They earn about 5% more than similar workers in the private sector because of teachers’ unions. But unions can’t explain why teachers’ wages have increased over time—and they certainly can’t explain why faculty compensation has increased.)

- 4By “real income”, Helland and Tabarrok don’t just mean nominal income as adjusted for inflation. They mean the amount of stuff we can produce for the same amount of capital and labour hours.

- 5Bryan Caplan has argued that a large part of education is not actually learning stuff, but about signalling certain desirable qualities (intelligence, conscientiousness and conformity) to employers. Though I think Caplan overstates the signalling portion, I’m sure he’s right that it’s non-zero. Plus, there are other non-signalling, non-learning benefits that traditional education has over online education (e.g. making friends, having a socially acceptable excuse to delay working). These limit the size of potential productivity gains in education.

2 thoughts on “Book Summary: Why Are the Prices So D*mn High? by Eric Helland and Alex Tabarrok”

It’ll be interesting to see if the AI revolution (i.e. ChatGPT and it’s successors) will drive innovation and productivity in (most of) the service sector. Supposedly in such a scenario, by the argument of the Baumol effect, these sectors would not increase as much relative to the manufactured goods sectors.

However, I suppose AI might be similar to the computer revolution, in that all (most) sectors benefitted similarly from the new technology and hence we still saw the Baumol effect during the computer era we have just passed.

It’s a great question and your comparison with the computer revolution is apt. The other factor is that in addition to considering which sectors benefit more from the new technology, we may also need to look at which sectors rely more on labour (particularly skilled labour) to realise those benefits.

Even if the AI revolution lifts productivity in most of the service sector, some sectors (or even parts within a sector) will still be more reliant on labour than others. So I expect prices for basic professional services like law and accounting will fall, but prices for premium services that require meeting with a real human will go up.