This post levies specific criticisms at Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell. Although the book is an entertaining read, it’s riddled with analytical flaws. In my full summary, I mentioned that Gladwell is a very good writer but not much of a thinker. He’ll present an interesting idea that is, at best, a theory, with the conviction of a campaigning politician.

In this post, I’ll delve into the key criticisms I had with Gladwell’s analysis by reference to the specific examples he used. You can read my full summary of Talking to Strangers for more context.

Jerry Sandusky

In 2001, one assistant coach saw Jerry Sandusky, another assistant coach, showering with a young boy in a locker room. The first assistant coach reported it to the head coach, who in turn reported it his boss, Tim Curley. Curley then reported it to a senior administrator, Gary Schultz and Schultz reported it to the school’s president, Graham Spanier.

However, when the incident was reported further up the chain it was described as “horseplay” and “horsin’ around”, not as sodomy or sexual assault. Curley and Schultz were both convicted of conspiracy, obstruction of justice and failure to report child abuse. Spanier was fired and eventually convicted of child endangerment.

Gladwell thinks that people treated Spanier (and possibly Curley and Schultz) unfairly. He agrees that they made a mistake in retrospect in defaulting to truth (i.e. believing what people say at face value). But Gladwell argues that is a fundamentally human tendency and is not a crime. He writes:

We think we want our guardians to be alert to every suspicion. We blame them when they default to truth.

I agree that defaulting to truth is generally reasonable. In fact, it’s baked into the law — the standard of proof in criminal cases is beyond reasonable doubt. But that doesn’t mean we should just shrug and say “oh well, default to truth” whenever people drop the ball.

Defaulting to truth can, and probably should, be a crime if possible sexual abuse of a child is involved. It is reasonable for society to expect people to be more suspicious when the stakes are high, particularly where those people are adults entrusted with the care of vulnerable children. While we may not want our guardians to be alert to every suspicion but we may want them to be more alert to suspicions involving sexual abuse.

Larry Nassar

Gladwell used the Larry Nassar case as an example of defaulting to truth (the tendency to assume people are being truthful). He claims this was why most parents didn’t believe Larry Nassar was doing anything wrong, even when their daughters told them otherwise.

But not believing your daughter is being molested isn’t defaulting to truth. If it was, why wouldn’t parents default to believing their daughters? Their thought process was more likely to be a mixture of:

- not wanting to believe something terribly disturbing had happened to your daughter, especially while you were present, and

- taking into account base rates. Objectively, it’s more likely that there was a misunderstanding than that your daughter’s physician repeatedly molested her. The vast majority of physicians aren’t child molesters, but honest mistakes happen all the time — and young children often misunderstand things.

That’s not to say defaulting to truth isn’t a thing — I’m sure that humans do default to truth. Annie Duke explains this tendency much more compellingly. Gladwell, on the other hand, seems to conflate defaulting to truth with applying base rates (which is a different thing) and presumption of innocence. It’s quite surprising that Gladwell didn’t mention the legal presumption of innocence at all when discussing “default to truth” in cases of criminal misconduct. It’s a rather glaring omission.

Brock Turner

This case was extremely high profile and involved a sexual assault at Stanford. Brock Turner, a promising young swimmer, was found thrusting on top of an unconscious and partially-naked woman outside a frat party. Despite being found guilty of sexual assault, he received a sentence of only 6 months in jail, with 3 years of probation, sparking widespread public outrage. He ended up serving just 3 months.

Let’s do the good stuff first. On one hand, I appreciate that Gladwell is not afraid to voice an unpopular opinion on controversial issues. And I think he is right to point out that college drinking culture is unhealthy, can make it difficult to determine consent, and contributes to many sexual assaults. Not only does alcohol make it difficult for people to determine consent in the moment, it also makes it harder to work out what happened later (e.g. in court) because of its effect on people’s memories.

Sexual assault cases are hard

Now onto the bad stuff. Sexual assault cases involving disputes over consent are hard. Given Gladwell’s general lack of rigour, proclivity for stating opinions as fact, and tendency to shoehorn things to fit his theories, I wish he had steered clear of this one.

The main reason sexual assault cases are hard is not because, as Gladwell suggests, it is so difficult for the people involved to work out if the other person is consenting. Again, people can always, you know, ask. No, the reason these cases are hard is because there are usually no witnesses involved, so it comes down to the credibility of people giving two differing accounts. The man typically gives evidence about how well things were going and how all signs suggested she was consenting. The woman will usually say that she didn’t consent, felt uncomfortable or maybe scared, and tried to make that known.

It’s hard for a case to reach the criminal standard of “beyond reasonable doubt” when it’s just one person’s word against another. And the whole judicial process, particularly cross-examination, is pretty traumatic for victims of sexual assault. It’s safe to say that most sexual assaults will not result in a conviction. Many assault victims don’t even bother pressing charges because they just want to put the matter behind them, don’t want to go through the cross-examination process, and understand that the odds are stacked against them. That’s why these cases are hard.

But the Turner case was uncharacteristically easy for a sexual assault case

The Brock Turner case was one of the worst possible cases he could’ve used to illustrate this point. Gladwell deliberately picked a well-known and infamous case. He knew it would get people’s interest and draw attention to his book. Unfortunately, by using the Turner case to illustrate his point, Gladwell suggests that Turner made a reasonable attempt to work out if Chanel Miller was consenting but he made a mistake. Based on the facts in that case, that’s just wrong. Miller was unconscious. Independent witnesses testified that they saw her unconscious. And, legally, an unconscious person cannot consent to sex.

This was not a case of mistaken belief in consent. It was a case about a guy taking advantage of an unconscious woman, not caring if she consented.

I should also point out that in California, as in many other jurisdictions, an actual and reasonable belief in consent is a valid legal defence. Even if that belief was mistaken. Gladwell’s failure to point this out is a glaring omission. He leaves you with the impression that Turner was held to unreasonably high standards:

Brock Turner was asked to do something of crucial importance that night – to make sense of a stranger’s desires and motivations. That is a hard task for all of us under the best circumstances, because the assumption of transparency we rely on in those encounters is so flawed. Asking a drunk and immature nineteen-year-old to do that, in the hypersexualized chaos of a frat party, is an invitation to disaster.

Society wasn’t asking Turner to “make sense of [Miller’s] desires and motivations. It merely asks that he not have sex with an unconscious person. It’s really not that difficult. Here’s a quote from Miller’s victim impact statement:

Brock stated, “At no time did I see that she was not responding. If at any time I thought she was not responding, I would have stopped immediately.” Here’s the thing; if your plan was to stop only when I became unresponsive, then you still do not understand. You didn’t even stop when I was unconscious anyway! Someone else stopped you. Two guys on bikes noticed I wasn’t moving in the dark and had to tackle you. How did you not notice while on top of me?

The Turner case was not a hard case. It was actually an unusually easy case.

The Turner case was absolutely the wrong case to use

Gladwell’s overall point was that it can be really hard to read strangers (i.e. work out if they’re consenting or not), and that alcohol makes that task harder. In itself, that is not an unreasonable point. But that point would have been stronger in another case — possibly the Benjamin Bree case, which Gladwell mentioned in the same book, and which resulted in an acquittal. (Although again, I want to point out that people can always ask! These are not cases like Hitler or Madoff where the person is actively lying to you.)

Coupling

Coupling is the idea that behaviours are linked to very specific circumstances and conditions. Gladwell argues that crime is coupled with particular locations while suicide is coupled with suicide methods. I don’t disagree with Gladwell’s general point that context is important. But his analysis is pretty dodgy.

Crime hotspots

According to Gladwell, crime is linked to specific places and contexts, and increasing police presence in those areas can reduce crime in a city, rather than simply displacing it. However, there are some issues with this analysis. For one, Gladwell doesn’t distinguish between different types of crime, some of which may be more location-specific than others. For instance, domestic violence may occur repeatedly in a single home, but evicting the offender may not necessarily stop the violence.

Another criticism of Gladwell’s argument is that he doesn’t address the long-term effects of increasing police presence on crime. He cites a study by Weisburd which found that increasing police presence in a prostitution hotspot reduced prostitution by two-thirds. While this may seem like a significant achievement, it’s unclear what happened to the women who left prostitution. Did they successfully transition to other occupations? And what about the demand for prostitution? Did other women simply fill the void left by those who left? These questions are not addressed at all (not even to mention whether Weisburd discussed them).

In summary, while Gladwell’s argument has some validity, it oversimplifies the complexity of crime and overlooks the potential long-term consequences of police interventions.

Suicide

Gladwell claims that suicide is coupled with suicide methods, such that we can reduce suicide rates by removing some suicide methods. Now, I agree with Gladwell that not everyone who attempts suicide once will necessarily find a way to kill themselves. And making it harder for people to kill themselves generally sounds like a good thing.

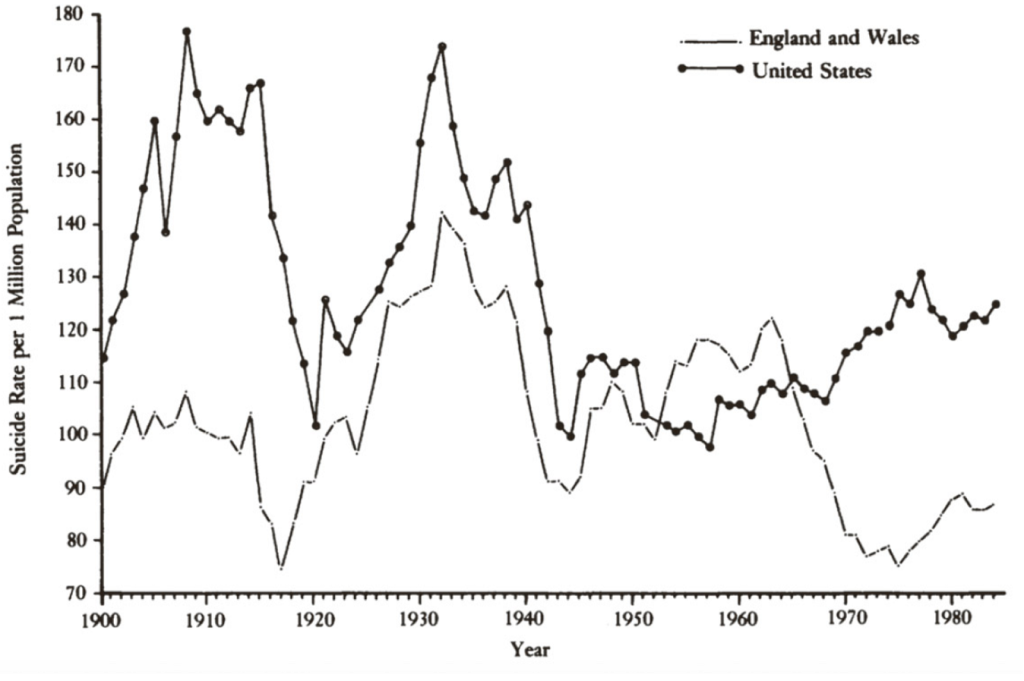

However, to support his claim, Gladwell refers to this chart showing suicide rates between 1900 to 1990:

He argues that suicide rates in England and Wales “plung[ed] down” when town gas (a popular suicide method) was phased out of home ovens from the late 1960s. (I note that, instead of adding a caveat that correlations do not imply causation, Gladwell frequently encourages you to infer causation!)

There are two problems with this:

- The Y-axis for the graph starts from 70, not 0, making the fluctuations look larger than they actually are. The rate Gladwell claims is “plunging down” seems to be a decline from around 120 suicides per million to around 80 per million. A significant drop of 33%, sure, but not as big as it looks in the graph.

- More importantly, the UK only started phasing out town gas from 1967. Suicide rates had already fallen to around 90 per million by this time. Most of the decline from the early 1960s peak seems to have occurred before 1967. So what’s the reason for that?

Finally, Gladwell used the examples of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton (who both commited suicide) to illustrate his point. By Gladwell’s own description, both were fascinated with the idea of suicide and seemed determined to kill themselves. Both made multiple suicide attempts. As with the Brock Turner case, Gladwell seems to have picked the example because it was famous, not because it was a good example.

Sandra Bland

In 2015, a police officer, Brian Encinia, pulled over Sandra Bland, a young, black woman, for failing to signal when changing lanes. The altercation gets heated and the officer ends up arresting Bland when she refuses to get out of her car. Three days later, she kills herself in custody. Many people saw this as a case of a rogue or racist cop bullying a black woman just because he could.

Gladwell disagrees. He greatly plays down Encinia’s responsibility in this case and blames his training instead. I’m not sure if he was right to do so. For example, he seems to accept at face value Encinia’s claims that he was scared Bland might have a weapon. But this was a self-serving claim, so deserved more scrutiny than Gladwell gave it.

Surprisingly, Gladwell does not focus much on race when discussing this case. He mentions in passing the fact that police stop black people more often. A lot of the analysis about demeanour clues and race is, for some reason, in a very long footnote rather than in the main text.

Another glaring omission is Gladwell’s failure to explain what the law in Texas was. Could Encinia legally order Bland to step out of her car? He certainly seemed to think so, while Bland certainly did not. If Encinia did have that right, perhaps Bland’s death could have been avoided had she known. She may have complied quickly and not been arrested at all. And if Encinia knew he did not have that right, perhaps he wouldn’t have been so aggressive toward Bland. So maybe it was a mistaken understanding of police powers (either by Encinia or Bland) that sadly caused Bland’s death.

Conclusion

Overall, the analysis in Talking to Strangers is superficial and flawed. Gladwell cherry-picks his examples, omits relevant facts, and fails to anticipate and respond to counterarguments. Worse, he doesn’t even cherry-pick the right examples to support his claims — just the most famous, attention-grabbing ones. As with most of Gladwell’s books, Talking to Strangers can be an entertaining read, but one you should approach with a healthy dose of scepticism.

If, despite my above criticisms, you still you want to get Talking to Strangers, you can do so at: Amazon | Kobo <– These are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you buy through these links. I’d be grateful if you considered supporting the site in this way! 🙂

Do you agree with my criticisms or think I’m being too harsh on Gladwell? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

If you enjoyed this post, you may also wish to check out:

- My full summary of Talking to Strangers

- Book Summary: Calling Bullshit by Bergstrom and West, to help you identify other cases of shaky analysis and misleading claims

- Criticisms of Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber

7 thoughts on “Criticisms of “Talking to Strangers” by Malcolm Gladwell”

Honestly you weren’t harsh enough. The book was terrible. I am never the person to put a book down but at about a quarter of the way through I already thought this is such a waste of time. I’m not quite finished with it yet and I think I might just leave it.

This is my first Malcolm gladwell book and I assumed because he’s popular. He’s not a total idiot… I think I’m wrong about that.

He also seems to make the claim that people tell the truth most of the time and that people believe them most of the time. I feel like he lied in the book and I feel like I didn’t default to truth when I read it because I feel like he’s a liar based off of what I read. Or he simply dumb. Or maybe I’m just not imaginative to discover that there is a third reason that he would publish a book of untruths.

Thanks for commenting. Yeah, if you’re already hating it you should just leave it – it only gets worse from there.

I’m not sure if Gladwell deliberately lies. I think he’s just reckless with the truth – he basically doesn’t care if something is true or not, as long as it’s entertaining. It’s rather concerning that he used to be a journalist. Maybe he’s just used to other people checking his facts for him.

I agree with your general sentiment that Malcolm Galdwell’s presentation of information has meaningful flaws, including that he presents theories as facts and implies causation when there is only correlation. However, many of your more specific criticisms seem like they are missing the points that he is making. For example, my read of the Brock Turner segment of the book was not that he believes that Turner is innocent or should not be punished. Instead, I understood him to be attempting to explain his behavior that night and otherwise why sexual assaults are so common on college campuses. I believe that he presents a theory that is interesting to think about (in that it has potential implications for how society could consider targeting the issue), so the main point where I diverge with him is in his certainty that addressing this issue would effectively address the problem.

I appreciate the criticism overall as part of what makes reading books like this interesting is engaging in the critical dialogue that it sparks. However, I think that several of your points fall into a similar pattern to my example above of distorting the claims that I understood Gladwell to be making.

Hey, thanks for your thoughtful comment and constructive feedback.

On the Brock Turner case, I didn’t mean to imply I thought Gladwell believes Turner is innocent or that he shouldn’t be punished. I understand Gladwell’s main point was that it’s hard to understand what other people are thinking and so it’s hard for young people to understand if someone is truly consenting to sexual activity, especially at a frat party where both people are drunk. That is a completely valid point. I just think the Brock Turner case was absolutely the wrong case to illustrate that point because the question of consent was far more straightforward than it is in your typical case involving sexual assault. As I said in my post, it sounds like the Benjamin Bree case would have been a much better example to use. I still stand by that.

It’s been a while since I read the book so I accept it’s very possible I might be missing Gladwell’s points on some other areas. I appreciate you pointing this out to me though and it’s a good reminder to take care in making sure I understand an author’s key points.

I can see your point about the selection of the Turner case vs the Bree case. You may be right that the Bree case could have been a more interesting focus. Your point also causes me to debate with myself about whether the extreme nature of Turner’s behavior does make give make it interest for a different reason however. By this I mean that it is very hard for me to put myself in Turner’s perspective here, which makes me wonder what drove him to act this way. I don’t think Gladwell has fully explained his actions with his theory but it did make me think about whether the effects of alcohol impact my social perceptions more than I had previously realized. So I appreciated the choice of example from that perspective.

Similarly, in the Sandusky case, I’m not sure I am willing to excuse the members of the Penn State staff to the degree that Gladwell has based on his default to truth theory. However, I still appreciated that his account gave me something to think about. I assume that both you and I would heavily condemn failing to report child sexual abuse. However, his argument made me wonder how easily I might fall into the trap of looking for alternative explanations for such a report if put in that situation as well given the types of biases humans seem to have. I think I agree with you that filing it all under “default to truth” is forcing the point a bit, but I appreciated the example despite this flaw.

I am most compelled by your critique of his suicide chapter. I does seem that he is guilty of both equating correlation and causation and of reading the graph in a biased manner. Readers of his audio book (my method) don’t have access to the chart (not sure if it actually makes an appearance in the physical copy), which robs them of the ability to do their own analysis of it. To me, this is a much more misleading practice that I find harder to forgive.

Yeah, I think the Sandusky example is thought-provoking. There I was more disagreeing with the extent to which he thought default to truth could excuse the staff’s actions. But, like you, I don’t know how I would react in that situation and I don’t fault Gladwell for using it as an example.

I also wonder if the tone of the audiobook version (which I understand Gladwell narrates) may give a different impression than the one I got from reading the book. There is obviously quite a lot lost in written text and perhaps Gladwell’s narration is more questioning/ambivalent in tone than I interpreted his text.

You’re right that he does narrate it. That’s a good point – it’s definitely possible the tone is different when I heard him telling it. It also just might humanize him more, which would make me more inclined to have a generous interpretation.