[Estimated time: 10 mins]

The unusually good pictures in this post were all drawn by my very talented friend James. You can find more of his drawings at Non-Zero-Sum Games, where he writes about game theory, economics, philosophy, AI and more!

We usually assume that increasing productivity will make us better off. Broadly, I think that’s true. Countries that are more productive are richer, and richer countries tend to do better on many other indicators of well-being, such as health, education, and food security.

However, our happiness depends on multiple things, and some of these may be subject to zero-sum competition. In this case, generalised productivity improvements may not make us better off. Productivity gains will save us resources, but if we just spend those resources competing harder in zero-sum competitions, we won’t be any happier.

This post looks at whether zero-sum competitions might be preventing us from unlocking the full benefits of productivity gains. It has three parts:

- The first part defines “productivity” and explains why I think increasing productivity is generally good.

- The second part looks at what we need to be happy.

- Lastly, I explain how zero-sum competitions over things like status and land might negate some of the benefits of productivity gains.

In my second post over at Non-Zero-Sum Games, I look at how we might be able to extract ourselves from zero-sum competitions. Doing this would allow us to more fully enjoy our productivity gains.

Productivity gains let us produce more with less

The term “productivity” is often misunderstood. As I’ve said before, increasing productivity does not mean “making more stuff”. When economists talk about increasing productivity, they mean making the same amount of stuff with fewer resources. Those resources might include time, energy, capital or natural resources. In that case, provided you’re producing something that is net good (so not, like, superviruses or animal suffering), increasing productivity will almost always be good.

Of course, since you’re using fewer resources to make stuff you might then choose to scale up production—that is, make more stuff with the same amount of resources. But you don’t have to. You could just keep making and consuming the same amount, and just enjoy the resources you’ve saved from increasing productivity. So productivity improvements could, in theory, allow us to conserve natural resources without sacrificing consumption and give us more time for leisure and sleep.

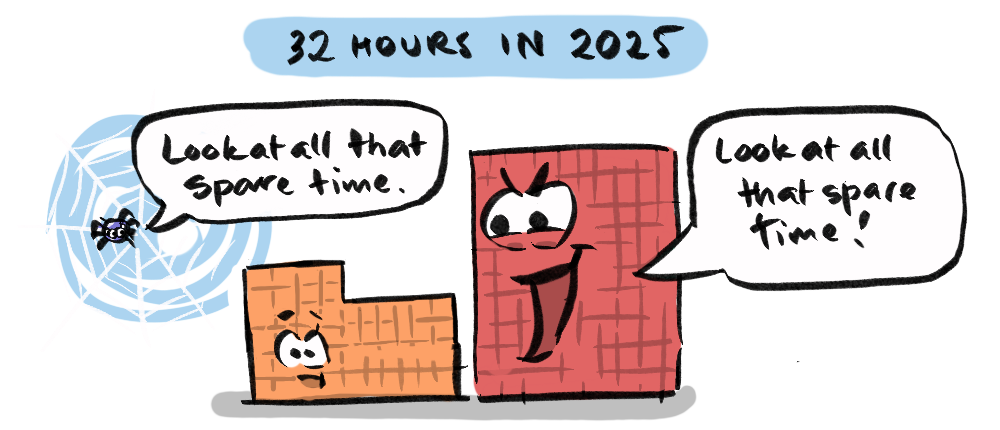

In an essay called “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren”, John Maynard Keynes surmised that if productivity kept rising, most people could be working just 15 hours per week by 2030, while enjoying a standard of life 4 to 8 times higher than when Keynes was writing in 1930. Our problem would then be how to spend all our leisure time.

We’re now in 2025. Keynes’ prediction that the standard of life would increase by 4 to 8 times has proven remarkably accurate.1“Standard of life” as measured by real GDP per person. See Beretta et al (2024) and Crafts (2022). Yet it’s safe to say his prediction about our working hours will not come to pass. So why not?

To answer why we’re not yet working 15-hour weeks, we must look at what all our work is for. What do we need to be happy? This will then help us understand how increasing productivity can make us better off—and when it will fail to do so.

What makes us happy?

Happiness depends on multiple things. In 1943, Abraham Maslow tried to capture what humans needed to thrive and came up with the following hierarchy of needs:

- physiological needs — food, water, shelter, rest

- safety — security of body and resources

- love and belonging — intimate relationships, friends

- esteem — prestige, status, confidence

- cognitive — books, learning

- aesthetic — beauty, art

- self-actualisation — meaning and purpose

- transcendence — spiritual needs

Some of these needs are met by standard, rivalrous goods. Food is rivalrous because if I eat a burger, you can’t eat that same burger, so people end up competing over food. Luckily, the food supply is not fixed. Thanks to increases in agricultural productivity, we can produce food today with far fewer resources than we did a century ago. Productivity has therefore significantly relaxed the competition for food, particularly within developed countries.

Some of the other needs in Maslow’s hierarchy are non-rivalrous, meaning they aren’t subject to the ordinary laws of scarcity. When I get more rest, it doesn’t take away from your ability to rest. You becoming more self-actualised in no way takes away from my ability to self-actualise. The primary way in which productivity can help us meet these needs is by giving us more time.

This post focuses on our needs for status and land. Status is one of our “esteem” needs, but can also impact our need for “love and belonging”. Land affects our physiological need for “shelter” as well as “safety”. Both status and land are rivalrous, meaning we compete over them. However, unlike food, the supply for both status and land is relatively fixed.2My second post takes a closer look at how fixed the supply actually is, especially for land. And when supply is fixed, competition becomes zero-sum.

Note: Status isn’t necessarily bad

To be clear, even though the supply of status may be fixed, that doesn’t mean the existence of status is bad. Competing for status could still benefit society if it incentivises pro-social behaviour like helping others or inventing useful things over anti-social behaviour like cheating or beating people up. Whether or not competition for status actually does this is debatable.

For the purposes of this post, I’m just pointing out that to the extent that our individual happiness depends on status, it’s a zero-sum competition.

How zero-sum games can negate productivity gains

While productivity has increased a lot over the last hundred years, those increases have occurred unevenly across the economy. Manufacturing has seen substantial productivity gains, so standard goods like food, clothing and home appliances have gotten much cheaper. This is great!

However, there’s a limit to how happy these goods can make us because of diminishing returns. Going from “no food” to “some food” will make you much happier than going from “some food” to “so much food I really need to stop overeating”.

Okay, so we can’t become happier by consuming ever-larger quantities of standard goods. Still, increasing productivity means we won’t have to use as much time and energy to produce those goods. So can’t we enjoy all that extra time for rest and self-actualisation?

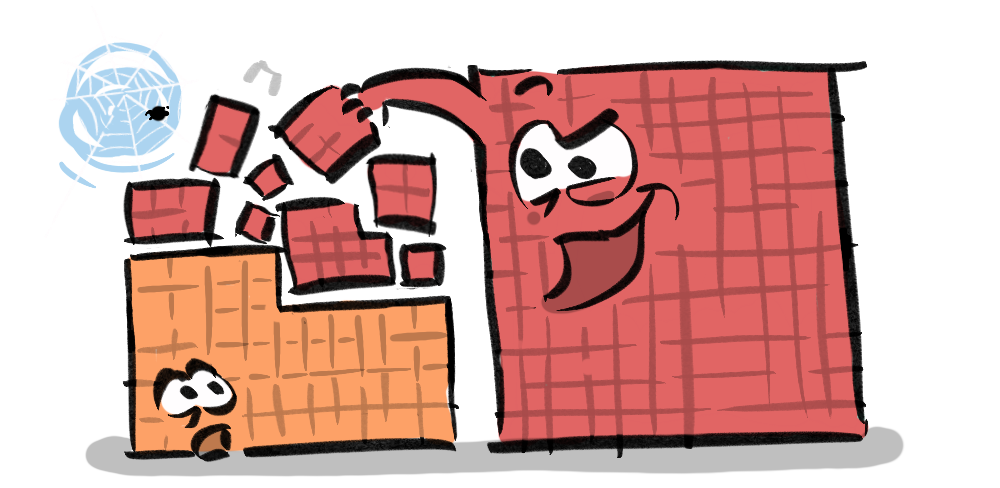

Not quite. The problem is that resources we save from productivity improvements in one area may just get diverted to another. And if that “other area” is a zero-sum game, we’ll be no better off. This may be clearer with an example:

Example: Productivity gains with zero-sum competition

Let’s assume that a hundred years ago, working a 40-hour week got you exactly:

- 20 units of standard goods like food, clothing, and home appliances.

- 20 units of housing.

Each labour hour in 1925 therefore gave you 1 unit of either standard goods or housing.

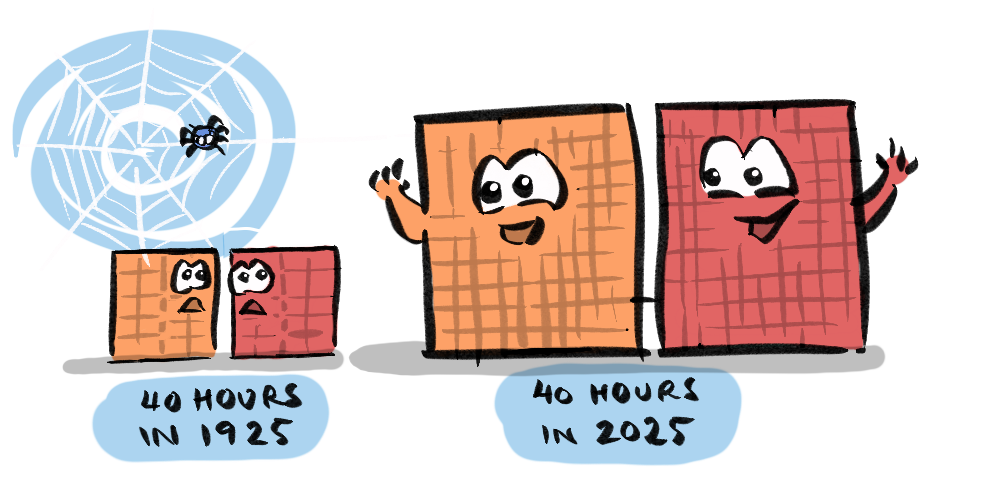

Now, assume that productivity in standard goods quintuples by 2025, so that each labour hour generates 5 standard goods units. For 20 labour hours, you now get 100 units of standard goods.

However, we shouldn’t expect the same productivity gains for housing, as the supply of land is relatively fixed. Let’s assume for now that the productivity of housing stays the same.

You might think that, since we’ve gotten so much more efficient at making standard goods, we can work less. If we want to consume just 60 units of standard goods (three times as much as in 1925), that should cost only 12 hours of work (as 60 / 5 = 12) instead of 20 hours.

Does that mean we can now enjoy more consumption plus an extra 8 hours of leisure each week?

Not so fast. At least, not if you want a house to live in. Because the price of land has now gone up! Since everyone else has figured out they don’t need to work 20 hours per week to buy all the standard goods they could want, they’re now channelling all those extra hours towards bidding up land prices.

End result? You’re back to working more or less 40 hours per week. You get more standard goods for your efforts (60 units instead of just 20), which is nice, but no more leisure.

Admittedly, this is a hypothetical and highly simplified example. But there is some data to suggest the underlying dynamic exists. Between 1900 and 2003, the average American household’s share of spending on food and clothing declined considerably, from over half their budget to less than 20%.3BLS 100 Years of U.S. Consumer Spending: Data for the Nation, New York City, and Boston. At the same time, the share of spending going to housing grew from less than a quarter of their budget to around a third.4The shares have not changed significantly since 2003. See BLS Consumer Expenditures – 2023.

Eagle-eyed readers may notice that the increase in spending on housing for American households has not been nearly as dramatic as in my hypothetical example above. That’s because my hypothetical example illustrates what could happen if we threw nearly all our savings from productivity gains into a single zero-sum game (land). It’s like a “worse case scenario” where productivity gains are almost fully negated (“almost” because we still increase our consumption of standard goods).

Thankfully, things in real life aren’t quite as bleak. As I explain in my second post, there are ways to get out of this zero-sum competition and we have used some of them.

Question: Where does the money and time go?

If we’re getting more efficient at producing standard goods and putting our extra resources into competing for relatively fixed amounts of status and land, where do those resources “go”?

The answer depends on the competition in question. When people compete to become better educated or smarter, those extra resources might go to time spent studying or reading. When people compete to become more physically attractive, those extra resources might go to the fashion and weight loss industries and plastic surgeons. And when people compete for land, existing owners get windfall gains.5This is a strong argument for a land value tax such as that advocated under Georgism. It won’t change the nature of the zero-sum competition, but it can at least redistribute those windfall gains.

Can we do anything about this?

Returning to the title of this post, “Can zero-sum games negate productivity gains?”, I would say the answer is “Yes”. Zero-sum games can negate productivity gains. But they don’t have to.

To be clear, I am not saying that the past was better, or that productivity gains over the last 100 years have all been for naught. There are still many benefits to being able to manufacture goods using fewer resources. Increasing productivity is a great first step. I just don’t think we can stop there. Productivity gains may simply allow us to throw more resources into competing over land and status. We won’t realise the full benefits of productivity gains if we’re still stuck in some zero-sum games.

We therefore need to find ways to extract ourselves from zero-sum games. That is the focus of my second post, which you can find over at Non-Zero-Sum Games.

What do you think of my arguments? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

- 1“Standard of life” as measured by real GDP per person. See Beretta et al (2024) and Crafts (2022).

- 2My second post takes a closer look at how fixed the supply actually is, especially for land.

- 3

- 4The shares have not changed significantly since 2003. See BLS Consumer Expenditures – 2023.

- 5This is a strong argument for a land value tax such as that advocated under Georgism. It won’t change the nature of the zero-sum competition, but it can at least redistribute those windfall gains.

5 thoughts on “Can zero-sum games negate productivity gains?”

This is really interesting and thought-provoking (and the pictures are really cool). But does this rely on the good in fixed supply (land) being a status good itself? I think it must?

The reason I ask is because I’m a little unsure at an economy wide level that competition for land from a status perspective is bad – in fact, I think status competition for a good in fixed supply might be the *best* type of status competition.

Let’s think about two potential markets that people might compete for positional goods in. The first is land. Owning the nicest land makes you higher status so if you care about status you want to own the nice land. Land is in fixed supply.

The second is diamonds. In this hypothetical, the only value of diamonds is from status. The shiniest diamonds are the highest status. Diamonds are *not* in fixed supply.

I think it’s far better if people compete for the status-land than the status-diamonds.

Here’s why: let’s imagine a status-obsessed priest. This priest fulfills the spiritual needs in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. And weirdly, this priest receives an hourly rate.

If the priest is status obsessed with diamonds, working extra hours provides more spiritual needs, but it also gives him more money to buy more and shinier diamonds. Because of this, the proportion of the economy’s actual real resources (machinery, human labour) devoted to digging shiny stuff out of the ground has to increase.

But if the priest is status obsessed with land, then working more hours to provide spiritual needs results in higher land prices, but none of the economy’s actual real resources (machinery, human labour) need to be pulled away from other good Maslow stuff and devoted to land.

So in that case, I think you’d much rather the status good was in fixed supply.

Am I way off base?

Thanks Phil! You raise an interesting point and I agree that in your example it would be better for society if the priest were obsessed with land rather than diamonds. My post however has mostly focused on what is better for the competitors themselves – the priest in your example. It would be better for the priest not to be obsessed with status at all as he would have more free time. But this would not be better for society so long as the priest’s work generates something net-positive (providing spiritual needs).

I deliberately left out the question of whether status competitions are good for society overall because it will depend on how that competition is determined. That’s a much bigger and harder question (and an interesting one, but my post was already getting rather long).

If the competition is determined by who can provide the most benefit to others such as providing spiritual needs, I expect the pursuit of status should benefit society overall (though you still have to subtract the utility the priest would lose from having less free time, relative to a society where status competitions did not exist). I think this will usually be the case in a liberal market economy if it has rules to discourage anti-social behaviour and consistently and effectively enforces those rules.

However, it’s important to remember that not all competitions are determined so fairly. If the rules don’t prohibit anti-social behaviour or are not consistently enforced, people might be able to win status through misleading statements, rent-seeking behaviour, breaking contracts or even physical violence. Perhaps your priest earns money just by promising to meet people’s spiritual needs without actually meeting them. In this case, the status competitions will likely end up net negative for society – regardless of whether they are competing for land or diamonds.

One further thought on your point that if the priest is status-obsessed with a good in fixed supply, “none of the economy’s actual real resources (machinery, human labour) need to be pulled away from other good Maslow stuff” for it. I’m not sure this is true.

Take the original Mona Lisa as a good whose supply is truly fixed. If we determined who gets it through a simple lottery, no real resources (other than setting up the lottery) have to be devoted to it. But if we determine who owns it through the market then, in the absence of coordination, I don’t think there are any clear limits to how much real resources could be devoted to competing over it – perhaps just physical exhaustion for labour and other physical limits for machinery. It’s true that real resources won’t be pulled away directly to try and make more Mona Lisas, but I think there would still be an indirect pull.

Even in your land-obsessed priest example, his labour hours are a real resource devoted to competing over land. It just happens that those labour hours end up “providing spiritual needs” and doing a good Maslow thing – but as I point out in my above comment, that assumption won’t always hold true.

Hi there! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a collection of volunteers and starting a new project in a community in the same niche. Your blog provided us beneficial information to work on. You have done a outstanding job!

Thanks, glad to hear that my blog is helpful 🙂