Estimated reading time: 15 mins (or see my conclusion for the 1-min summary)

This is the first of three posts criticising The Case Against Education by Bryan Caplan. (Click here for a detailed summary of the book). It is the most extensive criticism I have done to date. All up, I’ve probably spent ~40 hours reading, summarising, and writing up my criticisms of this book.

I have occasionally wondered whether I was wasting my time giving air to someone who so clearly enjoys being provocative. However, there were three reasons why I thought this book was worth criticising in detail.

- First, on my initial reading of the book, I largely bought Caplan’s arguments. He made many good points and generally came off credible (albeit radical). He acknowledged where his data was weak and seemed to make a real effort to tease out different factors and address counterarguments. But when I wrote up my summary, I spot-checked some of his sources and calculations. The more I dug in, the less I trusted him.

- Second, many criticisms of The Case Against Education seem quite shallow. Many go for the low-hanging fruit, like Caplan’s polemical tone and his most extreme recommendations. Others bring up points that Caplan’s already dismissed, such as “signalling can’t be true because IQ tests would be so much more efficient” or “what about the intangible benefits?” I haven’t seen any challenge his underlying calculations or references.

- Lastly, some of Caplan’s claims could do real harm. Caplan isn’t just some rando—he’s an economics professor at George Mason University with multiple books to his name. He also seems skilled at getting publicity for his work as I’ve heard him on multiple podcasts, including a few that I respect.

My aim is to present a more thorough and balanced criticism of Caplan’s claims than I’ve seen to date.

This first post starts by acknowledging the points I think Caplan gets right. I then point out how Caplan really only presents a case against higher education. For high school, the social returns on Caplan’s own calculations are actually quite solid. For early childhood and primary education, Caplan’s case is virtually non-existent as he misrepresents research and even relies on a fabricated study to support his claims.

My second post describes how Caplan seriously overstates the case for signalling in general by conflating signalling and ability bias. I’ll also explain how that affects the implications for what we should do.

My final post looks at Caplan’s math, in response to his complaint that “No One Cared About My Spreadsheets”. I cared, Bryan. But your spreadsheets were pretty crap.

Disclaimers

I am not an expert in education policy, child development or labour economics. My criticisms are based on The Case Against Education itself, the studies referred to in it, and Caplan’s spreadsheets.

I don’t have any personal experience with the US education system. I went to university in New Zealand and studied business and law.

See also Why I write criticisms of books.

What I think Caplan gets right

Before I launch into my criticisms, I want to take a moment to acknowledge the many things I believe Caplan gets right:1As noted above, I am not familiar with the US job market or educational system so I don’t know if Caplan is actually right on all these points. But they match up with my personal non-US experience and I didn’t detect any obvious errors or inconsistencies in these arguments.

- Much of the education earnings premium is not driven by increased human capital (at least for higher education).

- To work out if education is a good investment, you have to account for failure rates.

- Signalling is a zero-sum game with little if any social benefit.

- We should judge public education spending according to its social return.

- What you study affects future earnings more than where you study.

- There is a lot of useless stuff in the academic curriculum. Though Caplan overplays this, I liked his point about how people learn best when they have an opportunity to apply what they’ve learned shortly after learning it. But since most of what is taught in school isn’t practical, there are few such opportunities and retention is poor.

- Traditional academic education is not that good at teaching broad, transferable skills like critical thinking. I think I personally learned some of this in school but I suspect I learned far more outside it—at work, through reading, and from peers.

- Vocational education is underrated.

- Alternatives to education like work or even play can be enriching.

All this to say—I am far from a human capital purist. I enjoyed school for the most part, but also found it a terribly inefficient way to learn. I much prefer self-directed learning and am very enthusiastic about Khan Academy and online courses. So the premise of The Case Against Education was music to my ears. But that was partly why it was such a disappointment. Caplan’s sloppy work and unnecessarily combative tone undermined his general credibility and tainted his stronger arguments.

The Case Against Higher Education

The Case Against Education is mostly the The Case Against Higher Education. More specifically, it’s The Case Against Government Funding of Higher Education, since Caplan acknowledges that college has great selfish returns for most students.

Caplan’s case against “education” in general has at least three problems:

- First, the social returns from high school are pretty decent under anything but the most extreme signalling assumptions.

- Second, most public education funding is for K-12, not higher education.

- Lastly, the case against primary or early childhood education is virtually non-existent. It relies on a fabricated study, some cherry-picked findings, and outdated heritability research.

First problem: Social returns from high school are decent

Although Caplan doesn’t advocate eliminating public funding for high school, he wants to impose some tuition costs. His argument is that this would reduce attendance and make high school graduates scarcer, thereby increasing the value of a high school diploma. Both the earnings premium and social returns from high school should then increase. At some point, it may reach a “respectable” level of, say, 4%.

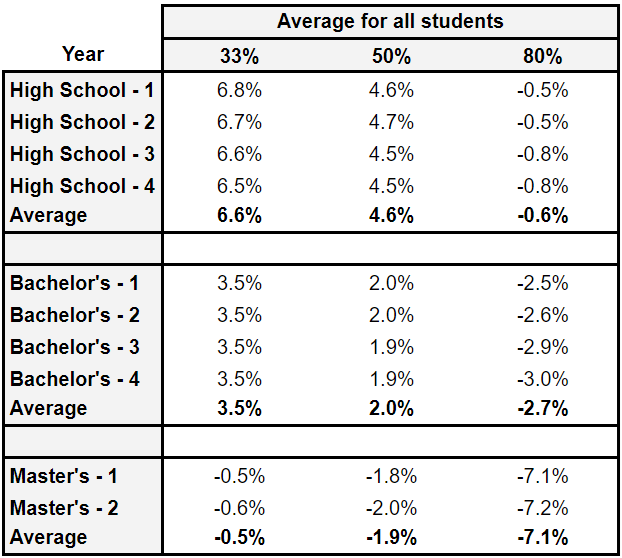

My table below summarises Caplan’s own figures (from his Chapter 6 files). As you can see, high school comfortably meets a 4% return even assuming a hefty 50% signalling share.

Now, if you think signalling makes up considerably more than 50% of the high school earnings premium, you could still argue the social returns fall short of a 4% return. However, my larger table which breaks down social returns by the types of students shows that the highest social returns from high school are from Poor Students, who yield an average 6.8% return with 50% signalling. This is because education reduces their propensity towards crime, and crime has enormous social costs.

“Poor” primarily refers to academic performance rather than family income, but I expect Poor Students are also more likely to be financially “poor”, too. Moreover, since Poor Students earn the lowest selfish return to high school, they’re already more likely to drop out than other students. So Caplan’s recommendation to impose tuition costs for high school is most likely to turn away the students whose social returns are the highest.

Second problem: Most education funding is for K-12

Okay, so Caplan’s case against higher education is much stronger than his one for K-12. Shouldn’t we still reduce funding for higher education?

If that had been the extent of Caplan’s arguments, I wouldn’t be writing this post. I think some degree of higher ed funding could still be justified on the basis of positive externalities from academic research.2I assume externalities are net positive, even after we subtract out any negative externalities from books like Caplan’s. But I suspect we could fund that far more efficiently—e.g. funding the research directly, rather than indirectly via tuition subsidies and cheap student loans.

The problem is that Caplan complains about excess government spending on “education”, even though most (around 64%)3Caplan notes the US government spent $565 billion on K-12 education and $317 billion on higher education (based on 2010-11 figures). is spent on K-12 and generating respectable social returns. He compares this to national defence spending:

Government support for education comfortably exceeds notoriously bloated defense spending. Even at the height of the War on Terror, there was more government money for education than the military. Government spending on education is about 6% of the whole economy.

This comparison is nonsensical. The US has over 50 times more students (almost 80 million in 2021) than it has active duty service members (fewer than 1.5 million in 2020).4US Census – US Armed Forces at Home and Abroad. Of course, defence spending also includes equipment, and military equipment is expensive. But that just shows how silly it is to compare two headline figures and say, “Oh, this one’s bigger.” It’s like saying: “Many people think we incarcerate too many people and that we don’t invest enough in our public services. However, the US has fewer than 2 million prisoners, which is around half the number of federal employees.”

I have no opinion on whether the US spends too much or too little on defence or education. I’m just saying Caplan’s comparison is ludicrous.

Third problem: The case against primary and early childhood education is non-existent

While The Case Against Education mostly deals with high school and college, Caplan can’t resist taking jabs at primary and early childhood education. He writes:

All things considered, I favor full separation of school and state. Government should stop using tax dollars to fund education of any kind. Schools—primary, secondary, and tertiary alike—should be funded solely by fees and private charity.

To be fair to Caplan, this quote comes from a section titled “What I Really Think”. He points out it’s near-impossible to estimate primary education’s selfish or social returns because almost everyone in the US goes through it. So he acknowledges that the case against government funding of primary education is “definitely weaker”. That’s an understatement—I’d say his case against primary and early childhood education is virtually non-existent.

Early childhood programs

Caplan refers to several early childhood programs that apparently failed to maintain their gains in boosting IQ:

Making IQ higher is easy. Keeping IQ higher is hard. Researchers call this “fadeout”. Fadeout for early childhood education is especially well documented. After six years in the famous Milwaukee Project, experimental subjects’ IQs were 32 points higher than controls’. By age fourteen, this advantage had declined to 10 points. In the Perry Preschool Program, experimental subjects gained 13 points of IQ, but all this vanished by age 8. Head Start raises preschoolers’ IQs by a few points, but gains disappear by the end of kindergarten.

Neither the Milwaukee Project nor Perry Preschool Program support Caplan’s position. A quick Google reveals that the results in the Milwaukee Project were completely fabricated. Rick Heber, the project’s director, was convicted of fraud and misuse of federal funds and sentenced to 3 years in prison.5See also: Gilhousen et al (1990) and Page (1986) if you don’t trust Wikipedia. So it’s not a study anyone should be citing.

The Perry Preschool Program was a proper study, but the results are far more positive than Caplan portrays. While it’s true that IQ gains disappeared by age 8, the 2011 meta-analysis Caplan cites finds positive effects on other achievement tests through to age 27. Additionally, the kids who went through the program enjoyed better outcomes in various other areas: less youth misconduct and crime, higher high school graduation rates, higher earnings as an adult, less dependency on social welfare and better health. If true, these seem like excellent results for a program that took only 2.5 hours per day over a school year!

The meta-analysis concludes:

Early educational intervention can have substantive short- and long-term effects on cognition, social-emotional development, school progress, antisocial behavior, and even crime. A broad range of approaches, including large public programs, have demonstrated effectiveness. Long-term effects may be smaller than initial effects, but they are not insubstantial. These findings are quite robust with respect to social and economic contexts.

To repeat my earlier disclaimer: I am not an expert on child development psychology. But, clearly, neither is Caplan. I have no idea how reliable the 2011 meta-analysis is. Yet doing the bare minimum in due diligence (i.e. skimming the paper) reveals a very different picture from the one Caplan paints.

Nature vs nurture

Caplan’s scepticism of childhood education seems to be rooted in his deeper underlying beliefs about heritability. In the perennial “nature vs nurture” debate, Caplan comes down firmly on the “nature” side. He asserts that twin studies consistently find “strong, pervasive effects of nature, and weak, sporadic effects of nurture”. He continues:

In developed countries, nature doesn’t merely dwarf nurture on physical traits like height, weight, and longevity; nature also dwarfs nurture on psychosocial traits like intelligence, happiness, personality, education, and income. The genes your parents give you at conception have a much larger effect on your success than all the advantages your parents give you after conception.

I agree that people often overlook the role of nature. But heritability is a complex topic, which Caplan oversimplifies and distorts. His assertion that behavioural geneticists “have isolated the effects of upbringing” on things like educational attainment and income is far too strong. The evidence simply doesn’t support it.

This Clearer Thinking post gives a great and accessible explanation of heritability. It’s well worth reading in full but, for now, the two key points are:

- Contrary to popular belief, heritability does not mean a trait is fixed or unchangeable. For example, height is usually considered highly heritable, yet it’s also impacted by environmental factors such as nutrition.

- Heritability describes how much of the variation in a group can be explained by genetic differences. As such, heritability can change depending on how uniform environmental factors are across a group. So height would likely be more heritable in an environment with uniformly abundant nutrition than in one where nutrition was scarce and variable.

This means heritability studies can’t tell us anything about the effectiveness of an environmental factor like primary education6To be clear, Caplan doesn’t bring up twin studies to argue that primary education doesn’t matter, but that education and upbringing in general don’t matter that much. However, since he doesn’t provide any evidence to support his case against primary education, I’m assuming it’s based on a similar line of reasoning. if pretty much everyone gets the same “treatment”. Even if primary education was extremely good at improving happiness, productivity and income, we’d still see high heritability for those traits. This would not mean nurture “doesn’t matter”. It’s just that standardising an environmental factor (primary education) allows genetic factors to play a larger role in any variation.

Lastly, newer, DNA-based methods that try to directly measure heritability find much lower estimates—often less than half—compared to the twin studies. Scientists have been debating this “missing heritability problem” since around 2008. Caplan’s book was published in 2018, so he could’ve known this. I suspect he just never bothered to update his research as every relevant reference I found was to his 2011 book (Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids) or earlier.

Conclusion

To summarise my first tranche of criticisms of The Case Against Education:

- Public education spending is mostly on K-12.

- On Caplan’s own figures, K-12 education already shows good social returns (4% with a 50% signalling assumption).

- Tuition costs for high school are most likely to deter Poor Students, who yield the highest social returns (6.8% with 50% signalling).

- Comparing education and national defence spending is stupid and meaningless

- Caplan’s case against early childhood and primary education is non-existent. It’s based on a fabricated study and cherry-picked findings, and supplemented by outdated heritability research.

Overall, The Case Against Education would have been a much better book had Caplan solely focused on higher education. Its arguments against early childhood, primary, and secondary education were so weak and full of holes that I actually revised up my estimation of all three. It was a good reminder for me how important checking references can be.

I hope you enjoyed this post. Please let me know in the comments or using my contact form if you think I got anything wrong.

If, for some reason, you still want to buy The Case Against Education, you can do so at: Amazon <– This is an affiliate link, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through it. Thanks for supporting the site! 🙂

See also:

- Book Summary: The Case Against Education by Bryan Caplan

- Criticisms of The Case Against Education (Pt 2 — Inflated Signalling Estimates), which explains how Caplan overstates the case for signalling by conflating it with ability bias.

- Criticisms of The Case Against Education (Pt 3 — Checking the Math), which scrutinises Caplan’s spreadsheets and assumptions.

- 1As noted above, I am not familiar with the US job market or educational system so I don’t know if Caplan is actually right on all these points. But they match up with my personal non-US experience and I didn’t detect any obvious errors or inconsistencies in these arguments.

- 2I assume externalities are net positive, even after we subtract out any negative externalities from books like Caplan’s.

- 3Caplan notes the US government spent $565 billion on K-12 education and $317 billion on higher education (based on 2010-11 figures).

- 4

- 5See also: Gilhousen et al (1990) and Page (1986) if you don’t trust Wikipedia.

- 6To be clear, Caplan doesn’t bring up twin studies to argue that primary education doesn’t matter, but that education and upbringing in general don’t matter that much. However, since he doesn’t provide any evidence to support his case against primary education, I’m assuming it’s based on a similar line of reasoning.

2 thoughts on “Criticisms of “The Case Against Education” by Bryan Caplan (Pt 1 — it’s The Case Against Higher Education)”

Thanks this was really interesting.

I agree the comparison between education and defence is weird.

I’m particularly interested in the heritability thing. I read Caplan’s *Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids* and he spends a huge chunk of it going through the twin studies, and I’d never (in that book, if I remember correctly, or elsewhere) come across the point you’d made and similar points in the Clearer Thinking post.

Have you/will you send this post and the others to Caplan? I’ve read his blog for years and he seems to engage with his critics.

Yeah, heritability is interesting and tricky. To be clear I’m not saying that Caplan’s wrong to suggest that nature is very important. It’s just far more complex than he portrays.

I tweeted him the post but didn’t email it to him. Good to hear he usually engages with critics – I might give it a go then (esp to ask about his spreadsheets) but it’s been quite a while since he wrote TCAE so he may well have moved on.