Originally intended to be a workbook, How to Decide is intended to be more practical than Annie Duke’s earlier book, Thinking in Bets. Overall I think Duke achieves that, though How to Decide comes off a bit too simplistic for the real world.

Buy How to Decide at: Amazon | Kobo (affiliate links)

Key Takeaways from How to Decide

- A good outcome may be the result of a bad decision, and a bad outcome can be the result of a good decision. You shouldn’t confuse the outcome with the quality of the decision – that’s called “resulting”.

- Resulting, and other cognitive biases such as hindsight bias and motivated reasoning, get in the way of correctly assessing our past decisions. We need to get around these biases to learn from our past decisions and make better ones in the future. Ways to do so include using a Knowledge Tracker or Decision Tree.

- To make better decisions, you need a good decision tool. A pros and cons list is not a good decision tool because it is “flat” and tends to amplify, rather than mitigate, biases.

- Duke suggests a 6-step process for making better decisions. The key steps are to identify all the reasonably possible outcomes, identify your preferences for each outcome, and estimate each outcome’s probability.

- When estimating the probability of an outcome:

- Use an explicit percentage rather than natural language. Natural language is vague and people differ as to what terms like “real likelihood” means. An explicit percentage will help uncover disagreement and therefore get better information.

- Use a range to express your level of uncertainty. The correct answer should fall in your range about 90% of the time (not 100%).

- Start from the outside view and combine it with the inside view. An outside view is more objective and less likely to be biased. You can start from the outside view by taking a base rate (if available) or finding out what other (disinterested) people think.

- There is a trade-off between time and accuracy. Sometimes it’s not worth spending a lot of time analysing decisions and you can sacrifice accuracy to save time. Such situations include:

- Low impact decisions – use the Happiness Test to figure out if a decision is low impact. The Happiness Test asks how likely that decision will impact your happiness in a week, month, or year from now.

- Repeating decisions, as you’ll get another shot at the decision soon.

- Freerolls – where the potential upside is high but the potential downside is low (but you have to consider the cumulative downsides – a donut is not a “freeroll”).

- Close decisions – where either option is similarly good or bad.

- Decisions with low costs of quitting. If your decision comes with high costs of quitting, consider if you can decision stack (e.g. try before you buy).

- Parallel decisions – decisions that you can execute at the same time.

- Even if a decision is worth spending time on, there will be a point where you have to stop analysing. That point comes when any information that would change your mind either (1) cannot be gotten or (2) would be too costly to get.

Detailed Summary of How to Decide

Why you should care about making better decisions

- Two things determine how life turns out – luck and the quality of your decisions. You can’t affect luck, but you can affect the quality of your decisions. By improving the quality of the decisions, you increase the odds of good things happening to you.

- The future is inherently uncertain, so good decisions cannot guarantee outcomes. They just make good outcomes more likely.

Correctly assessing the quality of past decisions

- People generally find it hard to distinguish a good quality decision from a decision that turned out well. Instead of assessing the decision-making process, they just tend to look at the result of the decision. Psychologists call this “outcome bias” but Duke prefers the term “resulting”.

- The idea that the result of a decision tells you something about the decision’s quality is extremely powerful, but wrong. If you describe a situation to someone, their view of whether the decision is good or bad usually changes depending on what they know about how the decision turned out.

Example – Star Wars

Star Wars had been passed over by many film studios before being made. Obviously, it turned out to be an enormous hit. The general consensus is that film studios that passed it over (United Artists, Universal and Disney) made a bad decision in doing so.

But that’s resulting. We don’t know what the decision looked like when Lucas pitched Star Wars to these studios. It’s quite possible that Star Wars could’ve flopped. People infer the quality of the decision from its outcome, but you can’t do that based on a single result.

- For any single decision, a good quality decision can turn out bad and a bad quality decision can turn out good. This is because luck plays a role. In the long run, however, higher quality decisions are more likely to lead to better outcomes.

- The paradox of experience is the idea that experience is necessary for learning, but individual experiences often interfere with learning. This is because of various cognitive biases that hinder our ability to view decisions accurately.

Biases that get in the way of correctly assessing past decisions

Resulting, hindsight bias, and motivated reasoning

- Resulting (outcome bias) is when you judge a decision’s quality based solely on its outcome. This bias causes you to overlook the role that luck plays and will make you learn the wrong lessons.

- It can cause you to mistake a good outcome for a good decision or vice versa.

- It might make you less likely to assess your decisions when the decision quality aligns with its outcome (i.e. a good decision turns out well). Duke argues that there are still learning opportunities in such cases.

- An outcome can still be informative if it is unexpected. An unexpected outcome suggests that there was something you failed to take into account, which you should next time.

- Most people are likely to blame bad luck for a bad outcome and credit skill for a good outcome. This is motivated reasoning. Motivated reasoning is the tendency to process information to get to the conclusion we want (rather than the truth). Motivated reasoning might be comforting, but it hinders your ability to learn from your experiences and make better decisions. In the long run, you can make better decisions if you’re accurate in how you perceive the world.

- Hindsight bias is the tendency to believe that the way something turned out was inevitable or at least predictable. People often say “I should have known” or “I can’t believe I didn’t see that coming”. Hindsight bias can distort your memory of what you knew at the time you made the decision.

- Resulting and hindsight bias can also make you less compassionate. It can make you more likely to blame people for bad outcomes even when the bad outcome wasn’t their fault.

- Memory creep occurs when what you know after the fact creeps into your memory of what you knew before the fact.

Other cognitive biases

Other cognitive biases that Duke mentions briefly, but does not focus on, include:

- Confirmation bias – the tendency to notice and seek out information that confirms our existing beliefs.

- Disconfirmation bias – the tendency to be more critical of information that contradicts our existing beliefs.

- Overconfidence – overestimating our own skills, intellect or talent.

- Availability bias – overestimating the frequency or likelihood of events that are easily available. For example, more vivid events are easier to recall, so are more available.

- Recency bias – believing that recent events are more likely to occur than they actually are. [This seems to be a sub-type of availability bias.]

- Illusion of control – overestimating our ability to control events and underestimating the role of luck.

How to get around these biases

Use a Knowledge Tracker

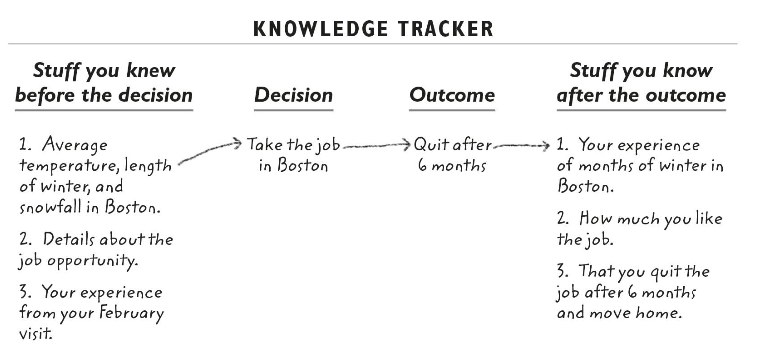

- Duke suggests using a Knowledge Tracker to record what you knew before the decision, so that you can later compare it with what you knew after it. [What if you didn’t really “know” something but you assigned a probability to it. How do you know if that assigned probability was correct?]

- A Knowledge Tracker reduces hindsight bias as it clarifies what you did and didn’t know at the time of the decision.

Draw a decision tree

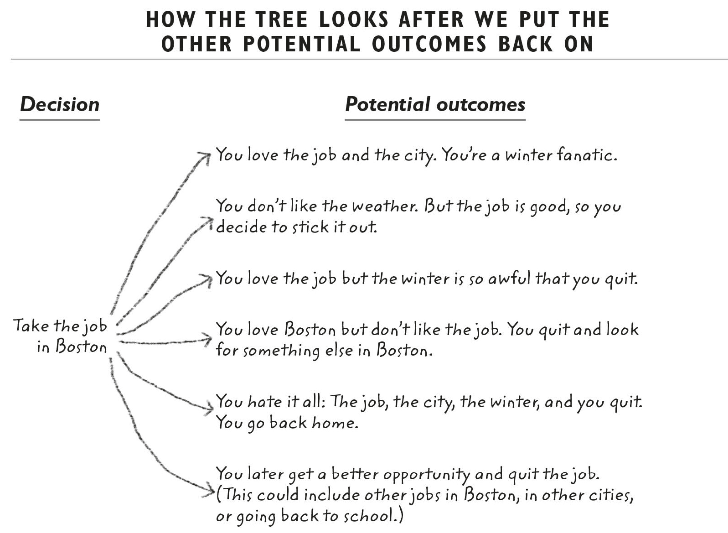

- A decision tree is a useful tool for evaluating past decisions and improving the quality of new ones.

- Before a decision, the different potential outcomes of that decision are like the many different branches of a decision tree. There are many possible futures but only one past. Once the outcome of a decision is known, resulting and hindsight bias causes us to mentally “chop off” all those other branches that never happened.

- You should try to put the tree back together so that you can see the outcome in its proper context. You should consider the counterfactuals – i.e. outcomes that could have happened, but didn’t. The counterfactuals will put the actual outcome into context, helping you understand how luck might have played a role and reducing the feeling of inevitability.

- Naturally, we are more willing to consider counterfactuals when we fail than when we succeed. But you should consider counterfactuals even when you succeed because those decisions are also learning opportunities. Luck could have played a role there, too.

- If you drew a decision tree before making the decision, even better! A tree drawn beforehand will more accurately represent what you knew before the decision than one drawn retrospectively.

Making better decisions

Improving your decision-making involves being better at predicting a set of possible futures. The future is inherently uncertain, which poses a challenge. Duke suggests 6 steps to better decision making. [Most of the book focuses on step 3, probably because of Duke’s background as a poker player. I wish she had spent a bit more time on steps 1 and 2, though. Step 2 in particular is harder than Duke makes it sound and I suspect pros and cons lists are used to help with that step. ]

1. Identify the reasonable set of possible outcomes

“Reasonable” is the key word here. You don’t have to try and account for every possibility. Some outcomes are so unlikely it’s not useful to include them in your decision process.

These outcomes can be general scenarios or more focused on particular aspects that you care about. For example, if you’re hiring an employee and the most important thing to you is staff turnover, your possible outcomes could be whether they will leave in < 6 months, between 6-12 months, between 1-2 years, etc.

2. Identify your preference using the payoff for each outcome

That is, to what degree do you like or dislike each outcome, given your values? This is a personal question that can vary between individuals. The simplest way to do this is to list potential outcomes on the tree from most preferred to least.

You should also think about the size of each preference – i.e. how good or bad is each outcome? If you don’t consider the size of the payoffs, you can’t figure out if going for a potential upside worth risking the potential downside. Size is easy to measure when the payoff is in money, but harder if it’s something else (e.g. happiness, prestige.

3. Estimate the likelihood of each outcome unfolding

It’s important to make an estimate, even if you’re unsure

Most people are uncomfortable estimating the likelihood of something happening in the future because they don’t like being wrong. Since you don’t have perfect information, you can’t give an objectively perfect answer.

Duke argues that thinking there is only “right” and “wrong”, with nothing in between, is one of the biggest obstacles to good decision-making. You almost always know something that is relevant to assessing the probability, and something is better than nothing. Even if you don’t hit the “bullseye”, being a little less wrong is still valuable. You get points for being on the board, even if you don’t hit the bullseye.

An advantages of explicitly making an educated guess is that it makes you think more carefully about what you do know, and what you can find out, to try and make a better guess. When you make a decision, you’re implicitly making a guess about how things will turn out anyway. So better to be explicit about it so that you can bring any accessible and relevant information to bear on the decision.

Use an explicit probability rather than an ambiguous term

If you’re not comfortable expressing an explicit probability (e.g. 45% or 70%), you can start by using natural language terms instead (e.g. “likely”, “more often than not”, “rarely”).

However, these terms are very ambiguous and blunt. In a survey of 1,700 people, Mauboussin and Mauboussin found that people differed enormously in what they meant by various terms. For example, some thought “real possibility” meant 20% chance while others thought it meant 80%. That ambiguity is part of why people like to use such terms – so they can avoid being “wrong”. You can take the Mauboussin survey for yourself here.

[One weakness of the Mauboussin survey is that it requires you to give an exact percentage. But I think most people do envisage a range, rather than an exact percentage, when they use natural language terms. For example, I think “unlikely” could mean anything from around 5% to 40%. The survey responses for “unlikely” ranged between 5% to 35%, which is actually pretty close to what I mean when I use that term. Would be interesting to see what the results would be if people could give ranges to each of these terms. ]

But if you want to be a better decision-maker, such ambiguous terms are harmful. One way to make higher quality decisions is to get more information – often from other people. If you use ambiguous terms with other people, it’s harder to uncover disagreement. Precision uncovers disagreement, and disagreement helps you get relevant information. For example, say you think something has around a 30% chance of happening, and your friend thinks it has a 70% chance. If you tell them you think it has a 30% chance of happening, your disagreement is revealed immediately. Your friend can then tell you why they think there is actually a 70% chance. Whereas if you just say you think there’s a “real possibility” of it happening, your friend may just nod and agree with you. Basically you want to know when you’re wrong, and ambiguous terms make it harder to be wrong.

Example – Plan to overthrow Fidel Castro

President Kennedy approved a plan to overthrow Fidel Castro because his military advisors told him the plan had a “fair chance” of success. The plan ended up being a pretty bad failure.

By “fair chance”, the advisors had meant around 25%. But Kennedy approved the plan, thinking “fair chance” meant a much higher probability.

Use a range

Once you’ve made an estimate of the likelihood of each outcome, it’s important to be clear about how uncertain your estimate is. A good way to do this is to offer a range alongside your estimate.

The purpose of a range is to signal, to yourself and to others, how uncertain you are of your guess. By expressing your uncertainty, you are implicitly inviting others to offer up information that can help improve your estimate. [I also think one advantage of using a range is that it forces you to be more careful, and think harder, about the probabilities.]

A wide range is not a bad thing. It just signals that you’re less certain in your estimate – that’s better than overselling your level of certainty. At the same time, your range should only include the lowest and highest reasonable values, not the lowest and highest possible values. If you’re aiming for a range that is guaranteed to include the correct answer, your range will probably be too wide to be informative.

So you have to strike a balance between being overly certain (narrow range) and overly uncertain (wide range). Duke suggests aiming to set the narrowest range you can, where you would still be “pretty shocked” if the correct answer wasn’t in the range. She suggests aiming for the correct answer being inside the range 9 out of 10 times (not at least 9 out of 10 times, which would encourage you to set overly wide range).

Most people are overconfident in their guesses. To assess if that’s true for you as well, take this quick shock test. To guard against overconfidence and question your beliefs more, make it a habit to ask yourself, “If I were wrong, why would that be”? This habit can also encourage you to go and try to find out information that would

Combine the inside view and the outside view

Inside view

Most people feel like they are better at solving other people’s problems than their own. This is because when you’re considering your own problems, you’re trapped inside the inside view.

The inside view is the view of the world from inside of your own perspective, experiences and beliefs. When you make a decision based on your intuition or gut feel, that is taking the inside view. That view makes it hard to see your opinions, experiences and beliefs objectively. Our beliefs form the fabric of our identity, and we are motivated to protect those beliefs. But if you don’t have a clear view of your skill level, you can make some pretty bad decisions.

For example:

- On their wedding day, most couples would probably take the inside view and assume the chances of them divorcing is close to 0%. They’ll focus on their specific relationship and its strengths and weaknesses in assessing the likelihood of a divorce, and ignore how common divorces generally are.

- About 90% of Americans rate their driving ability as above average.

- Only 1% of students think their social skills are below average.

Being smart doesn’t make you less susceptible to the inside view. If anything, it makes it worse for several reasons:

- Smart people are better at motivated reasoning – they are more able to interpret information to confirm their prior beliefs.

- Similarly, smart people are better at constructing arguments that support their views, and convincing people around them.

- Smart people also tend to have more confidence in their intuition or gut. Because of that overconfidence, smart people are less likely to seek feedback.

Outside view

In contrast, the outside view is what is actually true of the world, independent of your own perspective. It’s how someone else would view your situation. Getting other people’s perspective is helpful not just because they may have information you don’t have, but also because they may take a different view of the same facts that you have.

Duke thinks that many cognitive biases, including resulting and confirmation bias, are inside view problems – at least in part – as they give your own experiences and beliefs disproportionate weight. To overcome those biases, taking the outside view is helpful. The outside view may be uncomfortable, but it will improve the quality of your decisions.

Some ways to get to the outside view:

- An easy way to get to the outside view is to find out the base rate if available. A base rate is how likely something is to happen in situations similar to the one you’re considering. For example, to assess the likelihood of your marriage ending in divorce, the divorce rate in your country may be a good base rate.

- Another way to get to the outside view is to find out what other people know. Simply asking people for their opinions often isn’t enough because most people dislike conflict so are reluctant to disagree. We also tend to seek out views from people who are likely to agree with us, and therefore end up in an echo chamber. You should therefore act in a way that invites people to give you an outside view, and be thankful when people disagree with you in good faith. Such people are helping you by giving you a different perspective. It might be tempting to shield yourself from disagreement because it feels bad in the moment, but uncovering that disagreement has the power to improve your future decisions.

- Ask yourself what your view would be if a co-worker or friend approached you with this same problem.

- Keep a journal of the outside view and the inside view. Duke calls this Perspective Tracking. This will help you get better feedback about how you thought about your decision. As the future unfolds and your perspective changes, you will have a record of how it changed, which will create a higher quality feedback loop for improving decision-making.

Combining the two

Accuracy lies in the intersection of the outside and inside views. It’s helpful to start with the outside view or base rate, since it reduces the distortions of the inside view. However, the inside view can still have some information that is relevant to your particular case.

So you should combine the outside view with the inside view. The inside view may have information to suggest that your chances are better or worse than average. But the outside view is a useful reality check. If you learn you’re planning on doing something with really bad odds, knowing those odds can encourage you to identify possible obstacles and come up with ways to overcome them to improve your chances of success.

4. Assess the relative likelihood of outcomes you like and dislike for the option under consideration

Once you’ve combined probabilities with your preferences for each payoff/outcome, you will be able to evaluate and compare options more clearly.

5. Repeat steps 1-4 for other options under consideration

6. Compare the options to one another

Pros and cons lists are not good decision tools

- A pros and cons list is not really designed as a tool to help you compare choices, but rather as a tool to help you evaluate a single choice.

- Duke thinks the biggest issue with a pros and cons list is that it is formed from the “inside view” and therefore amplifies cognitive biases. When you want to accept an option, you’ll focus more on the “pros”. When you want to reject an option, you’ll focus more on the “cons”. A pros and cons list therefore gets you to the decision you want to make rather than the decision that is objectively better. In contrast, a good decision tool should reduce such biases.

- One good thing about a pros and cons list is that it at least gets you thinking about the potential upsides and downsides. But the problem is that it doesn’t get you thinking about the magnitude or size of the payoffs. [You can always do a weighted pros and cons list, instead of just comparing the number of “pros” vs “cons”.]

- A pros and cons list does not include information about the likelihood of each pro or con occurring. [Maybe, but if I thought a pro was unlikely to materialise I’d probably give it less weight on the list.]

Getting feedback from others

- Beliefs are contagious. If you tell others what you think when asking for feedback, their feedback is likely to mirror your own views. Keeping your views to yourself makes people more likely to tell you what they really think.

- Outcomes are also contagious. If you tell people what happened when asking for feedback, it can ruin their feedback because it makes resulting likely. You’ll get better feedback if you tell them only as much information as you had at the time you made your decision.

- Try to be neutral in the way that you frame your questions to others. The way you present information to others can influence the way they react to that information.

- Use a neutral term like “diverge” instead of “disagree” to describe when people’s opinions differ. This will help you embrace disagreement.

Checklists are useful for getting feedback

- Make a checklist of details that someone would need to know in order to give you high-quality feedback and then give them those details. This is particularly useful for repeating decisions because you can think about it before considering an individual instance of a decision.

- What the checklist contains will differ depending on the type of decision but it should always include what you want to accomplish as people’s goals and values will differ.

- It’s important to agree that people participating in the feedback process is accountable to the checklist. Otherwise, someone might assume that if details are emphasised, it’s because they’re important, or if a detail is missing, it’s because it’s unimportant.

- Real accountability to the checklist means that if someone can’t provide the details required to give high quality feedback, you shouldn’t give it. For example, Duke wouldn’t give students feedback on how they should have played poker hands if the students couldn’t tell her the size of the pot. This made the students pay closer attention to the size of the pot, and helped them understand why the size of the pot was so crucial.

Deciding when to optimise decisions

- Time is a limited resource. Therefore it is important to be able to distinguish when which decisions are worth spending more time on, and which ones are not.

- There is a trade-off between time and accuracy. Increasing the accuracy of a decision costs time, but saving time costs accuracy.

- Duke argues that the 6-step decision framework above helps manage the time-accuracy trade-off because it gets you thinking about upside/downside potential and therefore impact.

- Low impact decisions are a good opportunity to take risks and “poke at the world”, which can help you learn about the world and your own preferences.

- One reason people can be indecisive even about low impact decisions is fear of regret. Regret is a short-term cost of a bad outcome, even when a decision doesn’t affect your long-term happiness. Anticipating regret can induce “analysis paralysis”.

The Happiness Test

Duke suggests using the Happiness Test to figure out whether a decision is low impact. Happiness is a good proxy for understanding the impact of a decision on achieving long-term goals.

The test involves asking yourself if the outcome of the decision will likely have a significant effect on your happiness in a year, month or week. The shorter the time period for which your answer is “no”, the quicker you can make that decision (sacrificing accuracy).

Repeating decisions

If a decision repeats, you can trade-off accuracy because you’ll get another shot at the decision soon. A repeating decision helps reduce the impact of regret. For example, if you ordered a bad lunch option, that’s okay because you’ll eat again in a few hours. [That’s assuming a second chance at the option can somehow “undo” or at least reduce the negative consequences of the first decision, though. Some decisions aren’t like that – e.g. if you go free soloing every day and make a bad decision, that bad decision could kill you. The fact that the decision is a repeating one doesn’t help reduce its impact at all.]

When making a decision that repeats, you can afford to be a bit more adventurous (e.g. trying a new food or TV show). With such decisions you can get information about your likes and dislikes at small cost.

Freerolls

Freerolling describes a situation where there is an asymmetry between the upside and downside because the potential losses are insignificant. The limited downside means there is not much to lose – but potentially much to gain.

Once you identify a freeroll opportunity, you don’t need to think much about whether to take that opportunity, but you may still want to take time with executing the decision. For example, you might decide to apply to your dream college even if you have low chance of getting in because the application costs are relatively low and the upside is so high. But you still want to take your time with the college application. [I kinda disagree that this is a freeroll opportunity. Is the asymmetry really in your favour if the probability is that low? It seems like it would be better to factor in probabilities and consider the *expected value* of a decision, rather than purely its potential upsides and downsides. Duke spent so much time discussing probabilities in her 6-step process, it’s very odd she just ignores them here.]

The fear of failure or rejection can cause you to pass on great freeroll opportunities, especially when the likelihood of failure is so high. Duke argues against this, as the potential downsides are just small and temporary.

Cumulative downsides

When considering if a decision has limited downside potential, it’s important to think about the cumulative effects of making the same decision repeatedly.

For example, if you’re trying to eat healthier, each donut can look like a freeroll. After all, one donut has a minimal impact on your overall health but you can get a lot of enjoyment from it. If you look at the cumulative impacts of eating donuts or other unhealthy foods though, it’s a different story.

Duke points to the lottery as an example that is not a freeroll, because, in the long run, the losses outweigh the potential gains. [I don’t find this argument convincing. I think a better argument against the lottery being a freeroll is my expected value argument above.]

Close decisions are easy

Sometimes we have trouble deciding between two options that seem very close to each other in quality. Duke calls these decisions “sheep in wolf’s clothing”. Even if such decisions are high impact, Duke argues that the closeness is a signal that you can make the decision faster and worry less about accuracy. After all, the payoffs are similar. Reframe the decision by asking, “Whichever option I choose, how wrong can I be?”

We live in a world of imperfect information so, when two options are very close in quality, it’s unlikely that you can work out which option is better even by taking more time.

In The Paradox of Choice, Schwartz pointed out that more choices are more likely to induce analysis paralysis. Two strategies to use when you’re deciding between close options are the only-option test and the menu strategy:

- The Only-Option test asks, “If this were the only option I had, would I be happy with it?” For example, if this were the only thing I could order on the menu tonight, would I be happy with it? If the answer is yes, go for it, and don’t worry about the fact that a better option may have been available.

- The Menu Strategy says to spend your time on the initial sorting, and save your time on the picking. Despite its name, the strategy can be used for decision-making more broadly. Sorting is the part of the decision making process that gets you big gains – figuring out, based on your values and goals, which options are “good”. Then you can just pick among the good options without trying to distinguish further between them.

Know the costs of quitting

Quitting gets a bad rap. When you make a decision, you’re doing it with limited information. As things unfold, you may get new information. That new information reveal that another option is better.

There are, of course, costs to quitting. Part of a good decision-making process involves factoring in the costs of quitting. The lower the cost of quitting, the faster you can make decisions because it makes it easier to change course partway through as you get more information. When the cost of quitting is low, that can also be an opportunity to experiment and learn more about the world or your own preferences.

If you have a high impact decision with high costs of quitting, try decision stacking.

Decision stacking is finding a way to make low-impact, easy-to-quit decisions before you make a high-impact, harder-to-quit decision. For example, you’ll date someone before you decide to marry them. Each date is a low-impact decision that gives you more information to make a high-impact one.

Parallel decisions

When you can choose multiple options in parallel, the opportunity costs are lower because you get the upside potential of multiple decisions at once. Parallel decisions can also lower your exposure to the downside potential. For example, you can order multiple dishes at a restaurant. You increase the chances of ordering a great dish and reduce the chance that you’ll have to eat something you don’t like.

But it comes at a cost. Ordering multiple dishes, for example, obviously costs more than ordering one. And if you’re trying to do more than one thing at once, you may face constraints (e.g. in time or attention) in trying to execute them all at once.

When to stop analysing

- You have to accept that you’ll never get certainty about your decisions. Chasing uncertainty causes analysis paralysis.

- Ask yourself if there’s information that you could find out that would change your mind.

- If the answer is “no” – stop. You’re done.

- If the answer is “yes” – ask yourself if the information is worth getting. Some information may be too expensive to get. If it’s worth getting, get it; if not, just make your decision without that information.

- Duke refers to the concept of maximising vs satisficing based on The Paradox of Choice by Barry Schwartz.

- Maximising is trying to make the “optimal” decision. It involves examining every possible option and trying to make the perfect choice. Most people have maximising tendencies, but Duke warns against it as there’s no such thing as a “perfect” decision when information is imperfect.

- Satisficing is when you just choose the first satisfactory option available. The term is made up by combining the words “satisfy” and “suffice”. Duke says her strategies are designed to get you more comfortable with satisficing.

Execution problems

- There’s a big gap between what we know we should do and what we actually do. Carl Richards, a financial planner, described this as the behaviour gap.

Power of negative thinking (planning)

- Negative thinking is important. Not so much thinking “I am going to fail”, but thinking “If I were to fail, how might that happen?”

- Imagining how you might fail doesn’t make failure more likely. In fact, it’s been shown that mental contrasting, where you imagine what you want to accomplish and the obstacles to achieving it, can help you achieve your goals.

- Gabriele Oettingen, a professor of psychology, found that in a weight loss program, those who imagined how they might fail lost on average 26 pounds more than those who just did positive visualisation. She has found similar results in other areas including getting better grades, finding a job, or asking out a crush.

- One reason negative thinking can be helpful is that it may allow you to hedge. A hedge is something that reduces the impact of bad luck, but which you never want to use. An insurance policy is a classic example. But hedges are costly so you may not always choose to hedge against risk.

Mental time travel

- Prospective hindsight means imagining yourself at some point in the future, having succeeded or failed at a goal, and looking back at how you got there. Looking back from an imagined point in the future can improve your ability to see past what’s directly in front of you.

- The Happiness Test is an example of mental time travel.

- The key is that you’re not just imagining success and failure, but identifying the paths that led you there. Premortems and backcasting are two tools that help you do this.

Premortems

- Since a post-mortem happens after the fact, their benefits are limited to lessons for the future.

- A premortem is when you imagine yourself at some point in the future, having failed at your goal, and looking back at how you got there. The idea was coined by psychologist Gary Klein.

- Duke suggests the following steps to conducting a premortem (adapted from Gary Klein):

- Identify the goal you’re trying to achieve or a specific decision you’re considering.

- Figure out a reasonable time period for achieving the goal or for the decision to play out.

- Imagine it’s the day after that time period and decision worked out poorly. Looking back from that imagined future point, list up to 5 reasons why you failed due to things within your control.

- List up to 5 reasons why you failed due to things outside your control.

- If you’re doing this as a team exercise, get team members to do steps 3 and 4 independently before discussing together as a group.

- This exercise can produce more reasons for why something might fail. When applied in teams, it can also reduce groupthink by encouraging different points of view.

- Since a premortem identifies places where bad luck may intervene, you can use that to look for ways to hedge that bad luck.

Backcasting

- Backcasting is like a premortem, with the difference being that you imagine you succeeded at your goal. The steps for a backcasting are largely the same as for a premortem.

- Imagining a positive future comes more easily to most people than imagining a negative one. For this reason, Duke suggests starting with a premortem and anchoring there. A premortem reduces our natural tendency towards overconfidence and the illusion of control.

- Once you’ve done these exercises, consider:

- Do you want to modify your goal or change your decision, given what you’ve just learned?

- Are there ways to modify your decision to increase the chances of good stuff happening and decrease the chances of bad stuff happening?

- Plan how you’ll react to future outcomes so they don’t take you by surprise.

- Look for ways to mitigate the impact of bad outcomes.

Tips for self-control problems

Precommitment contracts

A precommitment contract, also known as a Ulysses contract, is an agreement that commits you in advance to take or refrain from taking certain actions, or raising or lowering barriers to those actions. A contract can be with another person, or even with yourself. For example, if you want to wake up earlier you can set your alarm and put it on the other side of the room, increasing the barrier to hitting the snooze button.

The Dr Evil Game

Dr Evil makes you fail by making small, poor choices that can be justified when considered individually. However, when considered cumulatively, the decisions will make you fail – and you won’t even notice.

To play the Dr Evil game:

- Imagine a positive goal.

- Imagine that Dr Evil has control of your brain, causing you to make decisions that will guarantee failure.

- Any given instance of that type of decision must have a good enough rationale that it won’t be noticed by you or others examining that decision.

- Write down those decisions. The point of the Dr Evil game is to identify entire categories of decisions that will cause you to fail. Then you address them in two ways:

- First, you need to appreciate that these types of decisions require special attention. You need to approach them more deliberatively and less reflexively.

- Second, you can make a category decision to take those choices out of your hand. A category decision is a one-time, advance choice about what options you can and cannot choose. For example, deciding to be a vegan is a category decision as you no longer need to decide whether to eat animal products at each meal. By making a category decision in advance, it saves you from having to make a series of decisions at moments when you may be tempted to follow your impulses.

The point is, you are Dr Evil. The reasons that Dr Evil comes up with are the ways you sabotage yourself.

Tilt

- Don’t make decisions immediately after a bad outcome. A bad outcome will activate the emotional parts of your brain and inhibit the rational thinking parts of your brain. This emotional state is called tilt.

- Instead, think about how things might go wrong in advance, and how you might respond to them. This reduces tilt by reducing the emotional impact the bad outcomes have when they do occur. You can also pre-commit to taking (or not taking) certain actions when faced with a bad outcome.

- Learn to recognise your signs of tilt. For example, is your face flushed? Do you use particular language?

- When you recognise the signs of tilt, ask yourself if you’ll be happy with your decision a week, month, or year from now.

- Unexpected good outcomes can also compromise your decision-making ability. Consider using the same tools to prepare for reacting to unexpectedly good outcomes as the ones for dealing with tilt.

Other Interesting Points

- A lot of people thought Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 election because she neglected Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Many commentators criticised her campaign for doing so – but only after the election results were known. Duke went 10 pages deep on Google and couldn’t find anyone suggesting Clinton should have focused more on those 3 States before the election. The swing States were thought to be Florida, North Carolina and New Hampshire, which is where Clinton was campaigning. People were actually questioning and criticising Trump for “wasting time” campaigning in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

- The average person spends 150 minutes a week deciding what they want to eat, 50 minutes deciding what to watch on Netflix, and 90-115 minutes deciding what to wear. [Surely this is self-reported and highly inaccurate, though.]

- The bestselling book, The Secret, claimed that your brain waves have a magnetic quality that makes positive thoughts attract positive things and negative thoughts attract negative things.

- The doctor who pushed for good handwashing practices, Ignaz Semmelweis, lost his job for doing so. He also lost two other jobs later where he introduced similar handwashing policies. Semmelweis died in an insane asylum at the age of 47.

My Thoughts

I liked the first half of How to Decide more, which focused on making decisions and estimating probabilities. The second half, which dealt with execution, mental time travel, etc, was weaker and less structured. You can also tell by Duke’s summaries being quite tight for most of the book and getting several pages long by the end.

It seems like most of the ideas in this book can also be found in Thinking in Bets. The main exception is probably the stuff on analysis paralysis. Overall, How to Decide is more succinct and practical, whereas Thinking in Bets is more of an interesting read. I don’t think you need to read both, and I’d recommend How to Decide as a more efficient read. Duke even summarises the key points at the end of each chapter and in a bunch of handy “checklists” at the end, which is very useful.

Some of the “decision hygiene” stuff is also similar to that contained in Noise by Kahneman, Sibony and Sunstein, so I didn’t summarise that chapter as carefully. Kahneman, Sibony and Sunstein’s advice is more detailed and persuasive, but seems intended more for leaders of large organisations. Duke’s advice is simplified more accessible and aimed at individuals.

I tried to do some of the exercises in the book as I went along, some of which were quite useful. The shock test was a real eye-opener and quite enjoyable – I’d recommend trying that. But some of the other exercises I found harder to do in practice than expected. For example, right at the start Duke asks you to identify some of your “best and worst” decisions. I found it difficult to even identify best and worst outcomes (which is what you’re not supposed to do), let alone my best and worst decisions. For example, I moved to a different city just over a year ago. Was that a good outcome? I think so, but I’m not sure. Overall I’m happy with my decision but there have been some downsides to moving as well.

Moreover, life is ongoing so it’s hard to know at any point if a decision was good or not. Even when I took a job that ended up making me miserable, I’m not sure I would say that was a bad outcome. My pay increased significantly at that job and I still learned a lot, and it helped me get into a much better job in less than 2 years.

Identifying my best and worst decisions (what Duke actually asked you to do) is even harder. Apart from minor decisions that I don’t tend to spend much time analysing, I tend to take the same basic approach to all major decisions. It’s not like I do a careful analysis of some major decisions and then do a shoddy analysis of other ones. My analysis is either generally careful or generally shoddy, depending on the significance of the decision. So it was hard for me to pick out some decisions as being of higher or lower quality than others.

I also found some of the exercises a bit too simplistic. One example Duke uses is when you quit your job to develop a new app-based business and get your friends and family to invest in it. In real life, lots of decisions are wrapped up in that “decision”. For example, maybe it was a good decision to quit your job but it wasn’t a good decision to keep persisting with it after making no traction for, say, 1 year. Or maybe the quitting your job was fine but it was your decision to try and do everything yourself and not outsource parts that was the problem, etc. I couldn’t help but wonder whether Duke applied her own advice to her life decisions, and suspecting not, because most (or all?) of her examples were hypothetical.

Buy How to Decide at: Amazon | Kobo <– These are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase. I’d be grateful if you considered supporting the site in this way! 🙂

Have you read How to Decide? Let me know what you thought of it in the comments below!

If you enjoyed this summary of How to Decide, you may also like these books about decision-making:

2 thoughts on “Book Summary: How to Decide by Annie Duke”

Wow! Really nice summary. Thank you madam or sir!

Unfortunately there is much more to read than I have time, so I really like to read some summaries first to decide whether I should go for the time investment. Such great summaries really help on that.

Thanks Stefan for your kind comment 🙂 Glad you found the summary helpful. Do you think you’ll read How to Decide?