What motivates people to go to war? In this summary of Why We Fight: The Roots of War and the Paths to Peace, I outline Chris Blattman’s five causes of wars. From those five causes, Blattman suggests four paths to peace.

Buy Why We Fight at: Amazon | Kobo (affiliate links)

Key Takeaways from Why We Fight

- War is rare.

- War is rare because war is ruinous. There is a “bargaining range” within which each party is better off than going to war, even if they expect to win that war, because of the costs that war imposes. Brief skirmishes are common, but cool heads usually prevail.

- Be aware of selection bias when trying to understand wars. Wars often follow hostility and competition, but there’s hostility and competition all the time. The vast, vast majority of the time it does not lead to war.

- There are broadly five reasons for war:

- Unchecked interests. Basically the principal/agent problem. The leaders who decide whether to go to war are not the same as the people who bear the costs of the war.

- Intangible values. Some intangibles like prestige, honour and glory can only be achieved through war. War can therefore “increase the size of the pie” to the extent people value these intangibles.

- Uncertainty. If opponents see their chances of success differently, they see different bargaining ranges. People have incentives to bluff and play hardball so that they get a bigger slice of any negotiated outcome. The presence of future rounds and multiple players can also increase these incentives.

- Commitment problems. If one side can’t trust that the other will keep to a negotiated outcome, they may prefer to go to war. A preventive war is the classic example. Commitment problems are also rife in civil wars, and explain why such wars tend to be longer and less likely to result in a negotiated peace.

- Misperceptions. Rationality sometimes fails. People can be overconfident about their chances of success. They may misconstrue the other sides’ actions and intentions. Group dynamics can sometimes make this worse and amplify individual biases.

- These five reasons compound. Each one narrows the bargaining range, but rarely eliminates it and causes a war by itself. But they can cumulate and, in combination, significantly narrow or even eliminate the bargaining range.

- The book suggests four paths to peace:

- Interdependence. Interdependence makes parties internalise some of the costs war would impose on the other side. This widens the bargaining range.

- Checks and balances. Distributing power between many groups can reduce all five reasons for war. Checks and balances doesn’t necessarily mean democracy – there are other ways in which power can be distributed.

- Rules and enforcement. These can deter bad behaviour and help groups cooperate by enabling credible commitments.

- Interventions. Examples include punishing, enforcing, facilitating, socialising and incentivising. They can work, but imperfectly, and it’s hard to measure how effective they are.

- But war is a wicked problem.

- Wicked problems have no easy solutions, various causes, multiple actors, and each case is slightly different. Solutions are not one-size-fits-all; they need to be tailored to the circumstances.

- Incrementalism is better than grand visions. With small steps, we can get feedback and learn as we go. We should embrace experimentation and trial and error.

- We also need to be patient and keep our expectations realistic. Change that happens over a couple of decades is already very fast. A century is more realistic.

Detailed Summary of Why We Fight

War is rare

What is war?

Blattman defines war as “any kind of prolonged, violent struggle between groups”:

- Prolonged. War is not just a brief skirmish. While short and deadly fights are important, Blattman wants to understand why opponents will spend years or decades destroying themselves and each other. Violent skirmishes are not unusual but they rarely escalate into a war. Cooler heads normally prevail and find a compromise.

- Groups. A lot of fights at the individual level are short-lived. Big groups are more deliberate and strategic. Those groups are not necessarily countries – they can also include villages, clans, gangs, religious sects, and ethnic groups.

- Violent. It’s normal for groups to compete fiercely against each other or be hostile towards each other. Competition and rivalry can even push people to innovate, grow and improve. That’s normal. Prolonged violence between groups, however, is not.

Beware of selection bias

It’s easy to forget that war is the exception, not the rule, because we don’t see the wars that don’t happen. This selection bias causes us to overestimate the frequency of war and misunderstand their causes.

Most of the usual alleged causes of war – such as flawed leaders, historic injustices, poverty, angry young men, cheap weapons, power shifts – are common. But war is not. For example, when conditions in Europe changed to favour the peasantry, some peasants rebelled against the elite. Usually the elites gave up some power to avert a revolt. Small groups of monarchs also met to carve up countries and continents without a war.

War is rare because war is ruinous

Each side usually tries to avoid war because war is ruinous. Since war destroys value, each side will almost always be better off with a peaceful compromise.

Blattman compares the spoils of war to a pie that can be divided in a negotiation:

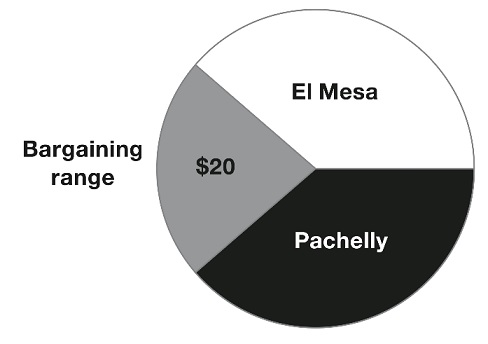

- Let’s say the pie is $100 to begin with. (The two sides in the diagram below are El Mesa and Pachelly, two criminal groups in Medellin.)

- Assume each side has a 50% chance of winning a war and getting the entire pie.

- If the act of war destroys $20 of the pie, there will only be $80 left for the victor.

- Each side then compares 50% chance of a $100 pie (if they negotiate) to 50% chance of an $80 pie (if they war). Negotiating clearly wins out over war.

- The $20 value that would be destroyed in war is the “bargaining range” within which each side can get a better outcome from a negotiated peace.

This model implies that we should expect peace even if:

- The costs of war are low. If costs are low, the bargaining range is smaller, but it still exists. Counterintuitively, this suggests that peace is more likely when costs are high and weapons are particularly destructive. New weapons discoveries affect the balance of power and how the pie is shared, but don’t necessarily cause war. History supports this – as weapons have grown more powerful, wars have become less frequent.

- There’s an imbalance of power. The weaker side should expect a smaller slice of the pie in a negotiation, but they will still be better off than going to war.

Five Reasons for Wars

The five reasons for war interrupt the pie-splitting process in different ways, by relaxing some of the assumptions in that model. The five reasons are:

- Unchecked interests;

- Intangible incentives;

- Uncertainty;

- Commitment problems; and

- Misperceptions.

Causes often cumulate to make peace more fragile, with each one reducing the bargaining range. It’s rare for a war to have just one of these causes. Each reason makes war more likely, but not inevitable.

It’s tempting to blame a war on an idiosyncratic event that most directly triggered it. In reality, these idiosyncratic events only spark a war when the underlying fundamentals have already narrowed the bargaining range. [See also Causality is so much harder than we normally think.]

Unchecked interests

The above pie-splitting model assumes each side is a united whole, with leaders trying to maximise the group’s collective interests. However, the people deciding whether or not to war may have a different set of risks and rewards from the group they (supposedly) represent. This is a form of the principal-agent problem in economics.

Leaders’ interests will never align perfectly with the group they represent. But remember that war is still rare. Even unchecked leaders stand to lose something from war because war is expensive and risky. So unchecked interests usually narrow the bargaining range without eliminating it. In extreme cases, it is possible for unchecked interests alone to eliminate the bargaining range, and maybe even invert it, thereby causing a war.

Governments have been highly centralised and unequal for most of human history, and therefore prone to war bias. However, while unchecked interests are clearest with god-kings and dictators, it can also arise in representative democracies (to a lesser degree). Elected officials’ interests will not always align with their citizens’ and accountability mechanisms may be weak.

Examples

- Countries in sub-Saharan Africa, such as Liberia, were decolonised very quickly. Power was left in the hands of a very small and unaccountable ruling class. Unchecked interests may partially explain why these countries are some of the most violent in the world.

- In The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli wrote of how a prince could use war to his advantage by privatising the benefits and socialising the costs.

- During the Cold War, the Soviet Union and the US fought proxy wars in other countries. The superpowers stood to gain an increased share of the global pie, without bearing most of the costs of these proxy wars. The people affected by the fighting had no way of holding the US or Soviet Union accountable.

- A study of Mexican labour court cases involving back pay compared the results of cases with government lawyers vs private lawyers. Government lawyers didn’t earn big fees and tended to give employees realistic assessments of their cases. Most of these ended up settling outside of court. Private lawyers earned high fees from lawsuits and were more likely to go to court – but they didn’t deliver better results.

- US legislators with draft-age sons were about a sixth less likely to support war and conscription than those with draft-age daughters. As soon as their sons passed the conscription age, these politicians’ support for fighting rose.

Example: American independence

Based on his writings and lifestyle, George Washington seemed to have been motivated at least in part by his desire for land and personal wealth. He had enormous land holdings, which were threatened by Britain. Some of his most valuable land claims were in the Ohio River Valley, which the British Crown had pledged to Canada. The Crown had also invalidated some of his other land holdings.

Like Washington, many elites who signed the Declaration of Independence had a lot to lose from British colonial policy. Most Americans at the time actually opposed a revolutionary war – but most Americans couldn’t vote back then.

Blattman acknowledges the American Revolution had many causes, including a noble ideology of self-determination. But the founding fathers, including Washington, also had economic incentives to go to war. When he died, Washington was the richest US president of all time. One ranking even has him as the 59th richest man in US history. [The reference for this seems to be from The Wealthy 100 by Michael Klepper and Robert Gunther.]

Blattman also notes that Washington was actually a relatively constrained leader. Power in America was widely distributed at the time, so he needed broad coalitions in order to act.

Intangible incentives

War can achieve intangibles such as glory, honour, revenge, ideologies, that can’t be won in a compromise. To the extent a leaders or groups value such intangibles, they will offset the costs of war and shrink the bargaining range.

In theory, such intangible incentives could eliminate the bargaining range but this is rare. But as noted above, the reasons can cumulate. For example, it is common for unchecked rulers to desire glory and status.

Blattman discusses three such intangible incentives:

- righteous outrage;

- ideologies; and

- glory and status.

Righteous outrage

Righteous outrage is a powerful social norm found in every human society. People want fairness and are willing to punish others to achieve it. Even monkeys seem to have a sense of fairness. The ultimatum game, possibly the most popular experiment in social science, provides evidence of this. Brain scanners have found that when a person rejects a split they consider “unfair”, the parts of the brain linked to emotional rewards lit up.

Many scholars think our sense of righteous outrage evolved to help us cooperate in large groups. Since small groups involve lots of repeated interactions, it’s harder to cheat. In larger groups, repeated interactions are much less likely and one-offs are more common. Rationally, there’s little incentive to punish cheating because you’re unlikely to deal with them again anyway. This poses a collective action problem. Our righteous outrage gives us an emotional reward when we punish cheating, which helps solve the collective action problem.

Similarly, fighting for a group poses a collective action problem as fighting entails personal risk. Righteous outrage at an outside attack motivates people to fight, solving the collection action problem.

Example: El Salvador Guerrilla Movement

In El Salvador during the 1980s, a guerrilla movement of peasants rose up against the land-owning elite. The guerrillas didn’t want to create a new land-owning elite, so were proposing that anyone could farm the land. So there was no economic incentive to join – you could just be a free-rider.

Elisabeth Wood interviewed hundreds of people and found that those who joined the movement had typically experienced terrible government repression in the past. Righteous outrage motivated them to fight.

Glory and status

Humans can be willing to go to extreme lengths for glory and status, even if it means risking their own lives.

For example, in WWII, the Luftwaffe (German air defence) motivated their fighter pilots with an elaborate system of medals and recognition. Just after a pilot was mentioned in the armed forces’ daily news, rivals in his unit worked harder to make more kills – and died faster as a result. The ordinary death rate for pilots was about 2.7% per month. After a colleague was mentioned in the news, the death rate increased by two-thirds. [Wow.] Over the course of the war, three-quarters of German fighter pilots were killed, wounded, or went missing.

Ideologies

Ideology can make compromise feel abhorrent, which makes war more likely. For example, many societies have waged war over religion.

Other examples:

- Adolf Hitler was motivated by his belief in the superiority of the German people. He wanted to conquer and “cleanse” the lands to Germany’s east, and compromise was not an option.

- Historians often blame the American Revolution on Americans’ ideology and unwilling to compromise (despite Blattman’s points about their founding fathers’ land holdings above).

Uncertainty

The two sides may not work on the same information. Even when both sides have the same information, they may assess the chances of success differently and therefore see different bargaining ranges. For example, the authors of Noise found that insurance risk assessors differed in their assessments of the same cases by around 50%. When two sides see different bargaining ranges, they can only compromise where their perceived bargaining ranges overlap.

Private information increases the risk of war. Sharing information can reduce those risks. Skirmishes are one way in which opponents reveal their strength. When there are future rounds and multiple players, reputation becomes important.

Private information increases risks of war

You know how strong you are, but the other side does not. This is private information. Private information increases the risk of war. When both sides have private information, the risk increases further.

Revealing information can help beliefs to converge and create a bargaining range.

Skirmishes are better at revealing strength than signals

Opponents may reveal information through posturing and signalling. But some signals are more credible than others. If you successfully bluff and pretend that you’re stronger than you are, you can get a better deal. But the other side knows you might be bluffing too so may call you on your bluff by attacking.

Actual fighting is a more credible show of strength. These skirmishes may actually prevent war as each side reveals its strength. Blattman thinks that uncertainty and disagreements about strength probably explains a lot of conflicts. Short-lived conflicts are much more common than prolonged war.

Reputation is important because of future rounds and multiple players

People may rationally refuse a deal that benefits them today so that they have a reputation for being “tough” and can get better deals in the future. For example, when there are more restive ethnic groups in a country, the government is more likely to fight or repress the first separatists to deter other groups.

Example – Iraq

Blattman believes reputation and private information is a big part of why the United States invaded Iraq.

We now know that Saddam’s regime could not develop weapons of mass destruction (WMD). But Saddam was careful to hide this information because knew he’d have greater bargaining power if he could threaten harm. He had one of the most secretive regimes in the world – even Iraq’s top generals weren’t sure what stockpiles the regime had. The US had very few diplomats and sources on the ground and only found out weeks before the invasion that Saddam had no WMDs.

It turns out the US wasn’t even one of Saddam’s top 3 threats. His biggest fear was an internal coup or popular revolt. Saddam was an uneducated, thuggish member of the Ba’ath party, and the party’s more educated and urbane members looked down on him. His next biggest threats were Iran and Israel. Saddam thought he could deter their attacks if they thought he had WMDs.

The US had also been sending mixed signals over their willingness to go to war. In 1991, it held back from invading Iraq. In 1993, it withdrew from Somalia. While it did intervene in Bosnia in 1995, it did so only reluctantly. Post-war interviews with Ba’athist officers suggest that Saddam thought the US would bomb Iraq but not march on it. The US was also concerned about its reputation – people thought its resolve was waning. So part of why it invaded Iraq was to send a signal to Iran and other countries seeking nuclear weapons.

Commitment problems

If you can’t trust that the other side will commit to a negotiated outcome, you’re less likely to agree to peace.

Preventive wars

A preventive war is an example of a commitment problem. You’d rather crush your rival now while you still can, so it can’t grow stronger than you. Even if your rival promises not to use their power once they grow strong, that promise would not be credible as you’d have no way of enforcing it. The classic example of a preventive war is the Peloponnesian War between Athens (the rising power) and Sparta (the ruling power). [See also my summary of Destined for War – Can America and China Escape Thucydides Trap].

Blattman thinks the requirements for a preventive war are:

- A large shift in power;

- The rivals must anticipate that shift; and

- The power shift must be hard to prevent.

But even with a large shift in power, there’s still a bargaining range, because war should shrink the future pie as well as today’s one.

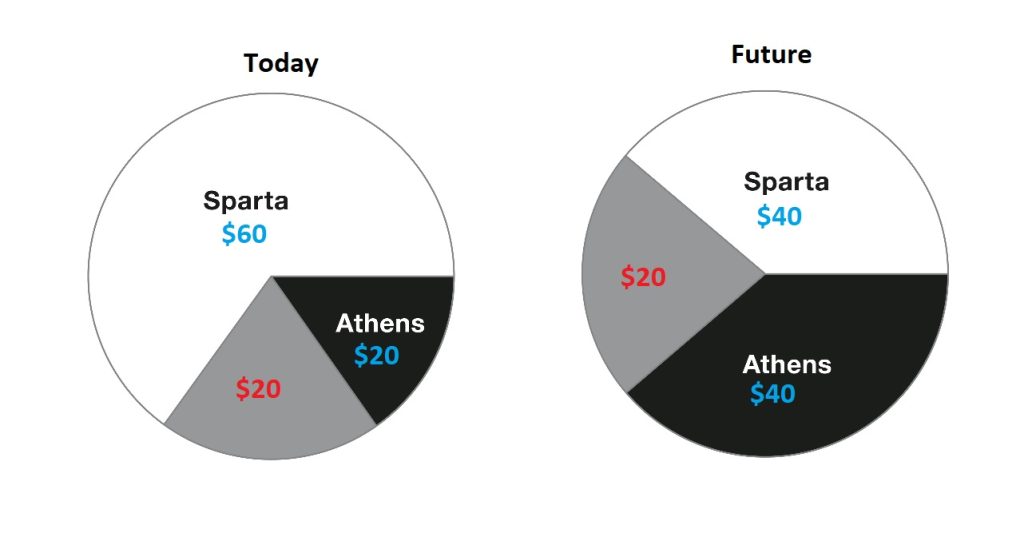

Take the example of Sparta and Athens. Assume Sparta currently has a 75:25 advantage over Athens today, which diminishes such that the two become evenly matched in the future. (Ignore time discounting for simplicity. It doesn’t affect the conclusion provided each side discounts the future by a similar amount. Discounting should in fact reduce the chance of war, by weighting today’s costs more heavily than future benefits.)

- Today’s pie is $100 pie, and the future pie is $100. So $200 in total.

- Assume war shrinks each pie by $20. Each war-damaged pie is now worth $80, or $160 in total.

- Sparta’s expected value of war today is 75% x $160 = $120.

- Athens’ expected value of war today is 25% x $160 = $40. (Its 50% chance of victory in the future is not relevant to its expected value of war today.) In the future, it can get a larger share of the pie – between $40 and $50, depending on whether the parties go to war. So Athens’ incentive will always be to wait and bide its time.

- Since Sparta’s odds get worse over time, it may prefer to go to war today. Sparta knows it can get at least $40 by going to war in the future, so Athens just has to give Sparta $80 today to make peace more attractive than war. Athens can offer at least $80 because its share of today’s remaining pie ($20) plus its expected share of the pie in the future (at least $40), is bigger than its expected value of war today ($40). [In fact, in this example, Athens would be better off even if it gave Sparta $99 of the pie today.]

Blattman thinks the reason Athens and Sparta went to war was because Sparta’s ally (Corinth) acted in ways that were pushing Corcyra, a strong, neutral power, towards Athens. If that happened, that big, sudden power shift could subordinate Sparta for good. This sudden, large power shift really created the commitment problem because it could eliminate the bargaining range. Under that future balance of power, Sparta may not be assured of getting anything more than $15. To match Sparta’s $120 expected value of war today, Athens would need to offer at least $105, which is larger than the entire pie!

In a footnote, Blattman explains how introducing a third player to this pie-splitting exercise creates multiple subgame perfect equilibria, some of which will include war. He draws parallels with unchecked leaders – it’s unlikely that Sparta’s ally, Corinth, took into account the costs for all Peloponnesian states before acting. More actors also introduce more noise, private information, and opportunities for bluffing. So a multipolar world of loose alliances may be less stable than a world with a few tight alliances. However, this is just a hypothesis as the research in this area is still developing.

Civil wars

Commitment problems are common in civil wars as the stronger side can often easily renege on any agreement. In international wars, countries can agree to stop fighting without the weaker party disarming or being subsumed by the victor, but this is less true for civil wars. Blattman thinks this is why civil wars tend to be longer than international wars (an average civil war lasts a decade) and negotiated settlements are rarer.

The decade or so after a war is particularly fragile, because that is when power is up for grabs. Both sides can grab more power if they act quickly, so neither can make a credible commitment. It’s like a handgun lying between two enemies. This is why civil wars often start and stop and start again. At the same time, institutions and trust are still weak.

Other examples of commitment problems

- World War I. Russia was a rising power, and Germany believed they had a limited window to act. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand gave the Germans an excuse to support Austria-Hungary in declaring war on Serbia (Russia’s ally). They hoped that Britain would not join in, or at least join late.

- US invasion of Iraq. The US’s main concern was that even if Saddam didn’t have atomic weapons in 2003, he couldn’t commit to giving them up. On the flipside, Saddam’s fear was that if the US knew he didn’t have WMDs, they could use that information to incite a rebellion or support a coup. The US could not commit not to do this.

Misperceptions

To reach a bargain, each side has to estimate their chances of success and predict how their rivals will respond. Misperceptions make it harder to find a deal. Blattman focuses in particular on:

- Overconfidence;

- Misprojections and misconstruals; and

- Group dynamics.

Overconfidence

We tend to overestimate our own abilities and underestimate uncertainty. [The Shock Test is a nice little exercise that illustrates the latter.] Funnily enough, in a survey of a million high school students, one quarter of them put themselves in the top 1% for getting along with others. There is some lab-based evidence to suggest that men are more susceptible to overconfidence than women. Men were also more likely to attack in war simulation games. Even when people know of this bias, they tend to think themselves somehow immune.

However, overconfidence doesn’t always lead to war. Both sides usually understand that there is uncertainty so if their opponent’s demands look unreasonable, they should reconsider their beliefs and look for more information. As mentioned above, skirmishes are a way to test strength and get more information.

Misprojections and misconstruals

We unconsciously assume that others think the same way we do and have the same information we have. There are many variations of this: the curse of knowledge (when you forget what others don’t know); hindsight bias (thinking something was obvious, only with the benefit of hindsight); false consensus (assuming others would make the same decisions as you); and the lens problem (assuming others are like you).

There’s also attribution bias (attributing others’ actions to their character rather than the situation). We tend to blame the situation when members of our in-group err, and blame the person when members of our out-group do the same.

Biases don’t just result in erroneous beliefs. They can also stir up anger and other passions, which can exacerbate misperceptions and make people act less rationally. Over time, violent overreactions can poison the relationship between two sides and significantly narrow the bargaining range.

Group dynamics

Organisational dynamics are important to understanding war because decisions are made in groups. Even autocratic regimes usually make important decisions in small groups.

Groups perform better than individuals for many types of decisions, particularly those that have a clear right or wrong answer. However, it’s less clear if groups perform better for subjective questions in uncertain environments:

- Groups can amplify our individual biases. Like-minded group members tend to get more extreme in their views after deliberating. Evidence also shows that group decisions gets worse when members share a social identity.

- Information possessed by individual members does not always get aggregated. Some members may censor themselves. Groups also tend to focus on information that they all share, rather than information that’s only partially shared, even if the latter is more pertinent.

Groups tend to get better at aggregating and reviewing information if the group discussion is longer, there are formal processes for sharing and reviewing information, and there are norms of accuracy, problem-solving and critical thinking.

Big bureaucracies often have systems to acquire information from multiple sources and to try to overcome some of our automatic biases. Their decisions are therefore often more rational and less biased than a small group’s.

However, this is not always the case. Some large organisations have systems and cultures that discourage information gathering and dissent. Big bureaucracies also suffer from a lack of organisational attention and memory. For example, before the Troubles in Northern Ireland began, the British Parliament spent less than 2 hours each year discussing the province. Even now, the UK secretaries of state are not that familiar with the place when they first come into the role.

Other explanations for war and peace

Blattman addresses some other commonly proffered explanations for war or solutions for peace, such as poverty or that humans are naturally aggressive.

Humans are naturally aggressive and violent

For example, there are many firsthand accounts of rioters, soldiers, and football fans thoroughly enjoying and even seeking out violence. Such violence can strengthen social bonds and give people meaning and a sense of identity.

However, Blattman doesn’t think we can extrapolate from these small-scale instances of violence to wars. Wars are much longer, more exhausting and costlier, and require groups to coordinate and plan for weeks or months on end.

Men are more aggressive

Many people think that if women were in charge, there’d be less war. While Blattman accepts that there is evidence to show that men are more aggressive at the individual or small group level, most of that is reactive and situational.

Researchers looking at 120 years of data on world leaders have found that countries led by women are about as likely to start a war as any other. There may be a selection problem, though. Women face more hurdles to become leaders so those who make it may be more war-biased than the average woman. Also, women leaders tend to come from democracies which are checked and balanced by parliaments and bureaucracies full of men. The results may be different if we looked at unchecked female leaders, or if women were well-represented at all levels of decision-making.

Oeindrila Dube looked at data from early modern Europe, where an unusual number of monarchs were women and some of this was due to random birth order. She found that queens were almost 40% more likely to be at war than kings. One reason was that other rulers saw queens as weak, so were more likely to attack. But Dube also found that when queens got married, they showed aggression towards nearby states, which was a bit puzzling. In any case, the number of queenly reigns is small enough that it’s hard to draw firm conclusions.

Parochialism

Humans are quick to form identity groups and tribes, and favour members in their in-group over the out-group. Such parochialism can reduce the likelihood of war because it makes us care about the costs of war on members of our in-group.

Some argue that parochialism goes further and makes us take pleasure in the out-group’s pain (schadenfreude). If true, this would be an intangible incentive for war. Blattman says the evidence on out-group antipathy is mixed. There’s some evidence of it in the lab but it’s not clear how that translates to real life.

However, parochialism, antipathy and aggression can be used and fed by leaders who want to go to war. For example, in Rwanda in 1994, Hutu extremists killed more than 70% of the minority Tutsi population. A popular radio station broadcasted propaganda that encourage Hutus to join in the genocide. Far more Tutsis were killed in the villages with radio signals.

Poverty

Commodity prices can be very volatile. Countries with volatile commodities have not done as well over time, but this volatility did not seem to extend to more conflicts or wars.

Blattman thinks poverty can explain why wars intensify, but not why they start in the first place. Going back to the “pie” model – even if poverty causes the pie to shrink, war is still ruinous, and parties would still be better off negotiating a peace.

(In a footnote, however, Blattman clarifies that it’s surprisingly hard to distinguish between war breaking out and a war intensifying. He also points to some contrary evidence by other researchers in a separate footnote.)

Four Paths to Peace

The path to peace involves addressing the fundamental five reasons for war. Blattman suggests four paths to peace:

- Interdependence;

- Checks and balances;

- Rules and enforcement; and

- Interventions.

Staying peaceful doesn’t necessarily mean things are great. Rivalries may still be intense and hostile, without erupting into war.

Peace is not the absence of conflict, it is the ability to handle conflict by peaceful means.

Nor does peace mean equality or justice. The side with more bargaining power tends to get a bigger share of the pie in any negotiated outcome.

Interdependence

Interdependence makes peace more likely because anything that hurts or destroys one side will negatively affect the other side. It makes each side internalise some of the costs to the other side. This raises the costs of war and increases the size of the bargaining range but does not eliminate the risk of war.

Economic interdependence

There aren’t any good natural experiments to prove this at the international level, but there is some evidence within countries. For example, there is conflict in India between Muslims and Hindus. But in some Indian coastal cities such as Somnath, Muslims and Hindus have been socially and economically integrated for hundreds of years. Saumitra Jha, an economist, found that sectarian violence was about five times less than in similar coastal towns. These cities also tended to punish, rather than reward, belligerent leaders in elections.

Another way of framing this is that war is more likely when parties are not economically interdependent. For example, countries rich in oil have less incentive to find peace. Moreover, oil tends to fuel authoritarianism because it’s confined to a relatively space and therefore easy to monopolise and control. [There’s a lot of work on this related “resource curse” phenomenon.]

Social interdependence

Social interdependence similarly increases peace. Historically, many societies have married their daughters to the sons of their enemies. Adam Smith, in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, thought that one reason commerce would increase peace was because it would extend our circle of sympathy to those we trade with.

There is mixed evidence as to whether social interaction by itself is enough.

- Some evidence involving young people shows that bringing members of antagonistic groups together in schools, sports clubs, etc has reduced discrimination.

- However, there is some contrary evidence from Indonesia. The government relocated 2 million volunteers from Java and Bali to various villages in the outer islands. Some villages were more mixed than others, providing a sort of natural experiment. Villages settled by lots of ethnic groups experienced greater trust, interethnic marriage and community engagement. On the other hand, in villages settled by very few groups, the groups became more polarised and antagonistic.

Blattman thinks that polarisation reduces when group identities overlap. For example, a Muslim and a Christian may find common ground if they share an identity as a “soccer fan”.

But if identities don’t overlap and instead line up and reinforce each other, that can exacerbate rather than reduce group divisions. For example, Uganda is highly polarised and the Acholi and Ankole ethnic groups have very few identities in common.

Mali’s joking kinship system

Group identities can change over time, and can even be manipulated by others. Hundreds of years ago, Sundiata Keita, who founded the Mali empire, joined different groups together through their surnames. The system is today called a joking kinship or “cousinage”. A person named Keita is considered a “cousin” of someone named Coulibaly, and that informal relationship would give them the right to tease each other using a standard set of jokes.

Even though it’s based on this completely arbitrary and fabricated identity, the system still pacifies politics in Mali to this day. People are just as likely to vote for someone with a cousinage name as they are to vote for someone with their own name.

Checks and balances

What are “checks and balances”

By “checks and balances”, Blattman is talking about polycentric governance rather than necessarily “democracy”. Polycentric governance is where power is distributed among many centres, making it hard for one group to impose its will on the rest. For example, China is polycentric in many ways even though it is not democratic.

Polycentric governance can include:

- Separation of powers between the executive, legislature and judiciary;

- Local and regional authorities having power to tax, spend and regulate;

- Bureaucrats acting as a source of continuity and counterbalance to party politics;

- Power pushed up to supranational organisations and regulated by treaties; and

- Organisations outside the government that lobby, organise and protest.

In addition, de facto power may be concentrated or dispersed:

- Military. America for example has made its military polycentric by dividing it into many branches.

- Mobilisational. Things like media and churches have power to mobilise masses.

- Material. Wealth and means of production may be owned by many or a few.

How we deploy foreign aid can have a huge impact on power. Aid that promotes distributed development (building schools and road, community grants, etc) probably increases de facto power. In contrast, funnelling aid through the central government probably reduces polycentrism and makes the world a bit less stable.

Why checks and balances prevent wars

Checks and balances reduce the risk of war because:

- Power is held to account by those beside and below them, so leaders have to internalise more of the costs of fighting (addressing unchecked interests).

- They reduce the ability of leaders to seek personal glory and vengeance (addressing intangible incentives).

- Checked governments tend to be more transparent (addressing uncertainty).

- Institutionalised decision-making could mitigate leaders’ biases and errors (addressing misperceptions).

- Separation of powers and other institutions can help leaders make credible promises (addressing commitment problems). [Interesting. It depends on the institution though. The doctrine of continuing parliamentary sovereignty probably worsens rather than alleviates commitment problems.]

Obstacles to polycentrism

In the real world, polycentrism can be hard to achieve:

- Peacebuilders tend to empower the centre. International organisations often can’t deal with regional governments or villages unless the centre agrees.

- The centre also tends to hoard power. Few politicians, even well-intentioned ones, are willing to give away power to their people whose policies they disagree with.

Blattman, however, points out that checks and balances can actually empower the centre in the longer term. People are more willing to hand over power if they know the government is constrained and limited than if it is unfettered.

Rules and enforcement

Institutions that provide rules and enforcement reduce the risk of war. These can take many forms. Even rudimentary institutions can provide rules and enforcement. For example, early states operated much like the criminal organisations, razones, in Medellin. They tended to be unequal and repressive, but were more peaceful than no order at all. One way in which they promote peace is by helping rivals make credible commitments.

Societies without formal institutions can still have norms and cultures that help keep peace. Examples include religious edicts, taboos, and the culture of honour. The promise of retribution acts as a deterrent, so people hesitate to harm each other.

The international system is quasi-anarchic as there is no world government. But there is still some order:

- Countries form hierarchical alliances led by the strongest states. Each hegemon keeps the peace within its alliance and negotiates with other hegemons on behalf of the group. Although the hegemon may subdue other nations through force, these relationships can still be mutually beneficial. Subordinate countries may defer to or support the hegemon on certain policies, and in exchange they may enjoy security without having to spend as much on their own defence.

- International institutions, like the UN and League of Nations, also have a role in setting and enforcing rules. Enforcement is not perfect and cannot fully constrain the most powerful countries, but it’s better than nothing.

Interventions

Interventions may take various forms: punishing; enforcing; facilitating; socialising and incentivising. They sound great in theory but are harder to do in practice and less effective than we may like. But war is a wicked problem (see further below) and we shouldn’t expect these interventions to work magic. They can still be useful.

Punishing

Most societies have some system of rules and penalties to deter people from doing bad things.

States have long used foreign sanctions against each other. Broad-based sanctions may hurt many innocent people without hurting the rulers at the top. For example, trade sanctions against Iraq in the 1990s shrank the economy by half while Saddam Hussein just grew wealthier. In fact, the sanctions caused his power to increase, as he could control the scarce sources of food, currency and supplies. In contrast, targeted sanctions are aimed at particular leaders and their cabals, but the difficulty with these is finding the right people.

Sanctions seem to be moderately effective. Researchers have found about a third succeed, depending on how you measure success. It’s hard to measure because of the selection problem – we tend to see only cases when sanctions have been used, rather than cases where the threat of sanctions effectively deterred behaviour. Blattman concludes thinks targeted penalties are more of a persuasive idea with some imperfect evidence, rather than a proven strategy.

Enforcing

Organisations can intervene by enforcing rules and helping to uphold bargains.

Blattman discusses UN peacekeeping missions, which tend to be polarising. Rich countries don’t want to put their troops in danger so outsource peacekeeping to poor and middle-income countries. Those countries make a lot of money from peacekeeping, but their troops tend to be poor, uneducated and badly managed. They also tend to have a lot of sex with local women for money. Blattman’s colleagues interviewed a random sample of women aged 18-30 in Monrovia and found that three-quarters of the women said they’d had sex for money or gifts with someone from the UN!

While Blattman believes peacekeeping missions could work much better, he still thinks they increase the chances of peace. He spoke of one mission from Pakistan that he came across while in Liberia. The soldiers could not speak English so could not interact with the Liberians. But when an ethnic riot did break out, they were able to clear the rioters easily, since the rioters were unarmed and disorganised. This may well have prevented the riot from escalating. Peacekeeping missions also build relationships with local leaders, help enforce bargains, and just calm things down.

Page Fortna, a political scientist at Columbia, compared wars that did and didn’t receive peacekeeping troops. She found that those who did had more lasting peace. In addition, there were signs that peacekeepers got sent to the more difficult conflicts on average, so their effectiveness may be even stronger than what a simple comparison would show.

Facilitating

Insurgents and terrorists tend to live in bubbles, in hiding or underground, completely ignorant of the outside world. Mediators can help foster trust and reduce uncertainty, private information, and misperceptions.

A reputable mediator can help broker a peace by vouching for the credibility of one side. For example, in the mid-1970s, Henry Kissinger told Israeli’s prime minister that he believed the Egyptian president genuinely wanted peace. The two countries reached a peace agreement in 1979.

James Ballah rolled out a dispute resolution training program to local chiefs and other leaders in Liberia. Dispute resolution specialists visited around 100 out of 250 identified villages and ran workshops every few weeks. They taught basic negotiation techniques including active listening and mirroring, educated villagers about cognitive biases, and shared techniques to manage their anger and calm down. They found that, after a year or two, a third more disputes got resolved and violence fell by a third in the villages with these workshops compared to the villages without.

Socialising

Socialising, also known as civilising, is when a society develops norms of self-control, rationality, and concern for others, which lead to a decline in violence.

Some of these socialising skills and norms are taught explicitly – in pre-school or by village elders. Messages promoting social harmony can also be seen in our media and propaganda, such as Sesame Street. Authorities in Rwanda broadcast soap operas and talk shows promoting peace.

A microcosm of this socialising process can be seen in a program called Sustainable Transformation of Youth in Liberia (STYL). The program involved lots of standard cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) techniques, such as learning to cope with angry emotions and practising seeing the other side’s view. It was based on a program developed by a guy called Johnson Borh. Blattman and Borh later launched a randomised controlled trial with a thousand troubled men in the city. They found that asaults and criminality for men who had been through the program dropped by half – both a year later and even ten years later! Results were strongest among men who also got some cash to start a small business on the side, even though those businesses usually failed.

Incentivising

The darker side of peace involves using carrots to get the people with power not to fight. This may involve buying them off with a larger share of aid, resource rents, or political seats. Rich countries give foreign aid even when they know it will just benefit the rulers, if they think it’s worth it to avoid war.

There is a tough trade-off here against “checks and balances”, because centralising power and allowing it operate unaccountably increases the risk of each of the five reasons for war. In the short run, incentivising may the only way to avoid war but in the longer run, you want power to be shared more broadly. It’s a delicate balance between realpolitik and idealism.

War is a wicked problem

War is a wicked problem. “Wicked” is actually a technical term to describe complex social problems that are difficult to solve. They have many possible causes, success is hard to measure, multiple actors are involved, and each case is different. Poverty and drug abuse are other examples of wicked problems. Contrast such problems with smallpox, which had a clear cause, was well-understood, and had a solution (a vaccine) that worked in every case.

Don’t oversimplify and understand local conditions and power dynamics

International agencies often recommend broadly the same reforms for radically different countries, without regard to the local context. People also overlook actual power dynamics and come up with “optimal” solutions that don’t work, particularly when they’re not familiar with the country. No program is apolitical; everything affects the balance of power.

For example, cows are the main form of wealth in Lesotho, but cows can die during droughts so people lose their savings. One development project tried to help people sell their cows by providing infrastructure and access to markets. But the problem was that Lesotho men didn’t want their cows to be sold. The men worked far away in in South African mines and deliberately bought cows back home because they didn’t want their wives spending it. The men who had the power therefore actively worked against the project, and it failed spectacularly.

Another example is when countries start writing constitutions following a conflict. Often they just copy another country’s constitution without any national discussion. Such constitutions may provide for a ritual of elections and democracy without resolving the fundamental question of how power should be shared.

Aim for small, incremental improvements and learn as you go

Outsiders and elites can still play an important role, but they need to approach the problem with humility. Instead of thinking of peace as a problem we can solve (e.g. “world peace”), we should aim for a slightly more peaceful world. Karl Popper wrote of a “piecemeal engineer” who knows how little he knows. He makes small, incremental reforms, carefully comparing actual results with expected results, learning along the way. It’s a structured, iterative, trial-and-error process. In contrast, large, sweeping reforms make it difficult to disentangle cause and effect.

Experiment and promote competition

Besides promoting peace, polycentric decision-making allows for experimentation and competition. For example, a federalist system allows provinces and states to experiment with different laws around minimum wages, taxes, etc. and learn what works through that process.

But a lot of peacebuilders don’t like to distribute power and complain about other organisations copying their ideas or competing for “their” donors. People also tend to be intolerant of failures, even though it is inherent in “trial-and-error“.

Be patient and realistic

Change happens slowly. Most people view Afghanistan, Iraq and Liberia as failed attempts at building capable states. But they were never going to become high-functioning states in just a few decades. It would have been amazing if they got there in even a hundred years.

Andrews, Pritchett and Woolcock looked at data on different countries’ capabilities in terms of having effective public services, a rule of law, capable bureaucracy and being relatively free of corruption. Afghanistan and Liberia were at the bottom. Guatemala was not quite at the bottom but somewhere near the bottom quartile. In a best case scenario where Guatemala somehow grew its capability as fast as the top 10% of countries, ever, it would only pass the midpoint of the list in about 50 years. If Afghanistan and Liberia performed at the same rate over the same timeframe, they would reach where Guatemala is now.

We also need to be realistic about our goals. Voters in the poorest states expect their governments to run primary schools, build health clinics, and rebuild roads. International donors similarly expect them to cut poverty, malnutrition and corruption in unrealistic timeframes. But these states simply don’t have the capability. For example, the Ministry of Finance for South Sudan in 2008 was a single guy in a trailer, yet people kept expecting him to do everything a Ministry of Finance normally does.

The state is human too. It’s some normal bloke or woman doing a job, being worried, trying to get promoted, et cetera – with imperfect information and imperfect judgment.u003cbru003e

If expectations are unrealistic, we risk labelling successes as failures and removing the incentive to improve. Moreover, when governments are weak, they should focus on things that only they can do, like establishing a functioning justice system. Non-profits can build health clinics and schools.

Other Interesting Points

- The bargaining range/pie-splitting ideas were initially applied to other conflicts like labour strikes and court cases. Thomas Schelling started applying insights from those areas to wars and Jim Fearon later developed the pie-splitting example.

- Blattman uses Medellín’s gangs, or combos, as an example throughout the book.

- The combos have various profit-making ventures in neighbourhoods they control, such as selling drugs and running protection rackets. Most of the gang leaders are in the Bellavista prison and run the city from within it (it’s a pretty lax prison where inmates dress in their own clothes).

- Though there are gang wars in Medellín, thousands more wars are averted through negotiations and trade. The region’s homicide rate is actually lower than in many big American cities.

- According to Thomas R Martin (2013), the Spartans’ declining fertility rate shrunk their population so much that they became inconsequential in international affairs by the later fourth century BC. This is an example of how important demography is to history.

- Surveys of Africans have have shown that, after a football match in which their national team won, people identified more strongly with their national identity and less with their ethnicity. There was no effect when their team lost.

- Authoritarian regimes sometimes hold fixed elections or allow public dissent that they then censor. One reason they do this is to get information about what people want so can then adjust accordingly, reducing the risk of revolution.

- The US founding fathers did not have much faith that voters would be able to consistently elect good leaders and wanted to protect against future tyrants. The president was initially a ceremonial role. (They chose the word “president” to mean that he would only preside over the legislature.)

My Thoughts

Why We Fight appears to be credible and well-researched, and Blattman backs up his assertions with detailed references. Blattman is generally fair and balanced. He admits when something is merely a hypothesis and when evidence exists to contradict his theory (although some of this is buried in the footnotes, which are quite extensive). But Blattman doesn’t sit on the fence too much, either. He makes his key points clearly and his arguments are compelling.

Blattman’s writing style is simple and clear. The book tackles a difficult and important problem and explains it in an accessible way with many examples. In my opinion, the first half of the book (examining why we fight) was much tighter than the second half (paths to peace). Like many books about “wicked” problems (such as Evicted), Why We Fight is much better at identifying the problem than at explaining how to solve it. Blattman makes a better attempt than most, and he openly acknowledges that in many cases it’s a tough trade-off and that he doesn’t have all the answers.

My main issues with the second half were:

- The structure. In particular, I think Blattman used too many lists. Five reasons for war was fine. Four paths to peace would have been okay, too. But the last path (interventions), consisted of five different measures! It’s like when you approach what looks like the top of the mountain, only to see that the peak is much higher than you thought. And after those five interventions, he gives us 10 more “peacemeal” commandments. (I simplified and grouped them together above, mostly under “War is a wicked problem”.) Overall, the structure for all the “peace” parts could have definitely been improved.

- Too ambitious. Since war is such a wicked problem, the solutions could have easily made up a separate book. Blattman seems to have bitten off more than he could chew by trying to go into any detail here and the book should have deliberately stayed higher-level. After all, Blattman’s suggestions to be humble, realistic, incremental, etc are pretty high-level themselves and he doesn’t offer a lot in the way of concrete solutions. If he’d taken that approach, he could have shortened the second half significantly.

That being said, I don’t mean to be overly critical of the book. I always enjoy seeing economic concepts being applied to other domains, and Blattman was generally a careful and thoughtful writer. I feel like he’s the kind of writer that wrote a book because he had an important point he wanted to make, rather than because he wanted to sell a book. (Apparently he also used to be a rock climbing instructor, which makes me a little irrationally biased in his favour.)

Buy Why We Fight at: Amazon | Kobo <– These are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase. I’d be grateful if you considered supporting the site in this way! 🙂

Have you read Why We Fight? If so, share your thoughts in the comments below! If you liked this book or summary, you may also enjoy my summaries of:

3 thoughts on “Book Summary: Why We Fight by Chris Blattman”

Thank you for this informative and useful summary.

As you said, it seems the author did a good job of describing the problem, and used many different examples to back up his points.

The part about whether gender affects the motivation to go to war was interesting. Wish there had been a larger sample of queen-led societies!

I also thought the point about more costly and more powerful weapons being a war deterrent was interesting.

By the way, I am not sure if we get notifications of any responses to comments. Could this be built in?

Thanks for your comment! Yeah, I found the gender stuff interesting as well, though it was a relatively small part of the book. I’m not sure that I buy his argument that, although studies have shown men are more aggressive, that’s just in individual and reactive contexts and doesn’t translate to being more war-prone (at least a little). But I take his point that what little research we have of queen-led societies doesn’t support the idea that men are more war-prone.

I think the gender question is more complex than just the differences in aggression, though. There are other ways in which men and women leaders may be different. Perhaps men are more likely to value honour, glory or vengeance highly, so may be more war-prone in that respect. However, one might equally argue that men are perhaps more rational, so are more likely to agree to a peaceful bargain. There may also be gender differences in terms of men and women’s circles of sympathy.

Overall, it makes sense that Blattman didn’t focus too much on this question because, while it’s interesting, the evidence is so weak that all we can really do is speculate. It doesn’t really suggest much for how to avoid war.

And thanks for pointing that out about the comment replies. I’ve just installed a plugin that should allow that now (weirdly, it doesn’t seem to be a default WordPress feature). You probably won’t get a notification for this comment though because I think you have to check the box before posting your comment.

Thanks!