In The New New Zealand, Spoonley discusses the demographic challenges facing New Zealand over the next few decades. The book tackles an interesting and neglected topic and its overall message (i.e. that there need to be informed, national discussions about this) seems sensible enough. Unfortunately, however, Spoonley’s writing isn’t great, and he relies too heavily on secondary sources.

Buy The New New Zealand at: Amazon | Kobo (affiliate links)

Key Takeaways from The New New Zealand

- Many countries – including New Zealand – face challenges of population stagnation or decline. New Zealand’s fertility rate is currently below the replacement rate of 2.1.

- Population stagnation and decline is caused by:

- Increased life expectancy – people are living longer on average; and

- Falling fertility rates.

- The only reason New Zealand’s population keeps growing is because of immigration. Immigration contributes around two-thirds of population growth, while natural growth contributes only one-third.

- However, immigration is not even across the country. Immigrants tend to go to the centres (particularly Auckland), not the regions.

- So the regions are in decline, while Auckland is thriving. As time goes on, the gap between Auckland and the rest of the country will get larger – in terms of age, diversity, and density.

- New Zealand will become an “aged society” in the late 2020s or early 2030s, with over 20% of its population aged 65 years or older:

- This is largely due to the baby boomer generation reaching 65. The retirement of the baby boomer generation is unprecedented – they are retiring healthier, wealthier and in bigger numbers than ever. The demographic changes ahead are unprecedented.

- As the dependency ratio increases, New Zealand has to have informed discussions about things like the affordability of superannuation and the availability of healthcare and other services for the elderly (particularly in the regions, where the working age population will shrink).

- There’s lots of “doom and gloom” in demography. We should also remember that the current challenges of an ageing society are the result of major health advances.

- The changing demography of New Zealand is not a crisis. There are choices around how to approach these changes.

- But doing so requires informed, national discussions about the changes and a population strategy. Unfortunately, most people don’t want to talk about it. In particular, talk of population “stagnation” or “decline” in the regions is very unpopular as it feels like defeatism. Spoonley thinks this inevitably has to change as the effects of stagnation and decline become more obvious.

- If New Zealand does not face up to these changes, it could become a crisis.

Detailed Summary of The New New Zealand

The Census

The New Zealand census has significant consequences for allocation of resources and policy decision-making. It’s important that the census continues in its current form, as it gives us the data to understand what is happening to the demography of New Zealand.

Unfortunately, the census has not always included Māori properly:

- The first census in 1851 only counted European settlers. Statistics about Māori were recorded in a separate process, with different questions about iwi/hapū and their degree of assimilation.

- It wasn’t until 1926 that Māori completed the census on the same night as everyone else.

Ethnicity in New Zealand

New Zealand records ethnicity in an interesting way:

- It is by self-definition, and people can pick more than one option. So the figures on ethnic identity add up to more than 100% (unless you’re looking at “primary” ethnic identity).

- “New Zealander” is an option. Spoonley calls this “a rather peculiar national response descriptor in a question on ethnic identity”, and thinks it is inappropriate as an ethnic response category. He also notes that its introduction created a number of consistency issues with previous censuses. In the 2006 census, “New Zealander” was the third most important ethnic category. Apparently late middle-aged New Zealand Europeans, from areas where they were dominant and where there was opposition to Māori rights claims, are most likely to use it.

Family and fertility trends

Fertility trends

Current fertility rates

The replacement-level fertility rate is 2.1. Many countries are now below this, particularly higher-income countries:

- The OECD average is 1.7.

- In Europe, the average is 1.6, but in some countries it is much lower.

- Asia’s rates are also very low. China’s is 1.5, Japan’s is 1.4, and Korea’s is 1.3. Below 1.5 is a “very low fertility country”.

- Sub-Saharan Africa still has relatively high fertility rates (around 4.7) but they have still been falling for most countries.

Fertility rates vary among ethnic groups. In New Zealand in the 2010s, fertility rates for Māori (2.6) and Pasifika (2.8) were higher than for New Zealand Europeans (1.7) and Asians (1.8). (They are still declining, though.)

Fertility rates have been falling globally, and in New Zealand

Fertility rates have been dropping over the last 200 years in developed countries, particularly since the 1970s:

- Before the Industrial Revolution, women probably had around 7 or more children (in part as insurance against high infant mortality).

- During the baby boom years, the fertility rate was around 4.0-4.5. It declined after the 1970s.

- Many things drove this drop in fertility. For example, increasing urbanisation, increasing education and workforce participation of women, higher costs of having children and changing cultural norms. The increased availability of contraception (around 1960s) and abortion has also had a big impact.

New Zealand’s fertility rate has been declining since the late-1900s:

- In the 1960s, the total fertility rate was 4.3. It fell below replacement levels by 2016. New Zealand’s fertility rate was 1.8 in 2017.

- UN projections suggest the New Zealand fertility rate won’t drop much more, but the current sub-replacement rate will still mean population stagnation or decline for much of the country.

Policies aimed at increasing fertility rates have little to moderate impact.

- Family-friendly policies (e.g. tax incentives, better childcare and parental leave) appear to work moderately well in some Nordic countries, but not at all in others like Germany.

- Most cases, natalist policies amount to throwing money at people who would have had children anyway. [This makes intuitive sense. It seems like those policies would remove or reduce barriers for people who wanted to have children anyway, but might not simply because of the costs. Yet the fact that fertility rates have declined more in high-income countries suggests that the cost of having children is not the main reason why fertility rates have fallen so much. Furthermore, natalist policies will never be enough to offset the entire cost of raising a child (including opportunity costs).]

- Migration is one of the few things that can actually impact declining fertility.

Decreasing fertility will create issues for future labour and skills supply.

Family formation trends

Not only are people having fewer children than before, they are also having children later:

- Compared to previous generations, boomers had children later, and had fewer children. These trends have persisted since then (the declining rate of marriage has stabilised, but at a much lower level).

- Currently, there are more children born to women over 40 than to teenagers.

Single-person, or sole-parent households have also been increasing:

- Boomers also married at a lower rate, and divorced at a much higher rate, compared to previous generations.

- Single-person households will be New Zealand’s most common household type in the 2020s. They are expected to make up 30% of all households by 2031.

- Sole-parent households have grown a lot over the last 50 years.

- Currently they make up around 30% of all family households [not 30% of “all households”] in New Zealand and is expected to grow further [Wow].

- Sole-parent households tend to have much lower incomes. In New Zealand, 75% of sole parents are not working and rely on benefits (compared to the OECD average of 61%).

Childless households have also increased:

- Some of these are people choosing not to have children. Childless couples are the most common family type, making up 41% of all family households.

- By the age of 40, one in 4 women remain childless.

- Others are households whose adult children have and left. Due to increased longevity, households will be in this “childless” state for longer. Stats NZ anticipates this household type will grow the most.

“Beanpole families” have also increased:

- Beanpole families are families containing several generations, with low numbers in each generation, living in a single household. They are therefore “tall and narrow”, like a beanpole.

- Thanks to increased longevity, beanpole families have also increased (more years of shared lives over generations).

Regions vs the centres

Since the 1900s, the New Zealand population has been moving north, towards Auckland:

- In the 1860s and 1870s, around two-thirds of the population (minus Māori, because of the census issues outlined above) was in the South Island during the gold rush in Central Otago. Dunedin was the largest city.

- In 1901, this reversed and the population has been moving steadily north.

- By the 2040s, about 80% of New Zealand’s population will be in the North Island. [Wow.] A large proportion of this will be in Auckland, Tauranga and Hamilton.

Increasing urbanisation is a global trend. The UK was the first country to have more than half of its population in cities by 1850.

City centres will grow

Centres expected to grow include Auckland, Hamilton, Tauranga, Wellington, Christchurch and Central Otago.

The growth is driven both by natural growth and immigration. City populations tend to be younger than in the regions, so they have a higher fertility rate.

Immigrants also prefer to move to cities rather than regions. For example, Christchurch has had a significant influx of migrant workers from Ireland and the Philippines to help with its rebuild following the 2010 and 2011 earthquakes. As a result, the ethnic composition of Christchurch, which has traditionally been dominated by European settlers and Pākehā, has started to change.

Some countries, like Canada, Australia and Japan, make efforts to direct their immigrants away from their main centres to their regions. New Zealand may be able to learn from their experiences.

The regions will face population stagnation or decline

Starting about now, 56 out of New Zealand’s 67 territorial authorities will experience population stagnation or decline, starting about now. Technically there was growth in all 16 regions (except Westland) in 2019. However, we should look at what happens within regions. Larger regional centres tend to grow but smaller towns don’t. For example, Central Otago and Queenstown grew by 3.9% and 3.7% respectively in the 2018-19 period. But growth in Clutha (0.8%) and Dunedin (1.0%) was much lower.

Absolute numbers are also important here. Otago’s growth is quite high in percentage terms, but is only 4,700 in absolute terms (comparable to Northland, at 4,000). Whereas Auckland’s growth in absolute terms averaged 25,100 between 2013 to 2018.

As communities shrink in size, they often lose services like health and education because there isn’t enough demand or revenue to pay for them. Recruiting GPs for rural areas and small towns is also challenging. This creates a vicious cycle that causes more people to leave (or not come in the first place). For example, Tuturumuri School near Martinborough closed in 2019 after operating for 97 years. At its peak in the late 1970s, it had 54 students. By 2019, they only had 7 at the start of the school year – and this later dropped to 2 during the year.

This is not just a problem in New Zealand. In Spain for example, more than 1500 settlements were abandoned as populations declined so much that it was no longer feasible to have a local village.

Populations in the regions tend to be older

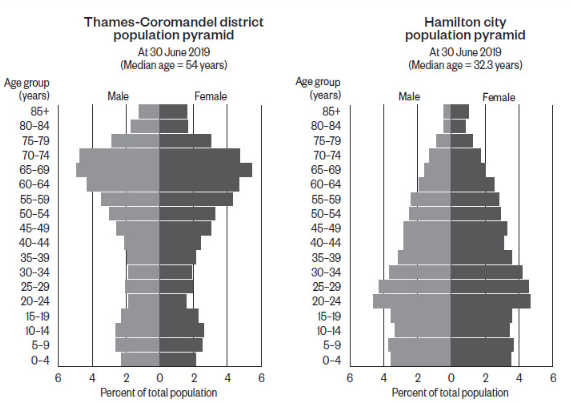

The median age and population pyramid of an area can tell you a lot about whether it’s facing population stagnation or decline. For example, Hamilton’s median age is the youngest at only 32.3. Wellington, Queenstown-Lakes and Dunedin have similarly young profiles, with young adults moving there to study and work.

Thames-Coromandel has the oldest median age at 54. As shown in the picture below, Thames-Coromandel’s population looks more like a cross than a pyramid, with the biggest age cluster in the 64-74 range.

Thames-Coromandel, Buller and Kāpiti-Coast all have more deaths than births. Similarly, Horowhenua, Masterton, South Wairarapa, Timaru, Waitaki and Gore have had zero natural increase in recent years (i.e. births equalling deaths).

Almost 30% of the population are over 65 in regions like Thames-Coromandel, Kāpiti and Horowhenua. Whereas the proportion of over-65s in Auckland, Wellington, Porirua and Queenstown-Lakes is only around 10%.

Regions are (generally) not willing to face up to their stagnation or decline

Spoonley talks about how, in Rebooting the Regions, he tried to draw attention to the fact that most regions in New Zealand would experience social and economic constraints as their population stagnated or declined. The book also offered policy suggestions for addressing such decline.

However, there was little enthusiasm for acknowledging the possibility of such decline, or for engaging with policy responses to it. Local politicians felt very uncomfortable with the idea – they were more used to planning for growth than for decline. Instead of accepting decline, they try to plan for “revitalisation”. But while there have been many economic growth initiatives aimed at boosting the regions, their effectiveness is questionable. Often such programmes overlook the demographic challenges involved.

Regions were also sometimes reluctant to consider being more proactive about attracting immigrants to counter the natural ageing of their populations. There are some exceptions, though.

- For example, in Ashburton, employers like ANSCO Foods and Silver Fern Farms realised they needed workers for their food-processing facilities. They began to recruit immigrants, often from the Pacific, later from the Philippines. Local council, community organisations and churches also helped develop the town’s social infrastructure. Immigrants and their families have been able to integrate into the local community and revitalise it.

- Gore and Oamaru have similarly been changed by immigrants, though they haven’t been as proactive as Ashburton in recruiting them.

Auckland

In many ways, Auckland will be quite different to anywhere else in New Zealand – it will be like another country. This phenomenon of an increasing divide between the largest cities and smaller cities and towns is common in many developed countries.

Auckland is growing faster

Auckland’s population is increasing – in both relative and absolute terms:

- Auckland has about a third of the country’s population today. This may rise to 40% by the 2030s unless there are major policy shifts. Spoonley points out that differs from the rest of the developed world – between 2015 and 2025, the populations of large cities is expected to decline by 17% as population growth slows.

- Auckland is almost 4 times larger than the next most populous cities (Christchurch or Wellington, depending on how the city is defined).

- Overall the city is growing at 1.5%, below the national rate of 1.6%. [How can that be? If Auckland’s growth rate is less than the national rate, how will its proportion of the population rise from a third to 40%? And if natural growth in Auckland is higher than average (because the population is younger) and growth from immigration is also higher than average (because immigrants prefer to go there), it’s hard to see how the city’s growth rate is less than the national rate. I suppose there is a net loss through internal migration (see below), but Spoonley doesn’t seem to think it’s that significant. There’s another part of the book where Spoonley says the city was growing at 2% annually after the GFC – but he doesn’t say how long after the GFC. So I don’t know what’s happening there.]

- Growth is mostly in the peri-urban areas. There’s less growth in the inner suburbs is lower, since they’re pretty much at capacity.

There is, however, a net internal migration loss from Auckland to other cities and regions:

- Auckland used to have a net internal migration gain, but after 2000 there have been net losses.

- This trend has picked up pace in recent years, but the media sometimes exaggerates it. The internal migration loss is more than offset by the migration gains and natural increase – for every departure there are around 5 arrivals.

- The types of people leaving Auckland are different to those moving to Auckland. Auckland is more likely to gain young adults (20-24 years old) moving for work or study. They also couple up, have children, etc – adding to the fertility of Auckland. It tends to lose young families and retirees.

It is also more diverse

In 2015, the World Migration Report ranked Auckland as the 4th most diverse city globally in terms of its proportion of migrants (behind Dubai, Brussels and Toronto, and alongside Sydney).

Its growth is mainly driven by immigration, particularly after the GFC:

- The city grew at more than 2% annually, and about two-thirds of this was from immigration. (There is still a decent amount of natural growth, though, as the city is one of the youngest in New Zealand.)

- Temporary migrants in particular are common – many of these are international students on study visas. A lot of these go on to transition to permanent residence.

- In the 2018 census, 41.6% of Aucklanders had been born in another country. 60% were either first- or second- generation immigrants.

- Due to ongoing immigration from Asia, combined with births to Asian mothers in New Zealand, the fastest-growing ethnic communities are Asian. In the 12 years from 2001 to 2013, for New Zealand generally, Europeans grew by 9%; Māori grew by 15%; Pasifika grew by 24%, and Asians grew by 49%.

Minority representation at local government is increasing:

- In 2013, Asians made up 23% of the city’s population but only 1% of local board representatives; Pasifika were 14% of the population but only 6% of representatives; Māori were 11% of the population but only 4% of the representatives.

- By 2019, however, more minority ethnic representatives were elected than ever before. [Would have been good to have percentages here as for 2013. It sounds like “than ever before” could have just been a low bar.]

But Auckland faces infrastructure pressures

Like many growing cities in developed countries, Auckland is not building houses fast enough to accommodate population growth, making houses more expensive than they should be.

Auckland’s population growth and age profile also puts pressure on the education system. 12 new schools will need to be built through to the late-2020s, mostly in the peri-urban fringe.

Ageing

The New New Zealand spends a lot of time discussing the challenges ahead as an increasing proportion of the population (the baby boomers) reaches the age of 65. However, Spoonley is careful to point out that we should also remember the upsides of this. The challenges are caused by health improvements, which have benefited many people.

Old people are becoming a bigger proportion of the population

Globally, more and more countries are becoming “aged societies”, with over-65s making up at least 20% of the population:

- Germany, Japan and Italy have been aged societies for a while. In Japan, 28% of the population is over 65, and this is expected to increase to one-third by 2050.

- The Netherlands, Sweden, Finland Greece and France will become aged societies soon.

- New Zealand is relatively far back in the queue, alongside the US, UK, Canada and Spain. New Zealand is expected to become an “aged society” in the late 2020s or early 2030s. But compare this to 1900 or 1966, when only 4% or 8% (respectively) of New Zealand’s population was over 65.

- These demographic changes have begun in high-income countries, but will expand to medium- and low-income countries too. For example, in 1987, over-65s made up just 4.2% of China’s population. By mid-2020s, they will be 14% and increasing.

The proportion of the population over 80 (“old old people”) will also grow. (This is significant because over-80s tend to require more long-term care):

- The OECD average is expected to grow from 4% (in 2010) to 9.4% (in 2050). This figure could even reach 15% in some countries like Germany, Korea and Italy.

- In New Zealand, the percentage of over-80s is expected to reach just under 10% in 2050.

This trend towards “aged societies” is driven by several things:

- First, the baby boomer generation reaching retirement age.

- Australia, Canada and New Zealand all experienced baby booms in the mid-20th century. New Zealand’s baby boom was larger and more sustained than nearly every other high income country.

- The baby boomer began reaching the age of 65 in 2010. Around 26,000 reach this age annually. The numbers will increase to 30,000 through the 2020s.

- Secondly, increasing life expectancy.

- Mortality rates at specific ages are declining due to health advances. (Overall death rates may still be increasing simply because the number of old people has increased, though.)

- Back when the retirement age was set at 65, life expectancy was around 75. Today, the highest life expectancy in the OECD is Japan, at 83.7 – and this is rising.

- However, life expectancy varies depending on socioeconomic status and ethnicity. Māori and Pasifika have lower life expectancy on average.

- There are gender differences too. Females tend to live longer but are less likely to be financially prepared.

- Regional differences also persist. On average, Aucklanders live around 4 years longer than people in Gisborne.

- Lastly, declining fertility rates, as mentioned above.

Consequences for labour supply and services

As a result of the above, the dependency ratio is increasing:

- The dependency ratio is the ratio of dependents (e.g. children and retirees) to people in paid employment. [Spoonley actually gives the ratio the other way around. However, this is what Wikipedia says, and I think it’s more intuitive for a higher dependency ratio to indicate a greater proportion of dependents.]

- For most advanced countries, during the mid-late 20th century, the dependency ratio was around 1:4. By the mid-21st century, the ratio will increase to 1:2 for many of those countries (including New Zealand).

The ageing of society presents challenges for providing adequate services (e.g. healthcare, residential care, transport):

- Demand for aged care workers will increase as the working population shrinks (in relative terms). In the 1970s, New Zealand had 15 entrants to the labour market for every 10 exiting it. By the 2040s, there will be only 5 entrants for every 10 people exiting.

- A lot of healthcare and residential care services are provided by immigrants. Currently almost one-third of those in the aged care sector hold some form of visa.

Demands for long-term care will also increase:

- In 2006, the New Zealand government paid for 90% of long-term care costs.

- It’s expected that the expenditure required for long-term care will increase from 1.4% of New Zealand’s GDP (in 2006) to around 3.5%-4.3% of GDP by 2050. Some countries expect the costs of aged care could even reach 4-6% of GDP by the 2050s.

Pensions

Globally, there are concerns about the funding of pensions and retirement benefits:

- The OECD trend is to increase the eligibility age for retirement benefits, usually to 67. Australia’s age will be 67 by 2023, while Denmark’s will be 70 by 2040. However, reforms is slow and the increases in eligibility age are slower than the increases in life expectancy.

- The World Bank anticipates a major shortfall between what is available from pension funds and what people will need to live by mid-century. Spoonley thinks that in New Zealand, the tipping point will probably arrive in the 2030s.

This holds true for New Zealand also:

- New Zealand’s superannuation system is a “pay as you go” (PAYG) system. Gratton and Scott (2016) point out that, if a state pension is set at around 30-40% of income and there are 10 workers for every pensioner, a tax rate of 3-4% on the current worker pays the bill. [If the dependency ratio is 1:2, that suggests just 2 workers for every dependant. Dependants also include children, who don’t receive pensions, so let’s say that’s 4 workers for every pensioner. That would imply a tax rate of 7.5-10% on each worker. That’s quite a lot!]

- Between 25-40% of those currently approaching retirement have no retirement savings, and will struggle even with the relatively generous superannuation system.

- The cost of housing is also an issue. Currently, 70% of over-65s own their home without a mortgage, but this percentage drops sharply for those in their fifties. So there may be more retirees still paying off mortgages in the future.

Many over-65s are still in paid work:

- Around 21% of over-65s in New Zealand are still in paid work. This is relatively high – compare this to the US (18%), Australia (12%) and the UK (10%).

- People may choose to work beyond 65 because they cannot afford to retire. Others may choose to keep working because they enjoy their job. Employers may also provide incentives to retain them due to skills shortages.

- Spoonley points out there are concerns that a large older workforce may block the opportunities for younger generations.

Migration

It’s hard to forecast population growth accurately. In 2004, people estimated New Zealand would reach 5 million people by 2050. That figure was actually reached in 2020.

New Zealanders tend to be extremely mobile:

- By the 2018 census, over a quarter (27.4%) of New Zealand’s population had been born in another country. This is similar to the proportion in Australia and Canada, but is high by OECD standards. For example, Germany, Britain, the US, France and Italy’s proportions range between 10% to 15%. [This surprised me, particularly for the European countries.]

- Around half had lived somewhere else (including elsewhere in New Zealand) in the last 5 years (in the 2006 and 2013 census).

Emigration

New Zealand has one of the largest diasporas in proportion to the size of the country:

- It’s estimated around one million New Zealand citizens and their children live outside New Zealand. (Note, however, that estimates vary as counting a diaspora is tricky.)

- The average diaspora size of OECD countries is about 4.1% of the total population. New Zealand’s is at 15%, similar to Ireland and Portugal. (Australia’s is only 3%.)

There are different types of diasporas: victim diasporas (e.g. Jews); imperial diasporas (e.g. the British); labour diasporas (e.g. Indians); and trade diasporas (e.g. Chinese throughout southeast Asia). New Zealand’s is an example of a “gold collar” diasporas – migration of the highly-skilled.

New Zealand doesn’t make much effort to engage with its diaspora. One notable exception is KEA, which seeks to identify and network with members of its diaspora. KEA is supported by New Zealand Trade and Enterprise. Some countries like the Philippines, Israel and Canada see their diasporas as part of their national communities. They take much more proactive approaches towards managing them.

There are interesting questions about the extent to which diaspora should have a say in the politics and policies of their homeland. Interests of homelands and diaspora are rarely identical.

New Zealanders in Australia

Most of New Zealand’s diaspora is in Australia – around 60%. There are more New Zealanders in Australia than vice versa. [Spoonley notes that in 1981, there were about 176,000 New Zealand-born residents in Australia and about 54,000 Australian-born residents in New Zealand. He then points out the numbers in Australia have since increased. By 2015, there were around 650,000 New Zealand citizens in Australia. Unhelpfully, however, he does not indicate how many Australian citizens were in New Zealand at the same time.]

Emigration to Australia reached peaks in the 1990s and again in the 2010-12 period. During these periods, Australia’s economy and labour market were strong relative to New Zealand’s. These peaks led to “brain drain” concerns. Some argued, however, that it was more of a “brain exchange” as the loss of skilled migrants to Australia was offset by the arrival of skilled immigrants.

In 1973, New Zealand and Australia signed the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement (TTTA), which allowed citizens to live and work in either country without a permit. However, Australia has made unilateral changes to it since, cutting back on the rights of New Zealanders in Australia:

- For example, in 1994, New Zealanders had to enter under a “Special Category Visa”. In 2000, such visa holders were denied access to welfare benefits for 2 years.

- In 2001, New Zealanders’ rights were further curtailed as eligibility for various benefits and student loans was reduced. New Zealanders also have to contribute to the National Disability Insurance Scheme, but cannot benefit from it (without becoming an Australian citizen, which has also been made harder).

- New Zealand, in contrast, has continued to extend all rights originally agreed under the TTTA to Australians.

One reason for Australia’s treatment of New Zealanders seems to be a concern that New Zealand migration rules are less strict than Australia’s. As such, people worried that New Zealand provided a “back door” to Australia for migrants from the Pacific. Another reason may be that people in Australia think immigration has been too high (in general, not necessarily from New Zealand), and the population has grown too quickly. There’s also been a tendency in Australia to highlight the importance of “Australian values”.

Immigration

New Zealand was built on immigration, much like Canada and Australia. All three countries developed as a result of British colonialism. British migrants, values and institutions were influential in all of them. These three countries also started welcoming Asian migrants since the second half the 20th century. As a result, all three are now some of the most super-diverse countries globally.

While there are some concerns and anxiety about immigration in all three countries today, it’s relatively mild compared to the demonisation of immigrants in the US and most of Europe. Spoonley thinks this is because Canada, Australia and New Zealand all operate points-based immigration systems, which mean that most migrants are skilled and well-educated and settle in well.

By 2019, population growth in New Zealand was driven more by immigration (two-thirds) than by natural growth (one-third).

History of New Zealand’s immigration system

For most of New Zealand’s history, the immigration system preferred immigrants from certain countries (e.g. UK) and discriminated against groups from other sources (e.g. Asians, Dalmatians, and Jews).

Two key changes occurred in the 1960s and 1970s:

- The first was the UK joining the European Economic Community. From 1974, UK citizens had to apply for a permit to migrate to New Zealand.

- The second was the increase in immigration from the Pacific Islands, due to New Zealand’s high demand for labour. When New Zealand’s high labour demands eased, a backlash against immigration led to deportations and restrictions in the 1970s and 1980s. The backlash was racist and highly politicised. Most “overstayers” were from Europe and the US, but it was Pasifika who were targeted (including even those who were actually New Zealand citizens). By 1990, more Pasifika were born in New Zealand than had migrated from the Pacific.

In 1986, the source country preference was replaced by a points system. The points system did not care about the origins of immigration applicants. The points system was further refined in the early 2000s, and provides the framework of the current system.

The immigration system today

New Zealand’s points-based system is usually called “merit-based”. In contrast, the US system is “demand-driven” as it’s led by employers. However, the New Zealand system also places a lot of weight on job offers, so it’s more accurate to say it is both merit-based and demand-driven.

More recently, temporary visas – both temporary work and study – have increased.

- There are currently over 200,000 temporary migrants each year.

- Temporary visas are valid for up to 12 months, but many temporary visa holders transition to became permanent residents.

- By 2011-12, more than 80% of those approved for residence previously held a temporary visa.

High levels of immigration post-2013

After 2013, New Zealand experience a period of unusually high net migration – both permanent and temporary migrants.

- There is no evidence of net migration gains exceeding 10,000 per year for more than a couple years in most of the historical record. But by 2019, total net migration exceeded 55,400.

- In 2019, net migration was 11.4 per 1,000 people (and this was after the Labour government had reduced numbers by 18,000 from the all-time high in 2017). In contrast, the US’s net migration was only 3 per 1,000 people.

Economic effects of immigration

Immigration is an important source of skills and labour, and is a major contributor to economic growth. There is a lot of international literature looking at how immigrants affect domestic workers’ jobs and wages.

In the US, there is evidence that immigrants positively contribute to the economy – they are twice as likely to start a company and three times more likely to patent an idea. This is despite the fact that the US system is not really skill-based. The US only grants 15% of green cards based on the applicant’s skills. In New Zealand and Australia, it’s around 60-70%.

In 2014, Julie Fry published a Treasury working paper following a comprehensive review of the evidence. She noted that the balance of evidence suggests that past immigration has, at times, had significant net benefits, but over the past couple of decades, the benefits are likely to have been modest. Fry concluded that immigration policy needed to be more closely tailored to the economy’s ability to adjust to population increases.

Fry and others agree that immigrants do not have a significant negative impact on local workers’ jobs or wages. They also agree that the impacts of immigration are largely positive. However, Spoonley notes that Michael Reddell, for example, has disputed these findings and argues that there are negative consequences from immigration.

Fry’s argument is largely that there isn’t really evidence of significant impact either way – whether positive or negative. However, part of the reason for this is that there’s a long lag between arrival and impact, so it’s hard to establish causality.

Social attitudes towards immigration

Migrants who are visibly and culturally different are most likely to experience negative reactions from New Zealanders. There were moral panics in the 1970s (in response to Pasifika immigrants) and 1990s (Asian immigrants) that demonised migrants.

Laws also reflect social attitudes. Starting with a poll tax in 1881, New Zealand has passed 33 pieces of legislation seeking to restrict the Chinese (and other) immigration, or to deny them rights available to other New Zealanders (e.g. pensions).

Today, most New Zealanders are more welcoming towards immigrants, but attitudes still differ depending on their source countries.

- In 2016, MBIE found that over half of New Zealanders surveyed were generally positive about immigrants. However, positive responses were most likely for immigrants from Australia and the UK (average rating 7.0 and 7.1 out of 10), and immigrants from India and China received lower ratings (5.5 and 5.4).

- The reasons for negative responses were mostly concerns around weakening of New Zealand culture and increase in crime. [I’d be willing to bet that average crime rates among Indian and Chinese immigrants are lower than crime rates for locals, though.]

Immigration is highly politicised in many other countries. Anti-immigrant sentiments don’t seem to be that strong in New Zealand:

- Even during the 2013-2018 period, where immigration exceeded anything in New Zealand’s history, backlash was still relatively mild. There weren’t major clashes or the re-emergence of a moral panic.

- Before the 2017 election, only 8% of those surveyed indicated that immigration was the issue most likely to affect their vote in the election. 31% were more concerned about the economy.

- Spoonley suggests that the reason is because most immigrants to New Zealand come on the skilled migrant category. They therefore tend to be better educated, have capital, and have relevant work experience. Spoonley thinks the “pick and choose” system tends to produce better settlement outcomes.

- Another interesting point is that New Zealand has a relatively relaxed attitude to citizenship. In most countries, immigrants don’t become officially recognised as a member of that country until they obtain citizenship. Whereas in New Zealand, permanent residents have most of the same rights as citizens, and there’s little expectation that they become citizens.

Boomers

Intragenerational differences are often more important than intergenerational ones. For example, a baby boomer Māori in New Zealand may have had very different opportunities and experiences from a baby boomer Pākehā.

However, there is evidence to suggest there are very different life outcomes depending on when you were born (and therefore when you left schooling or entered the labour market).

- In 2019, Bernard Hickey wrote that 1984 was a key year. Those born after 1984 are the “baby bust” generation, losing out relative to those born in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

- In the UK, it’s estimated that those born between 1956-1961 received 118% of what they paid in tax from the welfare state. But those born between 1971-1976 received only 95%. [The reference is to this Guardian article, but I can’t find that claim in there. The 118% figure seems to be from this book review instead (which the above article refers to), but I can’t find the 95% figure.]

The main ways in which boomers benefited compared to those in later generations involve education, housing and the job market.

Educational costs

There was a massive expansion of university education in the late 1960s and 1970s. Many more boomers went to university than in previous generations. However, the proportion was still much lower than today.

- In 1969, around 20% of secondary school leavers went on to university or teachers’ training college.

- In 2017, 61.2% of secondary school leavers went on to tertiary education.

The big change that happened globally was transferring part of the cost of tertiary education to students around the 1990s. In New Zealand, students had to pay fees in the 1970s and 1980s as well, but these were nominal.

Housing market

[The key point here is just that it was a lot easier for boomers to buy a house than for millennials. There’s nothing in this chapter that is really noteworthy.]

Spoonley writes:

“Changes to government policy through the 1980s and 1990s, combined with labour market changes, had a big impact on the levels of home ownership in New Zealand.”

He then goes on to compare the homeownership rates for the 15-40 age group in 2001 (35.3%) and in 2013 (22.1%). Spoonley also compares the overall rate of homeownership in the 1990s (74%) to 2018 (64.5%). **[Complete non-sequitur. Spoonley is asserting that it was changes to government policy in the 1980s and 1990s that impacted the levels of home ownership in New Zealand. Why then does he only produce statistics from the 1990s onwards? He also hasn’t suggested *which* government policies might be to blame.]

Job market

Jobs were relatively easy to get in the 1950s and 1960s. This changed in the 1970s, as levels of unemployment and underemployment rose. Spoonley say, “Even so, nominal wages … grew by 300 per cent during the 1970s”. [Why on earth do nominal wages matter at all? He doesn’t even explain that inflation was very high in the 1970s, which seems like a glaring omission.]

Spoonley asserts that since the 1990s, contract and part-time work has risen steadily thanks to changes to legislation which individualised employment contracts. In the growing “gig” economy, jobs were either low-paid or precarious. [No reference is provided. It would have been interesting to see how the unemployment rate changed as the “gig economy” rose. ]

Millennials entered the labour market during the GFC. Those who enter the labour market during a downturn usually take a long time to get up to the same levels of income (compared to those who entered outside of a downturn), if they ever do.

Other Interesting Points

- Currently, 250 million people live in a country other than their birth country. [This is lower than I thought. It’s only 3% of the world’s 7.7 billion population.]

- Census questions change over time. Until 1971, the New Zealand census asked how many chickens each household kept.

- It was marketers who started labelling generations (baby boomers, Gen X, millennials, etc) to understand the consumption patterns of different cohorts.

- A NZHerald article pointed out that, of the MPs in Parliament in 2019, there were 37 baby boomers, 66 Gen Xers, 17 millennials, and only 1 member of the Silent Generation (Winston Peters). Surprisingly, Labour was the least “generationally diverse”, with baby boomers still making up a lot of its MPs.

My Thoughts

The New New Zealand tackles an interesting, important and neglected topic. I feel like I have a better idea of the demographic challenges New Zealand faces in the coming years. Spoonley is light on policy prescriptions, though. Overall, his message is that “we need to have informed national discussions about this”, which seems sensible enough and fairly unobjectionable.

Unfortunately, Spoonley did not impress me as a writer. He gives us plenty of statistics, without providing appropriate context and suggesting what conclusions we should draw from them. For example, he writes:

“In 1990, there were 24,000 over the age of 65 in paid work in New Zealand. In 2014, it was 127,000 – and growing.”

Absolute numbers are not very useful here. How did the numbers of over-65s in paid work compare to the total numbers of over-65s? That is, how much of the increase is due to an increase in the tendency of over-65s to continue working, rather than just the general increase in over-65s?

Instead of addressing this, Spoonley then adds:

“Between 1996 and 2016, the number of over-65s in paid work grew by a staggering 488 per cent, compared to a seven per cent rise in the number of 15-24-year-olds in employment.”

Why is he comparing the growth in numbers of over-65s in paid work with the growth in numbers of young people in employment? Again, a more useful comparison would have been to compare it to the growth in number of over-65s in general.

At the same time, Spoonley doesn’t always provide enough statistics, either. A lot of the citations for his statistics are secondary reports, newspaper or magazine articles. He’s relied on other authors to pick the “relevant” statistics, rather than going to first-hand sources like StatsNZ himself. This feels, well, lazy. I don’t feel confident Spoonley has checked the statistics himself. In some cases, the figures he cites are out of date, when more recent figures were probably available, and would have been more relevant.

Spoonley admits he’s not a demographer, but rather “a sociologist who dabbles in demography”. That may explain the completely unnecessary “OK Boomer” chapter, which was easily the weakest part of The New New Zealand. It had little to do with demography and much more to do with sociology. In his “Acknowledgements” section, Spoonley thanks his two sons “who continually remind me that baby boomers – like me – have had a lot of support throughout their lives, a level of support that is simply not available to them”. It seems like he wrote the chapter primarily for his sons’ benefit.

The chapter has little relevance to the rest of the book, apart from pointing out that there are intergenerational tensions which may affect the politics around some policies (e.g. superannuation). I mean, sure, but anyone who’s read a newspaper in the last 10 years already knows this – it hardly merited an entire chapter. The “OK Boomer” just detracts from the rest of the book. Here more than anywhere else, Spoonley seemed to rely excessively on secondary news articles and opinion pieces rather than on hard evidence.

Overall, I think I learned something from The New New Zealand. I am a bit dubious about how robust some of Spoonley’s assertions are, but the key takeaways seem plausible and sensible enough. Just ignore that “OK boomer” chapter.

Buy The New New Zealand at: Amazon | Kobo <– These are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase. I’d be grateful if you considered supporting the site in this way! 🙂

Have you read this book? Think I’m being too harsh on Spoonley? Let me know what you think in the comments below.

If you enjoyed this summary of The New New Zealand, you might also like: