Estimated reading time: 11 mins

This is the second of three posts criticising Bryan Caplan’s book, The Case Against Education (Click here for a detailed summary of the book). My first post argued that Caplan really only presents a case against higher education—his case against high school is rather weak, and his case against primary and early childhood education virtually non-existent.

In this post, I explain how Caplan inflates his signalling estimates by conflating signalling with ability bias. Since his whole thesis is that “signalling” makes up a large—perhaps even the majority of—the return to education, this is quite concerning, and has important implications for what we should do.

Conflating Ability Bias and Signalling

Early in The Case Against Education, Caplan explains the three different arguments for the earnings premium from education:

- Human capital argues the education adds value by equipping people with skills or traits that employers want.

- Ability bias argues that people who choose to pursue more education happen to be the type of people employers wants. Under ability bias, education provides no value at all.

- Signalling argues that education adds value by certifying that people have skills or traits that employers want.

Caplan immediately acknowledges (in my view, correctly) that the reason for the earnings premium is almost surely a mixture of the three explanations. But he later conflates ability bias and signalling, which inflates his estimates for signalling’s share of the premium.

Why does this matter?

Does it matter that Caplan doesn’t give separate percentages for ability bias and signalling? Aren’t Caplan’s calls to reduce public funding still justified? After all, any portion of the premium attributable to ability bias or signalling is not attributable to human capital, so both explanations result in a lower social return.

These are valid points. In fact, I think the case for reducing public funding is stronger when ability bias is high. Those who benefit the most from tuition subsidies will be those with the strongest abilities—i.e. those with the best chances of turning out fine anyway. Moreover, under the signalling model, education still provides some social value by certifying the existence of desirable traits or skills. Under the ability bias model, even that small bit of social value is gone.

So perhaps the breakdown between ability bias and signalling doesn’t matter so much for public funding as both factors point in the same direction. But the breakdown really matters for one question: how do we get out of the zero-sum signalling competition?

How to get out of the signalling trap

Recall that, under Caplan’s model, education signals at least 3 desirable traits: intelligence, conscientiousness and conformity. The latter two are essential to Caplan’s argument because, as he admits, you could easily signal cognitive ability with a standardised IQ test or SAT score. You can’t do that for conscientiousness or conformity.

If Caplan is correct, these two traits entrench education’s position. There’s a catch-22—it would be impossible to signal conformity with anything other than the existing system (at least without some coordinated effort). And even if we found another signal, it still has to be costly and gruelling to signal conscientiousness.

If Caplan is correct, the signalling share of education’s return is as high as 80%. In such a world, anyone who can go to college should, even if they’d rather work or spend their money some other way.

If Caplan is correct, cutting government spending would not solve the problem. Signalling is a zero-sum competition for relative status. While I agree that governments shouldn’t fund zero-sum competitions, eliminating government subsidies won’t eliminate the underlying competition. Education would still send a valuable signal. Any government savings returned via tax cuts could just be spent on more education. Dollars may move from the “public” column of the ledger to “private”, but there’s not much reason to think that overall spending on status would fall. The underlying nature of the game remains zero-sum.1(Added to clarify in response to a comment below: Overall spending on education would presumably fall but, since education is not 100% status, there’s no particular reason to think overall spending on status would drop. And I don’t think we’d be any better off to the extent the education spending is simply replaced by spending on other forms of status.)

Basically, if Caplan is completely correct, there seems to be no way out of this zero-sum signalling trap.

Luckily, I think Caplan is wrong in several key respects:

- Signalling is much lower than 80%;

- College is not a great signal for conscientiousness; and

- Employers don’t value conformity—most people simply are conformists.

Signalling is much lower than 80%

Throughout his book, Caplan repeatedly estimates the signalling’s share of the earnings premium to be between 33% and 80%. Looking more closely, those estimates seem to be for signalling and ability bias combined.

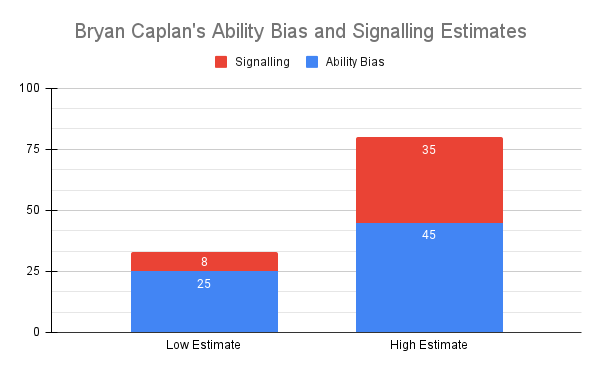

Caplan estimates that ability bias accounts for between 25-45% of the earnings premium (20-30% cognitive ability, and 5-15% non-cognitive). Even the low end of that range is inconsistent with an 80% share for signalling, especially as Caplan concedes some role for human capital.

Now, I’m sure signalling does play a role. Caplan points to the sheepskin effect—where returns to schooling are much higher in graduation years than in any other year (even after correcting for cognitive ability)—which seems to be pretty good evidence of signalling. Unfortunately, Caplan doesn’t provide a clean percentage estimate for signalling as distinct from ability bias.

Working backwards, my best guess of his signalling estimate is between 8% and 35%.2Based on subtracting the 25% and 45% ability bias estimates from the 33% and 80% estimates (respectively). This sounds much less impressive than 33% to 80%, which is why I think Caplan deliberately obscured it by conflating ability bias and signalling.

College is not a great signal for conscientiousness

While I agree that a college degree signals some conscientiousness, I don’t think it’s a great signal. Caplan seems to agree. He argues that college today is too easy. Full-time college students spend only 27 hours per week study, down from 40 hours in 1960.

So there are many plausibly superior signals of conscientiousness—say, full-time work, joining the army or starting a business. Other possibilities might include building a mobile app, maintaining a website, or running a triathlon.

But wait—Caplan claims these alternative signals won’t work. His argument is that employers value conformity, and it’s simply impossible to signal conformity in non-conformist ways. It’s a very convenient argument. But is it true?

Most people are conformists, not signalling it

I’m sure some employers value some degree of conformity. I expect this is more likely true for large employers who have well-defined, standardised roles. If they just need to replace one cog in the machine with another, it’s easiest if they can find someone who has been doing exactly the same job in another company. But I doubt this desire for conformist employees is universal.

The only “evidence” Caplan provides for employers valuing conformity is that they don’t seem to take online credentials seriously. Yet that’s likely because many online credentials are free and very easy to get, with mostly multiple-choice tests and almost no anti-cheating measures. Paid credentials should be better signals and, for what it’s worth, I have heard anecdotal reports of people getting jobs at prestigious organisations with credentials like the MITx MicroMasters or Google Career Certificate.3Admittedly, I only know of people who already had a college degree and work experience using online credentials to change career paths. But that’s probably because I live in a bubble and know very few non-college grads, period. However, hiring managers still struggle to understand online credentials. While “normal” colleges are ranked by organisations like US News, QS World or the Times Higher Education, there’s no credible system that rates online credentials (yet, anyway), making them inferior signals.

But surely college is a sign of conformity! So many people go without giving it any real thought!

And, yes, I think that’s true. While I accept that college signals some degree of conformity, I think it’s a largely irrelevant and weak signal. I can think of many people who have completed a college degree but are far too non-conformist for the typical corporate job. The way you dress and act in a job interview reveals far more about whether you’ll fit into a particular workplace than whether you have a college degree.

Why do so many people go to college?

If college is such an expensive and inefficient way to learn things, why do so many people go?

I think students fall into two broad camps.

The first camp uses college as a commitment device. Like signing up for an annual gym membership, the sunk cost is the attraction. One reason why completion rates for online education are so low is because it’s too cheap and easy to sign up for courses. When students face a challenge, it’s tempting to just give up and tell themselves they’ll try again later.

The second camp goes out of peer and parental pressure. Taking several months off—let alone years—for independent learning is really hard to explain to people. I know this from firsthand experience. During my 20s, I spent a year learning Chinese in China, mostly through independent self-study with an occasional personal tutor. Though my progress was much faster than when I went to a language school, self-study evoked considerable scepticism. Signalling was not a factor because any employer who cared about my language ability would just rely on standardised language exams and/or a job interview. Yet I still felt the social pressure to show I was using my time somewhat “productively”—and I’m already less susceptible to social pressures than most.

Overall, I think college is popular because it’s a socially acceptable and enjoyable way to spend a few years finding yourself. College assures anxious parents that their kids are being somewhat productive when they’re fresh out of high school with no clue what to do with their lives. I also know many people who did a Masters partway through their careers as a bit of a break or, in one woman’s words, an “expensive vacation”. Most don’t regret it, even though the financial returns were poor. They enjoyed their vacations.

Non-conformity is the way out

If signalling only accounts for 8% to 35% of the earnings premium, college isn’t a great conscientiousness signal, and employers don’t really value conformity, this is great news. It suggests we can get out of the zero-sum signalling trap.

Natural non-conformists could seek out alternative ways to signal their cognitive ability and conscientiousness. The more people—particularly Excellent and Good Students—that choose to do these things, the better these alternative signals will become. As it stands, Caplan’s arguments actively discourage non-conformists from trying this. If Caplan is correct, Excellent, Good and most Fair Students should selfishly go to college and shouldn’t bother to seek out more socially valuable signals.

To be clear, I still think college is a safe bet for the majority of students. Even after controlling for ability bias, Caplan’s selfish return calculations still show pretty good returns. But if you’re naturally self-motivated and non-conformist, you may well find better ways to level up your skills and signal your competence. Just don’t take the (ironically named) Case Against Education convince you that college is more valuable than it actually is.

Conclusion

To summarise this post:

- Caplan overstates the case for signalling by conflating ability bias and signalling.

- Ability bias provides a stronger case to reduce government funding than signalling does.

- This distinction between ability bias and signalling is important because signalling is a zero-sum competition for relative status. If Caplan is correct, education’s position is entrenched and cutting government spending won’t help.

- Luckily, signalling is nowhere near the 80% share that Caplan claims. Once you separate out ability bias, Caplan’s signalling estimate drops sharply to between 8% and 35%.

- Caplan provides no evidence that employers value conformity. A lot of people go to college, but that’s because it’s a socially acceptable way to spend a few years and most people are conformists.

- The best way to get out of the education signalling trap is by for natural non-conformists, especially competent ones, to seek out alternative signals.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post. Let me know what you think of my arguments in the comments.

Click here for my third and final post which scrutinises Caplan’s spreadsheets and assumptions.

If you still want to buy The Case Against Education, you can do so at: Amazon <– This is an affiliate link, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through it. Thanks for supporting the site! 🙂

See also:

- Book Summary: The Case Against Education by Bryan Caplan

- Criticisms of “The Case Against Education” (Pt 1 — it’s The Case Against Higher Education)

- 1(Added to clarify in response to a comment below: Overall spending on education would presumably fall but, since education is not 100% status, there’s no particular reason to think overall spending on status would drop. And I don’t think we’d be any better off to the extent the education spending is simply replaced by spending on other forms of status.)

- 2Based on subtracting the 25% and 45% ability bias estimates from the 33% and 80% estimates (respectively).

- 3Admittedly, I only know of people who already had a college degree and work experience using online credentials to change career paths. But that’s probably because I live in a bubble and know very few non-college grads, period.

4 thoughts on “Criticisms of “The Case Against Education” by Bryan Caplan (Pt 2 — Inflated Signalling Estimates)”

A lot of that makes sense but I think one bit is wrong, or if it’s not I’m failing to see the chain of logic.

In this part: “If Caplan is correct, cutting government spending would not solve the problem. Signalling is a zero-sum competition for relative status. While I agree that governments shouldn’t fund zero-sum competitions, eliminating government subsidies won’t eliminate the underlying competition. Education would still send a valuable signal. Any government savings returned via tax cuts could just be spent on more education. Dollars may move from the “public” column of the ledger to “private”, but there’s not much reason to think that overall spending on status would fall.”

I think that last sentence is wrong. I think we would expect more resources to be spent by society on relative status games when the government subsidises them, vs a situation where they don’t.

That is, if the government is going to tax everyone and then subsidise a status game, it makes sense for individuals to do more of the status game.

Let’s think of the total cost of education being the public contribution and the private contribution. The private contribution is the private cost.

The private cost of education is (total cost – public contribution). Their private benefit remains the same. They consume up until (public cost – subsidy) = private benefit.

If we eliminate the public contribution, the private cost = total cost. Their private benefit is again the same. They consume up until private cost = private benefit. It’s still a zero sum game, but so long as they have alternative goods and services (or alternative status games) to consume, their is less resources devoted to this particular status game.

Is that wrong?

If we elimate the subsidy

Two questions:

1.”They consume up until (public cost – subsidy) = private benefit.” – do you mean “They consume up until (total cost – public contribution) = private benefit”? If not, I’m not quite sure what (public cost – subsidy) refers to. Isn’t the subsidy the same as public cost?

2.”Their private benefit remains the same.” – I’m not sure about this assumption. It makes sense if education increases human capital, but I’m not sure it holds to the extent education is signalling. In the latter, the private benefit should fluctuate depending on what other actors do, so your model needs at least 2 private actors.

I’m envisaging a Prisoner’s Dilemma situation where each actor is incentivised to spend on education regardless of what the other does (but they’d both be better off coordinating and avoiding those wasted resources). So I think the Nash equilibrium point would depend on how much “spare” resources those actors had to spend on relative goods. If they both got a windfall tax cut, each person’s “spare” resources would just go up.

That said, I think you’re right to question the last sentence. I wasn’t fully sure of it either because, as you point out, there are alternative goods and services to consume. I expect the impacts will differ depending on how the tax savings are distributed – if the tax cut went to rich folks, it seems more likely to go back to education spending (or other relative goods) whereas poor folks are more likely to spend their savings on non-relative goods like food. But even then, I expect a considerable chunk to go towards land/education since much of the poverty in the US today is about inadequate housing and job opportunities rather than literal starvation (at least that’s my impression).

Also agree with your point that the money could be spent on alternative status games, hence why I said “overall spending on status” rather “overall spending on education”. But bear in mind that education is partly zero-sum (signalling) and partly positive-sum (human capital). So while overall spending on status would fall if the tax cuts went towards goods with a greater positive-sum component, it could also rise if the tax cuts were spent on goods with a greater zero-sum component. I don’t know which way things will cash out.

All this gets quite complicated which is why I said “not much reason” rather than “no reason” to try and signal my uncertainty, though perhaps I should have clarified it better in a footnote.

Sorry!

You’re right, I meant “They consume up until (total cost – public contribution) = private benefit”.

And I also think you’re right that in relative status games other people’s behaviour matters a lot, so the outcome will be complicated, but I think that so long as the government is reducing a subsidy to a relative status game, we would expect people to consume less of it.

I think the marginal propensity to consume education is what we’re after if we’re thinking about how much would still be spent on education with a tax cut funded by cutting public subsidies. It’s not going to be zero, but it’s also going to be nowhere near 100%?

Yup, agree that consumption of education will fall without subsidies. I just don’t know either way whether overall spending on status will fall.